University responds to student safety concerns

January 27, 2017

At one point senior Kiley Boland felt like she was getting crime alert emails as often as she was Zara spam.

Like other universities, Wake Forest experiences crime, but this semester a sense of safety was punctured after what seemed like an increased series of offenses. In the midst of heightened student concerns, a vacuum for worried dialogue was established, but not necessarily justified.

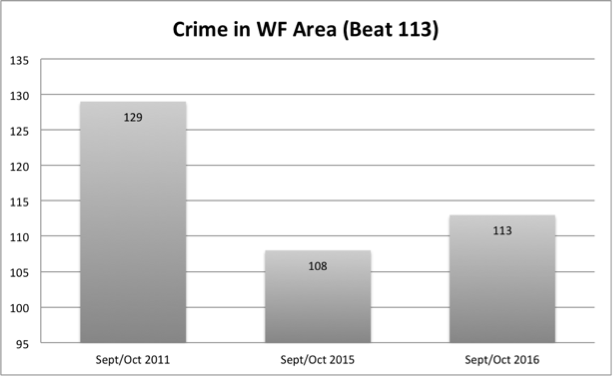

Between the months of September and October of 2016, only five more incidents occurred compared to last year.

Nate French, who graduated from Wake Forest in 1993 and currently serves as director of the Magnolia Scholars Program and is a member of the office of the dean of Wake Forest College, attested to a tangible sense of fear that he believes was heighted by the political context of this year.

“Wake Forest has always been a relatively safe campus,” French said. “When I was a student, Wake was the absolute safest place ever and no one talked about crime. But I’ve heard students talk more about safety this year. And that’s a big difference.”

Background

On Sept. 9, 2016 three senior students were held at gunpoint in their off campus home. It wasn’t long before the community was shocked again. In separate occasions on the night of Oct. 15, three male students were physically assaulted and verbally threatened on their walks from University Drive to campus.

On Oct. 22, a male law student and female friend were abducted by an armed man and forced to withdraw cash from an ATM before being released.

And on Oct. 30, a female student was struck in the face by two unknown individuals on Hearn Plaza.

Unnerved and overwhelmed, students searched for explanations.

“I hope that what’s happened recently is a heads-up to the administration and campus safety,” said one male student who was assaulted. “We have a nice, beautiful campus, but we are also in what some might call a ‘tough’ neighborhood.”

Another student, senior Will Robinson, shared his opinion.

“Winston-Salem is known for its wealth disparities, so I think a lot of people see affluent kids and think it’s an opportunity to rob them,” Robinson said. “But I don’t understand why kids are just getting punched.”

Response to Crime

In an effort to ease negative perceptions of constant crime affecting Wake Forest, the university reacted quickly. The Wake Forest University Police Department (WFPD) contracted the Winston-Salem Police Department (WSPD) to conduct 24-hour patrolling in neighborhoods inhabited by Wake Forest students.

WFPD Major Derri Stormer isn’t shocked by the crime, but she said that this year seemed unique.

“In the past it’s been so spaced out that I don’t think it was a ripple in people’s minds,” Stormer said. “But crime does happen, and you can do as much as you want. Even if we had 1,000 cops in the area, that doesn’t mean crime is just going to go away.”

Although some Wake Forest students felt like there was more crime this year than last year, numbers indicate otherwise. For the past five years, crime hasn’t fluctuated significantly.

For example, in 2015 there were 665 part 1 crimes in beat 113, the Wake Forest University territory and the areas just beyond campus. Part 1 offenses include homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft and arson. In 2016, between Jan 1. 2016, and Dec. 2, 2016, there were 560 offenses.

During September and October of 2016, there were 113 part 1 offenses. In 2015 there were a total of 108 offenses.

Conversation Started

While statistics show a relatively steady trend in crime around the Wake Forest area, something triggered conversations.

So, what exactly changed? If crime records prove that there is little change in numbers, then why do Wake Forest students seem more worried about their safety this year?

French suggests that the combination of email alerts, coupled with this year’s presidential election, reshaped dialogues on campus. It’s likely that the normalization of radicalized discourse, which highlighted crime, provoked people to find excuses for why things, like crime, were happening.

“Maybe communication is better,” French said. “But that has a double effect. On one hand it’s better because it’s providing notice, but on the other hand it’s providing information for people to say, ‘Oh my God, I’ve gotten three alerts in the past month.’”

Wake Forest senior, Isabel Penrose doesn’t discount the crimes, but agreed that the rhetoric used this year probably influenced the way people viewed the world outside Wake Forest’s bubble.

“I think the severity of the crimes, like people I know being held at gunpoint and being kidnapped, blew-up the amount of crime that was actually happening,” Penrose said. “On top of that, I think the hateful rhetoric largely spewed by the Trump campaign created an atmosphere of fearfulness and uncertainty.”

In an effort to better understand the idea of perceived fear, consider “The Cultivation Theory,” which connects consumption of media messages to the belief that the messages are true. In turn, if people are exposed to the idea of violence, they are more likely to think the world is more dangerous than it is. As a result, whom to place the blame on became subjective.

Even Javar Jones, a senior and Winston-Salem local, took the side of the greater Wake Forest student perception.

“The stereotype goes that Wake Forest has a bunch of well-to-do people,” Jones said. “And members of the community decide to take advantage of that.”

Some Wake Forest outsiders had a similar perspective.

Mike Gray, a student at Winston-Salem State University, gave his opinion for why he believes criminals may choose to target Wake Forest over WSSU.

“I mean we get robbed too, but I guess it’s just better pickings at Wake Forest,” Gray said. “If you’re going to break into something, you’re going to break into something that looks nice. That’s robbing 101.”

Digesting the Facts

According to the universities’ websites, Wake Forest’s undergraduate tuition amounts to roughly $49,000, while Winston-Salem State’s undergraduate tuition is $18,000. Of the nearly 5,500 students who attend WSSU, close to 90 percent receive financial aid. Meanwhile, only 30 percent of Wake Forest’s 4,800 students receive financial aid.

Maybe the pickings are better at Wake Forest. Numbers suggest that could be the case.

In 2015 there were 626 part 1 crimes in beat 211, the WSSU territory and the areas just beyond the university. Meanwhile, Wake Forest’s beat 113 had 665 part 1 crimes in 2015.

According to numbers, there is little base for students to feel less safe this year than they have previously. Albeit, the only explanation seems to be from dialogue that may have only resonated because of the radicalized context of this year’s discussions.

“We live in a post-truth society,” French said. “Where there are no facts and facts don’t matter.”