There was a time not long ago when you could not stream a pirated movie under the covers and when Google Art couldn’t produce for you a Degas more vivid than the painting itself. What I am referring to is the epoch of investment, a time when presence was integral to art.

You had to go to a theater to see a film and were forced to pay earned money to view a work of art in a museum. Shuffling and sweating alongside many others, you hoped to catch a half-lucid glimpse of the tiny, guarded masterpiece that has engrossed the world for centuries. Art was bound up in experience, and existed as a multi-faceted memory, not a summon from oblivion.

Culture has lapsed, as I have said many times. That culture — art, film, music — is so disposable that it ceases to leave the slightest imprint, and we have made it so. I notice it in myself. As I search for new music, a song’s first few seconds determine its viability. If it doesn’t meet my kitsch-quotient initially, I will click ahead to the chorus, give that a brief window, and then decide if the song is worth listening to in its fleshed-out form.

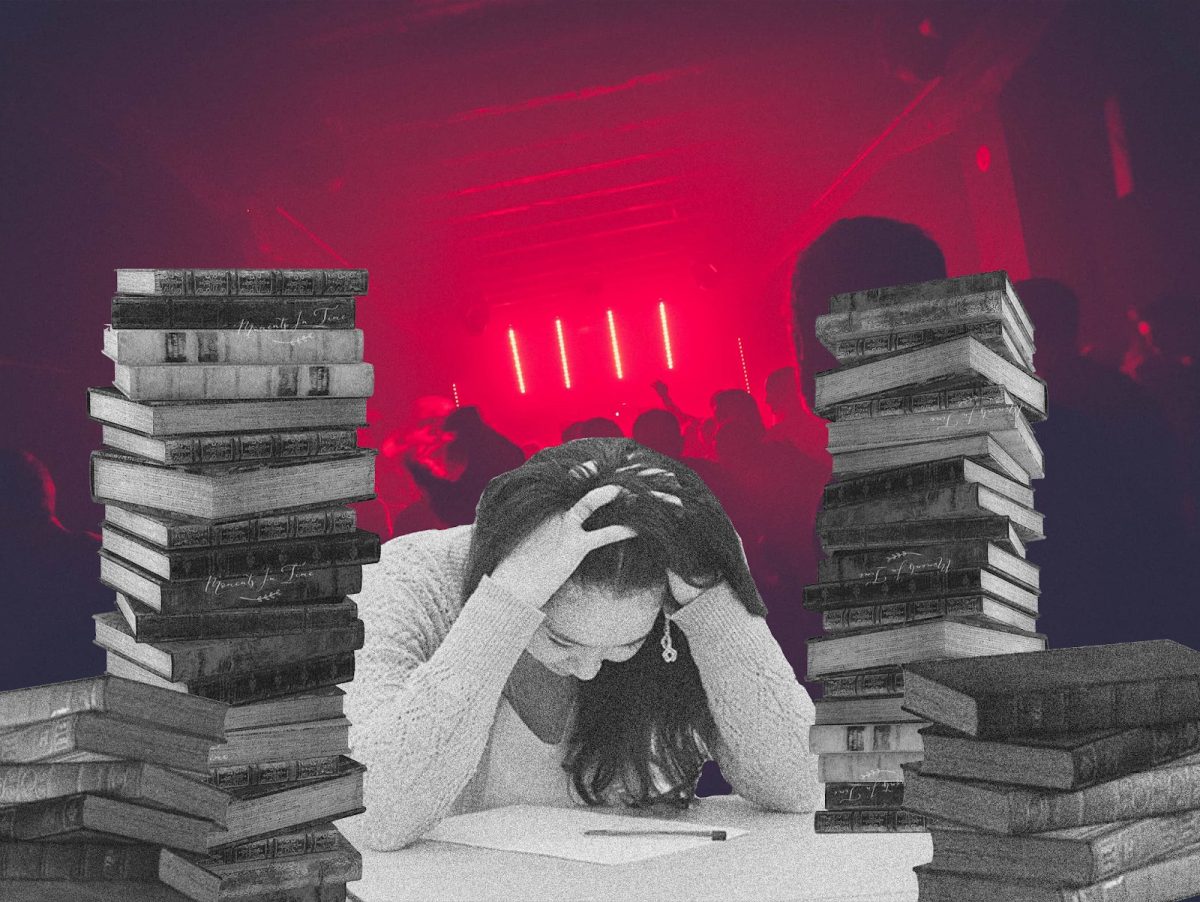

The age of intensely scrutinizing art — deliberating over an album, perusing a novel — is waning. There is so much prefatory material that the unknown work is hardly ever unknown, hardly ever an undigested experience.

“Going to buy the book, waiting in line to see the movie [and] purchasing the album,” Bret Easton Ellis says has become an anachronistic annoyance. A culture of impatience seems to knock such experiential ventures into oblivescence.

Our relationship with art is with an eye towards its proximity. Creations enter our consciousness already half-relinquished — threadbare and tangential. Art costs next to nothing to buy, even less to discard. To listen to an album of 10 or so songs, and to know that is all you have access to, would infuriate the modern mind. But, maybe, after the withdrawal of media methadone, the mind can settle into a fruitful address.

American musician Moby anecdotally recalls such an experience. He recounts, “I remember buying my first David Bowie record, and it didn’t make sense to me. But I had invested seven dollars in it, so I listened to it until it made sense to me. My assumption when I was listening to this David Bowie album, Lodger, was … ‘I don’t understand this. It’s my fault. He’s David Bowie … If I don’t get it there’s something wrong with me.’”

Today’s sentiment is not that we owe it to artists to work towards understanding their work, it is that they themselves need to be the clairvoyant creator. This is the systematic sterilization and distillation of the artistic sensibility that has bastardized much of the art we consume. The faulty notion levied by mass culture is that the problem is not us, it is them. Bad art has become synonymous with difficult art.

The state of art, for the most part, is a state of facile joys. Moby continues by articulating our scattered brains that view art as a flash in the pan: “your average 13-year-old or whomever gives a song five seconds. And why not? They just move on. Music, art [and] literature didn’t’ have as much competition when we were growing up. Now a fifteen-year-old kid has so many profoundly compelling things in his life … There’s so much competing, that how is that person ever going to sit down and lose themselves in a book … commit themselves to understanding a record that at first listen doesn’t make sense to them.”

The vague but insistent pulse of art-to-be-consumed is a full-brain ache. A sort of wispy, candied cloud hovers around us like a distracting sibling. To fully dispense one’s pittance of concentration on a single work of art is something we struggle to do, something most people do not wish to do. It takes a seemingly Herculean effort.

But if we try to live our lives skimming the surface of art, without any interest in what is really going on, what is the point? You hear all the time that people are so dissatisfied with their lives. Maybe it’s be