Though you enter The Adding Machine expecting to see a play about the perils of technology and the way it changes society and humanity, your general questioning about humanity after the play will certainly not be about technology, but instead will focus on mortality and whether being a good person even matters.

The plays opening and is reminiscent of Fahrenheit 451; it centers around an accountant by the name of Mr. Zero, played by sophmore Michael Littrell, who is replaced by an automated adding machine and is subsequently fired. After losing his job, Zero kills his boss and is put in prison. Doesn’t seem out of the ordinary, right? Think again. After Zero is put in prison the first act closes, the second opens, Zero is dead and all expectations are thrown to the wind.

The first act opens with Zero and his very pedantically dissatisfied wife Mrs. Zero, played by junior Anne-Peyton Brothers. The eerily choreographed coworkers Mr. and Mrs. One through Six are a great complement to the overall themes of the first act and the eerie, mechanical tone that pervades the entire act and play. The first act asks those expected questions about technology, and how technology affects us, but more important than these questions is the commentary on the modern society of the 20th century. Rice reveals his pessimistic views of the middle class of America during this time period through they ways Zero interacts with his wife and his coworkers and the racist, xenophobic and misogynistic views that these characters hold, causing an uneasy feeling of distance between the audience and the characters.

In the second act you are simply told that Zero is dead, when you were expecting some sort of scene with him in prison. While most likely a fault of the writing, it is confusing and gives an awkward feeling that you have missed something. This fault detracts from the overall themes and questions of the second act. The second act is truly a curveball from what I was expecting. If the first act is Fahrenheit 451, the second act is a bizarre quasi-mix of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Chicago and Great Expectations. Without it spoiling the sheer flabbergast that I experienced, asks broad questions about morality and represents a more postmodern view on the whole ideal of dying.

The best scene of the play is the last. It diverges from the rest of the play and is surprisingly refreshing compared to the heavy drama of the rest of the play. After facing the harsh realities of ideas of technology, the ephemerality of life and the insignificance of life, the playwright gives us a light-hearted view on the matter. While, of course, it still addresses the depressing main themes of the play, it does so with comedy. Despite the fact that his costume appears to be directly stolen off the back of Jimmy Buffett, Avery McClure as Lieutenant — not Captain — Charles, and his dynamic partnership with Charles Cicchino as Joe are splendid. Their synergistic relationship is easily the most memorable part of the play. While this may be due to their anachronistic dress and attitudes, nevertheless their seemingly alien (at least to Zero) scene is phenomenally acted.

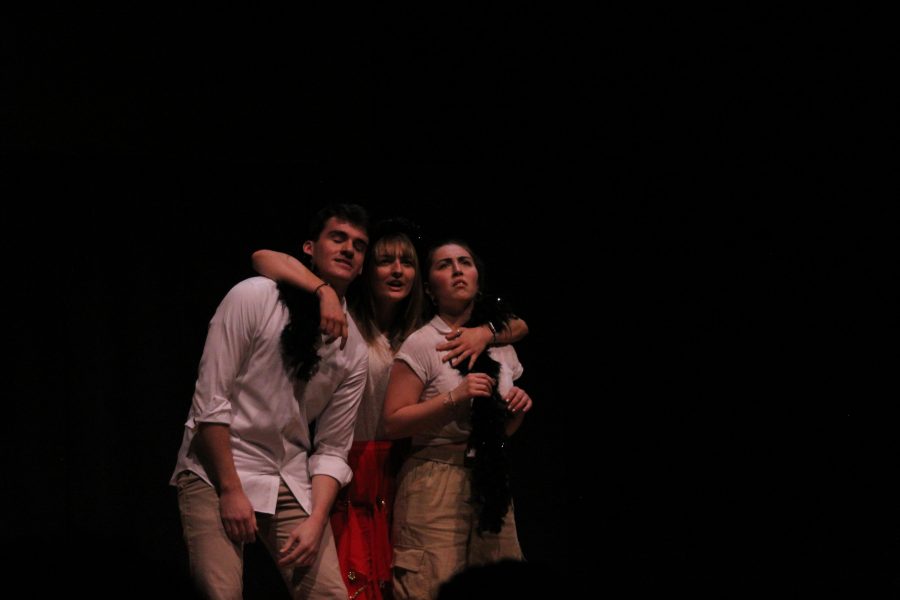

Overall, all of the actors approached their roles admirably. The choreographed movements within the bevy of numbered people was superb and dead-on, showing the commitment of the actors. Furthermore, the touches of comedy throughout shows the attention to detail on account of director Brook Davis. Precisely, the acting of Littrell as Mr. Zero contributes to our dislike of him, Littrell plays him with a rough and awkward personality. Littrell’s acting turns Zero into the perfect anti-hero that you relate to due to his immorality and imperfections. Additionally, the commendable synergy between sophmore Katy Milan, as Daisy, and Littrell is elegantly entertaining; both work well together to reveal both the relationship between the two, as well as the personalities and idiosyncrasies of both characters.

Moreover, the lighting and scenery is fantastically suited to the themes of the play. The multiple ways that the scenery is manipulated shows both the creativity of scenic designer senior Jyles Rodgers and the active role of the actors in all parts of the play. Specifically, the lighting of the first act helped the emphasize the character of Zero and his dramatic closing monologue. While the scenery is initially a bit confusing, as the overall themes come to light, it blends well with both scenes and really helps to push forth the non-realism thing they’ve got going on. It blends well with the initial tone of technology and mechanic, and then continues to blend in the second act. I also feel that the scenery adds something to the overall discussion of motif; it forces you to consider time alongside mortality, which I think is an effective addition to the overall comprehensive discussion.

Although the play is initially very confusing in its initial curveball of a second act, it grows on you. You exit the play with questions you did not expect to be asking yourself, and I think this is an exceedingly valuable quality in a piece of art. The play was sufficiently entertaining with the added quality of causing skepticism over every aspect of what you believe about morality, and life in general.