Student reminisces on nostalgic song, “Hunnybee”

Hunnybee is revisited through the lens of a student’s life and emotions in a pandemic

The Unkown Metal Orchestra is a psychedelic rock band from New Zealand that rose to popularity due to their distinctive electro-rock sound.

February 4, 2021

It’s hard to believe that The Unknown Mortal Orchestra’s most recently popularized song, “Hunnybee” came out a little over two years ago. It is a prescient encapsulation of pandemic-induced anxieties. Notions of separation, changing seasons, and distanced love in the song predict our present reality. I found myself turning to “Hunnybee” to translate my own feelings. It filled my old car, my childhood bedroom, my endless walks around the neighborhood. It imbued every aspect of my stationary life with a sense of looming. At the times I felt on the verge of bursting, “Hunnybee” coaxed me into an exploration of my own isolation.

Even when I play it now, the dissonance startles me, yet soon manages to totally envelope me in its dreamy world. It’s like the taste of something metallic in your mouth, but is it something foreign or your own blood? Your understanding of what you would normally taste suddenly clashes with this synthetic sensation; it’s an unnatural pleasure — one in which you attempt to define where you end and where what is unnatural begins. Just as UMO utilizes technology to warp the sound of an orchestra, there lies an intention in altering natural sound with synthetic technology. The mind must work to parse when one ends and the other begins.

The initial strings evoke despair. I always picture an old silent film in these beginning moments, some old movie star with dark eyes and darker eyebrows weeping. Then, at the height of her misery, a sharp cut to a title card. From this point on, the musical composition appears to be about constraint, squeezing the once drawn out strings into a bizarre summation of what they once were. This condensation releases into a musical explosion — a backbeat with some plucky guitar and lulling, dreamlike chimes that illuminate like light dancing off diamonds, periodic flashes of light that just as quickly disappear.

The mind, once dampened by the rainy strings in the beginning, now finds itself in a marvelous interim, this strange, slippery disco world before the lead singer Nielson upholsters the instruments with a voice.

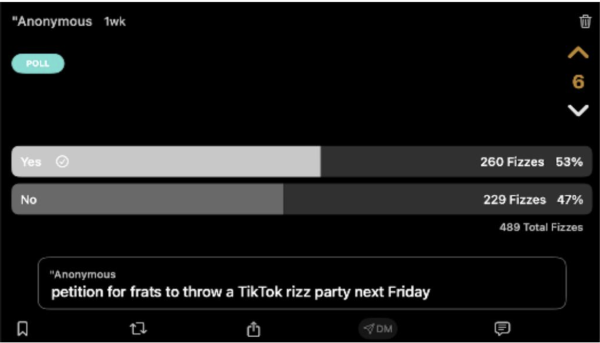

“Days are getting darker,” he breathes with a fuzzy voice. Indeed. Here, an eclipse sets a shadow upon it all, a day once sunny with life has led to a retreat indoors — from the position of contemplation rather than that of action. “Don’t be such a modern stranger,” he implores the subject of the song.

It makes me think. Does the way the pandemic asks us to live — introspective, compulsively concerned, paranoid — mimic the flavor of losing love? For, as Coleridge explains, “Life is thorny; and youth is vain; and to be wroth with the one we love doth work like madness in the brain.”

Perhaps what I initially perceived as prescience about the anxieties of the pandemic is actually an imagining of what it feels like to see love falling from your grasp. The emotions that this pandemic stirs up are a kind of alternate version of what it feels like to be in the midst of a failing relationship you so desperately wish to save. To have a madness in the brain — to see the world once laid before you rotting away, to be powerless to stop it, and to watch in dejection aimlessly searching until something strikes you in the way you also wish to strike the world.

Jorge Garcia • Aug 11, 2022 at 7:24 am

Thank you