‘1776’ seeks to update itself

A diverse cast and musical changes attempt to bring the musical into the modern era

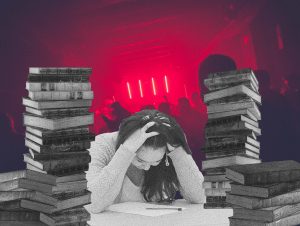

A diverse cast is one way show runners have attempted to update “1776.”

November 10, 2022

My journey to see the Broadway revival of the classic musical “1776” has been a long one. First, production was halted for more than two years by the pandemic; then, I was hampered by my inability to drop everything and fly to New York mid-semester. Finally, over fall break, I was able to see the revival.

While I chose not to read any reviews beforehand in order to avoid preconceived notions, my feelings after the show echoed that of most critics: more than a little mixed.

Set during the summer of 1776 in Philadelphia, the musical follows John Adams as he struggles to convince the Second Continental Congress to declare independence from England. “1776” originally debuted two years before the country’s patriotic bicentennial in 1969 and ran for over a thousand performances, closing in 1972. The musical has been referred to as the original “Hamilton”, and the latter actually references what are perhaps the former’s most recognizable lyrics in “The Adams Administration” when Alexander Hamilton commands Adams, the second president of the US at the time, to “sit down, John.”

This particular revival has attracted attention for its radical casting, which is race-blind and consists entirely of women, nonbinary and transgender actors. While race-blind productions of the show have been put on before, the latter casting choice is revolutionary, especially given that only two of the twenty-six roles in the original production were played by women.

Further controversy has been stirred from within the show. In a recent interview, actor Sarah Porkalob — who plays pro-slavery South Carolina delegate Edward Rutledge — criticized aspects of the production. Among other things, she claimed that there had been “harm done” to non-Black POC actors while the directors were conceptualizing a scene that reenacts a slave auction. Porkalobalso stated she is only giving the show “75%” of her potential. After receiving backlash from within the theater community and one of the musical’s co-directors, Porkalob apologized on Twitter for “the pain [she] caused [her] team.”

Taking into account the subject matter and historical context of the original release, it is safe to say that updating the musical to suit today’s political climate was always going to be a challenge.

While the casting decisions are the most immediately obvious update, they are far from the only ones. The consciously progressive musical has been peppered with updates right out of the gate.

In the opening two minutes, Crystal Lucas-Perry guides the cast as John Adams through a scene where they metaphorically and literally step into the heeled shoes of their characters, pull stockings up over street clothes and don gloriously vibrant dress coats. The cast’s diversity is immediately apparent, extending beyond race and queerness to encompass body and age diversity. Elizabeth A. Davis, who played Thomas Jefferson, is even visibly pregnant — particularly notable given how often pregnancy is concealed in cinematic and theatrical productions.

Regardless of whether the casting accomplishes anything on an artistic level, it succeeds in increasing the visibility of actors who have previously been barred from such roles. These actors also invite the audience to consider the faces not granted or consulted on the legal rights of groups discussed in the musical, creating a palpable situational irony. These factors alone make the casting decisions worthwhile.

The actors themselves and the chemistry between them are excellent. Patrena Murray brought the perfect mix of wit, cunning and charm to her role as Benjamin Franklin, and Shawna Hamic was delightfully effusive as Richard Henry Lee.

Allyson Kaye Daniel excellently plays Abigail Adams, one of the musical’s two female characters. In this updated revival, Abigail’s character reminds her husband to “remember the ladies,” quoting the historical Adams’s famous appeal to her husband to consider women’s rights in the nation’s forthcoming new code of laws. The quotation, far more recognizable today than during the original 1969 run, both acknowledges her womanhood and elevates her role as her husband’s key confidant — and correspondingly drew raucous applause from the crowd.

The same influence is not given to the other female character, Martha Jefferson, played by Erin LeCroy. In her single appearance, Martha is reduced to an unhinged, moaning mess, sexually excited by her husband’s violin playing. Constraints of the source material might never have allowed Martha ever to pass the Bechdel test, but this take feels particularly unsatisfying, being a missed opportunity to deepen and complicate the role women played during the time.

Martha’s single song, “He Plays the Violin,” also drew attention to how significantly the music has changed. Some of these overhauls are successful. Most are not. The scores have been so altered from the original’s orchestral pieces that they often no longer resemble the original musical at all, save for a few distinctive snatches of melody.

This often results in a song that simply sounds generic, or one where the crescendo is cut lamentably short in favor of an anticlimactic acapella. Sometimes the instrumentation overpowers the lyrics entirely, making them impossible to discern. Other times, the music is jarringly out of place, and genres are poorly blended, as was the case during “Momma Look Sharp,” where someone strumming a guitar made me feel like I was about to witness an old Western duel rather than hear a tragic ballad about a mother discovering that her son had been killed in battle.

The biggest narrative change of all, however, comes at the end in a final stark image that completely changes the tone of the play. The Declaration is successfully signed, and someone announces they’ll ring the Liberty Bell — but in this version, that never happens. Instead, the actors gather on stage facing the audience singing a haunting refrain from “Is Anybody There?” while the music dissolves into a nightmarish crescendo, and the backdrop peels away to reveal hundreds of barrels of rum lit in red. The imagery harkens back to an earlier nightmare sequence from the song “Molasses to Rum,” led by the character Edward Rutledge, who calls out the hypocrisy of abolitionist northerners who profited from their complicity in the slave trade.

Ultimately, this dramatic change suggests that the compromises made by the Continental Congress to achieve independence were not worth it — namely, striking the anti-slavery clause from the Declaration to win over the southern colonies. Liberty and political power were not intended for all, which is perhaps most directly referenced in an added scene where Jefferson recites the lines of the Declaration as his slave dresses him: As Jefferson discusses liberty, an uncomfortable, self-aware silence results. As the musical points out, slaves were excluded from the Continental Congress. They had no say in whether upholding the institution of slavery was an acceptable compromise for American independence, but they nevertheless suffered its consequences.

While the question of whether independence at any cost is justifiable certainly merits discussion, the musical leaves it unanswered. The tone of the ending seems at odds with some earlier narrative decisions, such as the fast-paced projection of images from America’s most notable political protests and human rights icons during the song “The Egg,” an optimistic intervention that suggests a long arc of revolution.

In the end, this iteration of “1776” is a musical that cannot decide what it wants to be in its struggle both to elevate and move past the constraints of its source material. While not a complete whitewash of history, the original “1776” is certainly dated today. The question of whether it is possible to bring the play fully into the modern era — or whether that should be done at all — remains unanswered. In this case, it feels like the clearer choice might have been to commission something new entirely.