Stepping into a musical time capsule

Reflecting on the American folk tradition through the lens of a local bluegrass band

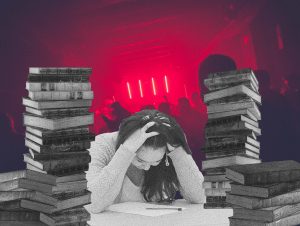

Russell Moore (center) performs with IIIrd Time Out.

January 18, 2023

After a couple of wrong turns off the dimly lit, two-lane blacktop, I finally came across my final destination. The nondescript, sheet-metal building was shrouded in darkness as I pulled into the gravel lot, accompanied by droves of other parked cars. Stepping inside, I was transported to another time. To my left was a man handing out the sorts of tickets you’d find at a high school sporting event or community raffle — $20 at the door, cash only. White tile lined the venue floor, paired with large wood paneling and illuminated with warm stringed lights. I took my seat in the sea of metal folding chairs, surrounded by a few hundred flannel-clad, boot-wearing, blue-collar concertgoers milling about. The concert hall itself breathed an air of familiarity, closely resembling your average church or community center — it felt as though it was a place I had already been.

People of all ages had come from miles around to see one of the biggest names in bluegrass, Russell Moore and his band IIIrd Tyme Out, kick off their 2023 tour. All attention turned toward the stage as the band opened their first show at the Fairview Ruritan Club with the “Pretty Little Girl From Galax,” a local favorite. Moore’s euphonious voice filled the air, accompanied by the antiquated sounds of Appalachia — a guitar, mandolin and fiddle.

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains just beyond the North Carolina border, the sleepy town of Galax, Va. is located just 60 miles from Wake Forest University. Galax is a growing locale known for its cultural ties to the music scene in the Blue Ridge. It has been dubbed the “World Capital of Old Time Mountain Music” thanks to the annual Galax Old Fiddlers’ Convention held there every August since 1935. The township has become a destination for musicians and spectators alike from around the world.

The Fairview Ruritan Club is a local civic club, dedicated to “community service through fellowship and goodwill.” The club frequently holds concerts featuring prominent figures in the Bluegrass music scene — Russell Moore and IIIrd Tyme Out are a great example; a band that has headlined the biggest bluegrass festivals and sold out shows in places like Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia. They have also won several International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) awards including seven Vocal Group of the Year titles. Moore himself has won six Male Vocalist of the Year awards — 2019 being his most recent — cementing his place in the Bluegrass community as a well respected and accoladed member. After the show, I was able to catch up with Moore to ask him a few questions about the genre itself.

“You get strong, really strong ties with Appalachia, you know, the music that was here way before recordings were done,” Moore said. “It’s mainly acoustic music. You don’t hear a lot of big drum sets and electric guitars…and in some senses, it is more challenging to play an acoustic instrument and get something across to somebody as opposed to a lot of just volume.”

Bluegrass developed during the 1940s, drawing elements from a mixture of Scottish music and blues, characterized by a faster tempo in conjunction with close-knit harmonies and high-pitched tenor. Pioneered by Bill Monroe, bluegrass quickly gained a foothold in the country-western genre, eventually evolving into its own unique category of music.

“ [Bill Monroe] experimented with other instruments,” Moore said. “When he got the combination of his mandolin, the guitar, banjo, fiddle and upright bass, that’s when the magic happened. He was influenced by a lot of different music growing up, even blues. He kind of just meshed all of that stuff together. You can really hear fractions of that in all bluegrass music.”

As I dug deeper into my buttery, $1 popcorn from the snack bar, Moore and IIIrd Tyme Out paid homage to “The Father of Bluegrass” by playing Bill Monroe’s “Old, Old House.” Then they moved on to new material. I sat in wonderment watching the quintet effortlessly strum beautiful melodies — all layered with the sound of Moore’s sweet voice. The crowd became increasingly involved as the night progressed, singing along and stirring in their seats to the rhythm of the music. A warm and jovial atmosphere filled the space. The chemistry on stage contributed to the lightheartedness of the evening — they were incredibly passionate about playing and extremely grateful for the crowd that night.

After a brief intermission, the second half of the show saw the band exclusively play songs requested by the crowd. One example was the band’s beautiful bluegrass rendition of John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads.” They played several more requests before calling it a night.

After profusely apologizing for not being able to get to everyone’s song requests, Moore and IIIrd Tyme Out departed the stage to a standing ovation. They had just completed their first performance of the year, an experience that felt like a time capsule into antiquity. There was a genuine human element to their performance, reinforced by the cordial way in which they interacted with members of the audience. Just minutes after they left the spotlight, members of the band made their way into the crowd, greeting eager fans.

Bluegrass music is of incredible cultural importance to the Blue Ridge, reflecting the distinct Appalachian values of community, pride and self-sufficiency. The music itself is an art form that has lasted the test of time. Where other genres of music have adapted and morphed in the face of technological advancement, bluegrass has preserved its traditional and unique sound.

“It’s kind of like one of the only Native American-born musics that there is,” Moore said after the show. “There’s a lot of us that don’t want that to ever go away. We like to evolve and mess around with the music, you know, at times, for our own enjoyment, but we know what the roots of it are, and the way it should be played. It would be sad if it evolved into something else and lost all that.”

Dave • Jan 19, 2023 at 8:27 pm

What a fantastic article!