Bret Easton Ellis in his novel Less Than Zero characterizes the L.A. sun as a sort of incessant breath, whose orange-white effulgence melts identity. He gives us “Images of teenagers, people my own age, looking up from the asphalt and being blinded by the sun.”

Now, Less Than Zero has nothing to do with tennis (the sport is used only as a point in the characters’ bulletin of wealth), but Easton Ellis’ description of the sun is great because it is Spartan, intensely moment-specific but seeming to permeate time.

Melbourne, Australia, from the 10th of January to the 28th, is a city scrutinized by the summer sun. Its rays focus all attention on Melbourne Park, the consummate host of the year’s first Grand Slam, and eventually the world receives a champion, wrought out of Australia’s crucible of concentrated radiance. Solar spotlights amid a portrait of fire incense players to compete in front of a crowd just as sweaty and ready to burst with heat at their performance.

This year’s Australian Open brought another unique set of challenges, though, with the usual top crop of players sprinkled unusually throughout the draw. Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and the late Sir Andy Murray, who seems to be on indefinite injury leave, were not concentrated in the action. They had early, uneventful departures from competition.

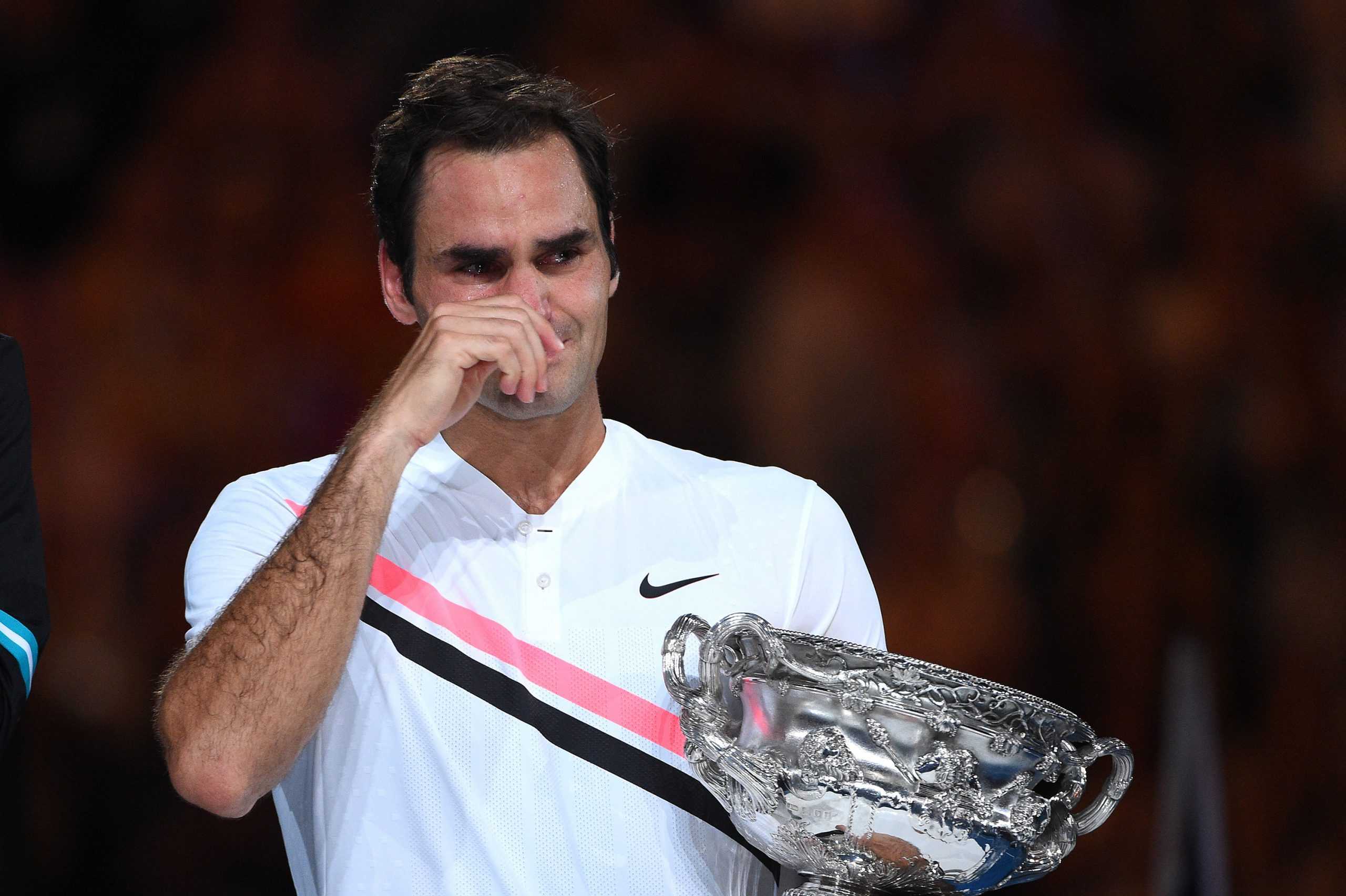

But for Roger Federer, it was a different story. In Melbourne this year, Federer lifted the trophy yet again. He showed the world that the usual age-associated denouement exists as narrative convention, and that Roger Federer is the furthest thing from convention the world of tennis has ever seen.

Ripping through a draw of 128 in straight sets all the way to the final, Federer displayed what we’ve come to love and expect — strokes like liquid mercury, gestures into corners with microscopic precision and a balletic whippishness that has set the precedent for economical sport.

I do not know what animates this man, but whatever it is, it is some protean substance nearing the divine, incessant and doggedly triumphant.

Marin Cilic was Federer’s opponent in the final, and the match went to five sets, with final score of 6-2, 6-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-1 in favor of Federer. When Federer spoke after, his speech rolled through its acts, on a more than emotional vector, voicing thanks to venue and family, sport and sponsor. But it was when Federer was congratulating Marin Cilic on his efforts, when he told his competitor he had “another great tournament” that there seemed to be a slight reveal. Federer went on: “Congratulations on world number three … Keep doing what you’re doing, and you can achieve more.”

The words themselves are banal, but there was a certain emotional inflection Federer turned on, when he said “keep doing what you’re doing.”

A sort of subtle vocal tremble, like the shudder of a maple seed, during his live speech, seemed to me a profound moment.

“Keep doing what you’re doing,” dripped with the schmaltzy tears of disbelief, as if Federer could barely believe what he was still doing, as if he thinks it will have to, must, come to an end soon, as if the (not much) younger Cilic (or any player) is someone Federer envies because no matter how much he himself defies time, its proximity now haunts him.

Federer has nearly nothing left to “achieve,” but his spirit is one that craves achievement. That spirit itself, no matter the physical deterioration, is evergreen. The basic duality of this Federer will have to deal with for the rest of his life, and he knows it. It is as if, when speaking to Cilic, Federer envies the ability to “achieve more,” to have “world number three” be only a stepping stone to an unknown future of greatness. Federer is already inhabiting that future, and everything from here on is brutal and sad. Time is not of the essence, it is Federer’s essence, and he is beginning to now consciously revolt against it, even if only in subtle ways. Nietzsche defined resentment as “the will’s revulsion against time and its ‘it was.’”

Federer is beginning to see the horizon of resentment and he is beginning to see everything won now as pitted against the memory of youthful triumphs. We can try to sympathize with this great man, but like many great men any attempt at empathy is as good as a fist clenched with air.