Film has been weaved into the fabric of my intellectual life.

I see film not just as entertainment, but as an art object, grounded in a specific historical context, failing or succeeding at expressing meaning or aesthetics by virtue of its constituent parts — score, camera work, color scheme, casting, etc.

This intellectualization of film, for me, stems from a high school seminar I took entitled Film and Lit, which was not so much “film” and “literature,” disparate or even conjoined, but more so a class that taught one to become film literate, and to approach movies as one would approach literature, or any other high art. We watched films like The Graduate, Harold and Maude, The Usual Suspects and Run Lola Run, analyzing each and writing reviews and research essays.

Before this experience, I went to the movies and watched passively. I knew what was and was not “good,” in the broadest possible sense, but didn’t know how to articulate what I felt with the proper lexicon, or even look at film with an eye keener than that which distinguishes Megan Fox from Rosie Huntington-Whitely. After Film and Lit, that malnourished, abortive viewer erected himself into a more confident, agile one.

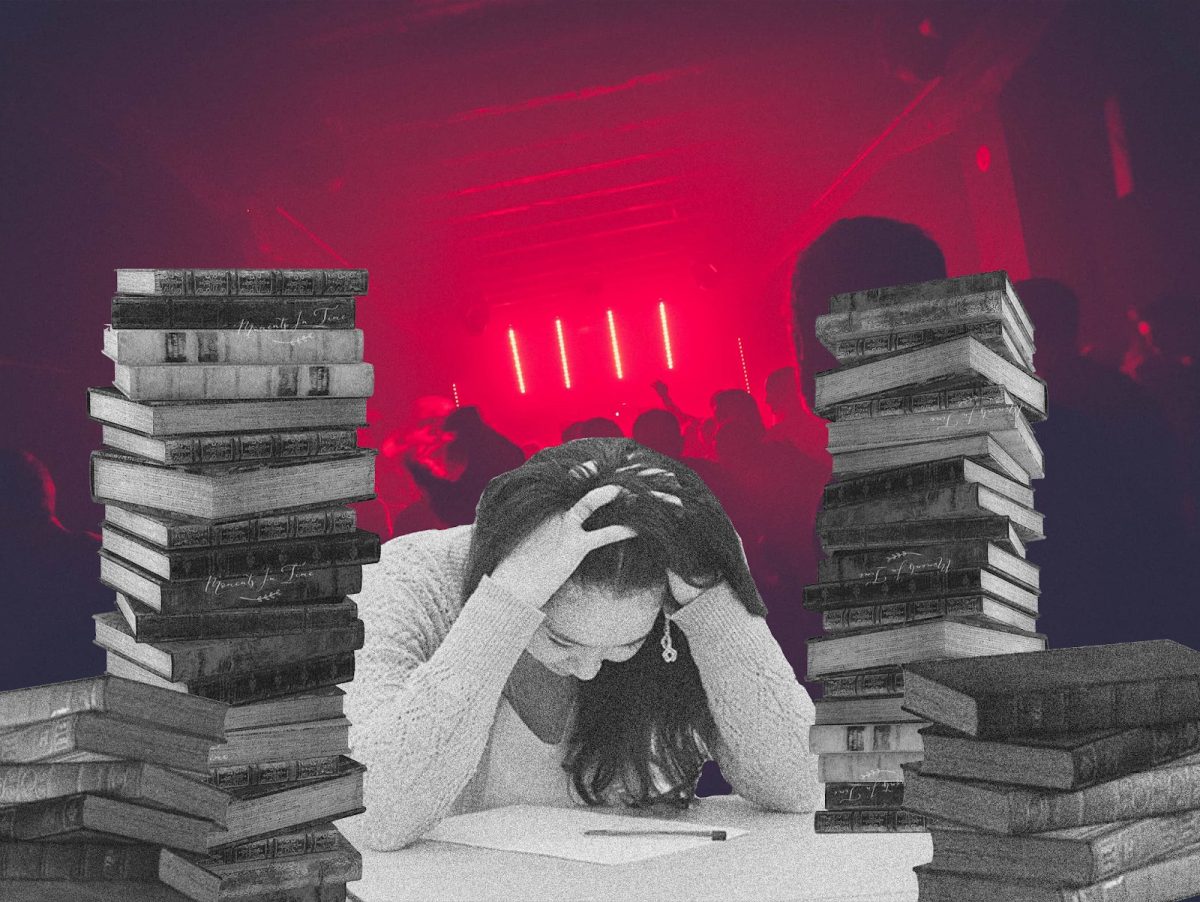

Soon, my liking of film became a cinephilic disease — missing social events and postponing meals became standard. I was overwhelmed by the artistry of movies, just as I was by books earlier in my life.

I say all this because the discerning eye can tell that there is something amiss in American movies. Reducing cities to rubble, while erumpent heroes whizz through the streets, killing off the last of their indefatigable enemies, has become the trite state of the American blockbuster. Sure that stuff can be fun, but moreover that stuff makes money. And there is indeed an entire history behind how the movie industry came to be less auteur-ish, dating back to the 1970s and the New Hollywood.

But this isn’t a history lesson — although one could argue how else can one interpret the present if not through some sort of historical consciousness? It is a short dive into contemporary movies as cultural markers.

The director Paul Schrader said, during an interview with Bret Easton Ellis, that during the New Hollywood of the 1970s “movies were at the center of the social discussion. People turned to movies because they had questions … about civil rights, black power, women’s rights, gay rights, militarism, conformity, drug use,and they wanted the movies to say … here are films that address these anxieties we’re all sharing. And the moment a society turns to artists for answers, great art will emerge.” That last sentence is the thrust of Schrader’s entire argument. Movies are no longer the centerpiece of social discourse; instead, they are mostly offhand entertainment, a thing that allows you to take your mind off of the important things.

There is of course value in distraction, in pure, unadulterated entertainment, and I realize that viewing film as pure entertainment is also part of it, that brow-beating it with analysis sometimes takes away from its purity as a medium, sort of like deep analysis of Wilde or Beckett can eventually detract from their whole “point.” But one cannot lament about the movie industries trite releases and also refuse to accept why is it so. It makes sense that as the liberal arts depreciate in our collective consciousness, art will continue its sharp decline.

But in an era of instant gratification, with likes and texts and emails constantly charging our egos, it is hard for a nuanced film to gain any traction (i.e. generate revenue), because essentially the new Transformers movie is, in its perpetual explosions and endless climaxes, an iteration of the tech world we inhabit, of the quasi-, five-second-fulfillment that paradoxically takes the very thing it seems to give —happiness.

It is through the lens of our own technological attention spans that we can understand the current state of art. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be remedied. There are still great artists creating great films — Noah Baumbach, Paul Thomas Anderson, the Coens — but there are increasingly more difficult barriers to entry. The onus is on the viewer to search for and be desirous of thinking man’s movies.

So read a book, watch a movie, stare at a painting and think about it. Maybe the endorphins will begin to flow freely, not melt like snowflakes.