Reflecting the times

Every three years, students travel to New York to buy contemporary art. But what happens to it when it gets here?

April 12, 2023

As soon as I entered J.D. Wilson’s home, I could tell he is a man who loves art. Small sculptures sat on shelves, and large paintings hung on the walls. He proudly displays his grandchildren’s crafts around the dining room. A cardboard cutout of a woman sat on one of the chairs at the table. Yes, a cardboard woman.

I found it odd when I first entered the dining room, then I learned the story. It was a cutout of his wife’s best friend, Frances. Wilson gave it to his wife as a gift before her college reunion so that Frances, who couldn’t travel to the reunion, could be in the photographs. I didn’t know you could show love through a cardboard cutout, but now I do.

I spoke with Wilson over lunch in his Winston-Salem home a couple of months ago. When I told people I was working on a story about Wake Forest art, they said, “talk to J.D. Wilson.” A 1969 graduate of Wake Forest, he is a stalwart supporter of the Wake Forest art collection and a big name in the Winston-Salem creative economy, serving on the Board of Trustees for the Creative Center of North Carolina.

For Wilson, art can be beauty, gift, keepsake and utility. Even the plates for our lunch were painted in bright primary colors.

In the middle of our meal, Wilson sprang up from his seat to retrieve something. I waited for him, staring at the art around his home and making awkward eye contact with cardboard Frances.

When he returned, he placed an event program on the table.

“I found this while going through some stuff we had at storage,” he said. “This is the program, the physical program, from that collection that I saw that first opened my eyes to the world of art and the importance of art.”

Wilson was referring to an exhibit of the art bought on the first Wake Forest University student art buying trip in 1963. Four years later, Wilson went on a buying trip himself.

“My father taught me that, anything that’s important, write the date on it,” Wilson told me.

Sure enough, he flipped to the back of the program where “September 15, 1964,” was written in pencil. It was a day Wilson will never forget — one that turned him into a lifelong lover and supporter of the arts.

For Features, Christa Dutton investigated the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art.

Art among us

The student art-buying trip is one of the most unique experiences Wake Forest has to offer. It all started in 1963 when Wake Forest’s Dean of Men and College Union Adviser Mark Reece and faculty members Ed Wilson and Allen Easley drove to New York with two students who they tasked with purchasing pieces of contemporary art. Wake Forest did not even have an art department at that time.

Since then, a small group of students has continued the tradition and traveled to New York City every three years during spring break to purchase contemporary art for the university’s collection with university funds. There is no other program like this at a university in the country, according to University Art Collections.

Wake Forest gives the students $100,000 with only one instruction: buy art that “reflects the times.” Students spend their days in the city visiting galleries and spend their nights deliberating their findings. They debate which works to buy, evaluating their artistic value as well as how the work will fit into the collection. They consider factors like which artists they want to be featured. The last buying trip cohort only purchased work from female artists or artists of color to add more diversity to the collection. Before that trip, less than five percent of the collection was from artists of color.

Students also have to talk money. If they buy one piece, that may mean they have to cut another to stay within their budget. They also have to consider shipping costs; it’s easier to ship a painting than it is a sculpture.

Formerly known as the Student Union Collection of Contemporary Art, the works purchased on the buying trip are now in a collection called the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art. It is Wake Forest’s premier art collection and will celebrate its 60th year in 2023. The collection now has more than 200 pieces by more than 100 artists, ranging in media from paintings to print to photography to sculptures. The collection is a time capsule — documenting the art that Wake Forest students thought reflected their time.

Most of the collection is now displayed in either Reynolda Hall or Benson University Center. These pieces are fine art and would typically live in a gallery or museum, but at Wake Forest, the art lives among the students.

The art’s location poses an interesting question. What is a piece of art’s relationship to the space it occupies? How do you balance the accessibility of art with the preservation and sacredness of art?

Wake Forest also asked those questions and sought answers. In 2016, former Vice Provost Lynn Sutton initiated a report of the Hanes Gallery, stArt Gallery and the University Art Collections. Dan Mills, an art museum director at Bates College, visited Wake Forest to conduct the review, and he discovered that one of the biggest challenges for Wake Forest would be the care of the Reece Collection (then called the Student Union Collection). His report said the works were of “high scholarly, aesthetic, historic and monetary value,” being worth well over $4 million but were displayed in “insecure, unstaffed and high light level spaces.”

He noted that the university would have to grapple with the school’s long tradition of public art with the need to provide proper stewardship. Resolving this tension doesn’t come without its challenges — challenges that are both practical and philosophical.

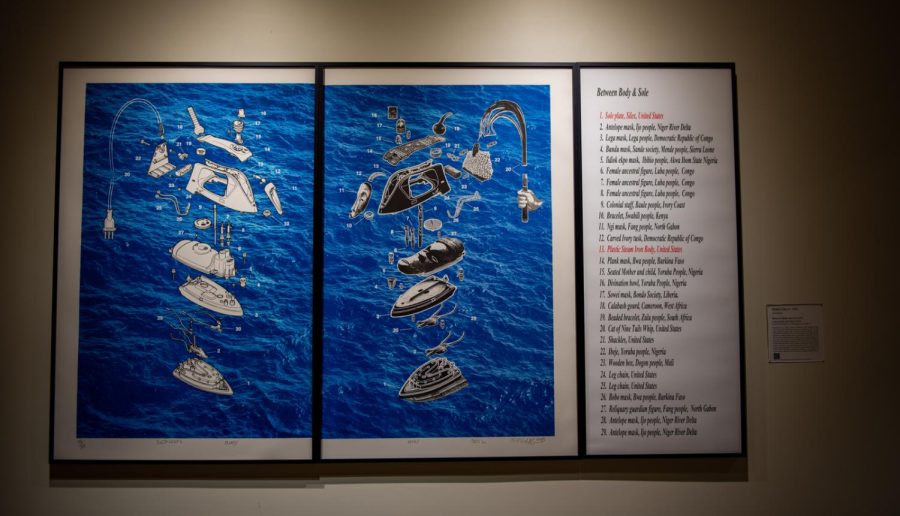

Willie Cole’s “Between Body and Soul” was purchased on the 2021 buying trip.

A daily intervention

Kayla Amador (‘19) was one of those kids who scribbled on the walls. She remembers that, instead of yelling at her, her mother would say “We should take her to art school!”

So when Amador arrived at Wake Forest, she immersed herself in the arts, taking as many courses as she could and working at the Hanes Gallery in Scales Fine Art Center. Amador went on a buying trip in 2017 as a sophomore, and she continues to work in the arts today as a freelance designer and visual artist. Having been one of the students who purchased art that went to live in buildings like Reynolda and Benson, Amador has thought deeply about the virtue of a work’s home.

The accessibility of Wake Forest’s art collection certainly has its benefits. It’s like living in a gallery. Students don’t have to drive off campus to experience incredible art. They don’t even have to enter a museum, a space that can be off-putting to those who wouldn’t call themselves art lovers. The art is where students study, work, eat and hang out. As Amador puts it, “It becomes part of your space, part of your home.”

Dr. Jennifer Finkel, the university’s art curator, believes that art can be a “daily intervention in your life.”

“Whether we’re going to Benson to study or pick up our mail, or to the copy center, or to get food, or [to] the Women’s Center or the Intercultural Center — there could be this moment where you don’t have to walk into a museum or a gallery to have an art experience.”

As curator, one aspect of Finkel’s job is to decide where the art goes. She gives this great thought, considering who visits spaces the most and thinking about what art they want to see.

“I think about who’s in those spaces,” Finkel said. “Who’s going to the Intercultural Center? I wanted that to be more like a global representation of international artists, versus the Women’s Center or the LGBTQ+ Center focusing on female-identifying artists and other artists. I really tried to think about who’s in different spaces and how the art can have an impact.”

According to University Art Curator Dr. Jennifer Finkel, it is difficult to teach from artwork in the Reece Collection because it is hung in often-busy hallways.

Everywhere and nowhere

With public art, one of the first challenges to think about is contextualization. In a museum, works can tell a story, but in hallways, Finkel says there’s no way for the works to be in dialogue with one another. That’s not without trying, though. Reece Collection works have labels next to them, and some even have QR codes that can take viewers to more information. That is, of course, if viewers take the time to read them.

Another challenge with hanging the works in Benson or Reynolda is that it is difficult to teach there. Finkel says that the Reece Collection is academic and should serve as a resource, but those buildings don’t work as teaching spaces.

“It is near impossible to really teach from the art,” she said.

While the collection is certainly accessible to students, few know about it. Or if they do, they don’t know that it is fine art. Finkel often leads tours of the collection for students, and usually, only half the group knows that Wake Forest has an extensive art collection.

“There are students who will actually go to Benson to have an art experience,” Finkel told me. “Then there are a lot of students who are studying in Benson who probably don’t even notice it. I mean, it could be poster art. Yeah, it could be posters. It’s everywhere and nowhere.”

In 2017, Dr. Kevin Murphy from Williams College conducted a review of Wake Forest’s art collection, much like Mills. In his report, he wrote: “…works in Benson are so visible as to have become invisible.” Everywhere, and nowhere.

Murphy’s report also raised alarm about damage to the art. He wrote: “WFU has a choice — it can continue to let its collection deteriorate or not. The display conditions I witnessed are, frankly, appalling.”

Murphy only confirmed what art faculty like Finkel have known for years — that the collection is in danger.

“As soon as you have artwork in any public space, it’s subject to any kind of UV light, natural light. The degradation starts almost immediately,” Finkel said. “Artworks are getting damaged by light. Artwork is getting damaged from accidental impacts. Artwork is getting damaged from vandalism.”

Alex Katz’s “Vincent with Open Mouth” has been in storage for 10-12 years, according to Finkel. The piece was deemed too valuable to display in public.

Treasures stored away

Just under three miles away from campus, pieces from some of the university’s nine art collections sit in storage. Some are there to rest in a climate-controlled space and take a break from light exposure and other harms presented by the outside world. Others are there because they are too valuable to be in public.

One such piece is Alex Katz’s “Vincent with Open Mouth” — an eight-foot-tall oil painting on canvas purchased on the 1973 buying trip. Finkel said it has been in storage for 10 or 12 years.

While it was displayed on campus, it received dents from chairs bumping into it, and then in the ’80s, someone drew a penis on the canvas. It was restored, and it eventually became too valuable to be vulnerable to either accidental or intentional damage.

Another piece that was vandalized was Robert Colescott’s “Famous Last Words: The Death of a Poet” — one of the Reece Collection’s most valuable works, bought on the 1989 buying trip. The painting was vandalized in April 1992 when it hung in Benson. The painting is a montage of a poet’s life, depicting his vices like gambling and alcoholism but also his romances: the Black poet is shown in bed with a white woman. Someone took a black marker to the woman’s body, making her skin darker to match the poet’s. Fortunately, the painting was restored and hung back up, this time in Reynolda.

Then, in the spring of 2020, another one of Colescott’s paintings sold at Sotheby’s for $15 million. The very next day, Wake Forest’s Colescott was taken down.

“One of the most important contemporary artist’s works is in storage,” Finkel said. No art museums in North Carolina have a Colescott painting.

Both the Katz and the Colescott have an insurance value of $1 million. If it was safe, Finkel says the two paintings would “1000%” be on display.

As curator, Dr. Jennifer Finkel decides which pieces go on display and which are stored in racks.

Cūrātor

In Latin, the word “curator” means “one who has care of a thing.” A manager. A guardian. A trustee. Finkel sees herself as all of these things — a steward of objects. So it’s a challenge to her that she can’t hang two of the collection’s most impressive pieces — pieces that students acquired — because she doesn’t have the proper space to care for them.

“Philosophically, I feel like we, as an institution, are not valuing this collection,” Finkel said. “We value the buying trip. We value the $100,000 that we give to students every four years, now every three years. We are not valuing the art when it comes here. Hence, we are not valuing the artists.”

When I asked Finkel what the solution would be, I could tell she’d dreamed of it before. She imagines a safe, dedicated, temperature-controlled, humidity-controlled environment. Where there is open storage, so the Colescott and Katz are safe and able to be viewed. Open racks. Flat files. A huge conference table where students can view art and discuss it. Students could curate shows. There could be performances. Other disciplines could share the space, as well. Chemistry students could learn the science of conservation.

Finkel’s dream space doesn’t mean that the art in Reynolda or Benson would have to go away. Some of the Reece Collection and other student art could still be there.

“It has been historically in Wake Forest DNA, in our fabric, to have art in the public,” Finkel said. “And that’s wonderful. There can still be. It’s not an either or, it’s a both and.”

Mills suggested a vision similar to Finkel’s. He proposed that the university divide its collections into two categories: a museum collection for works that support the university’s academic mission and a campus collection for works that would enhance campus but do not meet museum quality.

Since Murphy’s and Mill’s report, the university has not announced any plans for a dedicated space for the Reece Collection, although Wake Forest has certainly been thinking about its academic space needs. As a part of the strategic framework, Wake Forest President Susan Wente created a University Space Planning Group to ensure the management of the university’s physical assets. In her February 2023 blog post, Wente said that academic space renewal was one of her “highest priorities as President.”

Wake Forest has long valued art of all kinds, but it must balance its desire to make art accessible and its obligation to preserve the artwork itself.

In our DNA

The American actress Stella Adler once said: “Life beats down and crushes the soul, and art reminds you that you have one.”

As a university in the city with the country’s oldest arts council, art is in the DNA of Wake Forest. It’s long been a value of our leaders and students, as shown through Reece’s revolutionary idea to let students purchase art for the school.

Every few years, students will keep traveling to New York to purchase incredible pieces of contemporary art. They’ll be shipped back to campus for all to see. No matter where that is in the future — Reynolda, Benson or an exhibition space — art will fill our Wake Forest home, just like it fills Wilson’s. The Reece Collection will continue to be many things to us — a teaching tool, beauty to our spaces, a time capsule of history. People like Wilson, Amador, Finkel and other faculty in the Department of Art will keep stewarding it and showing it off. The Reece Collection will reflect our times, reminding us of the life we’ve lived and that, through it all, we still have one.

J D Wilson • Apr 16, 2023 at 2:30 am

Tonight, at a donor event at Reynolda House, a leading arts professional told me this is the best article he has ever read! Congratulations Christa!

Laura Mullen • Apr 13, 2023 at 12:59 pm

A well-researched, beautifully written, and exciting article which offers both an account of the collection’s past, and (potentially) a map for its future. So grateful for the recognition of the current difficulties teaching from the collection (displayed in hallways and offices and lounge areas) and the real danger to the art. I echo the plea for a space for the art: it should ideally be a space (open to the public) which will allow this extraordinary treasure to educate, delight, and inspire the WinstonSalem community, the North Carolina audience–and art lovers across America and the world.

J. D. Wilson • Apr 13, 2023 at 10:26 am

Wow. Takes my breath away. Opportunity (and Threat) so well stated. What excellent journalistic curiosity that’s woven into a thought-provoking narrative. Thanks for presenting a broad perspective as we consider the motto that guides us, pro humanitate. Thanks to you and OG&B.

Emily Clark • Apr 13, 2023 at 9:39 am

An important article that highlights the beauty around us everyday, and the value our University places on our having that experience. Christa’s article is especially helpful in gaining an understanding of the Reece Collection, its origin, and where it stands now. A must read!