Core curriculum change stalls

The university is planning new course requirements that focus on diversity and inclusion efforts

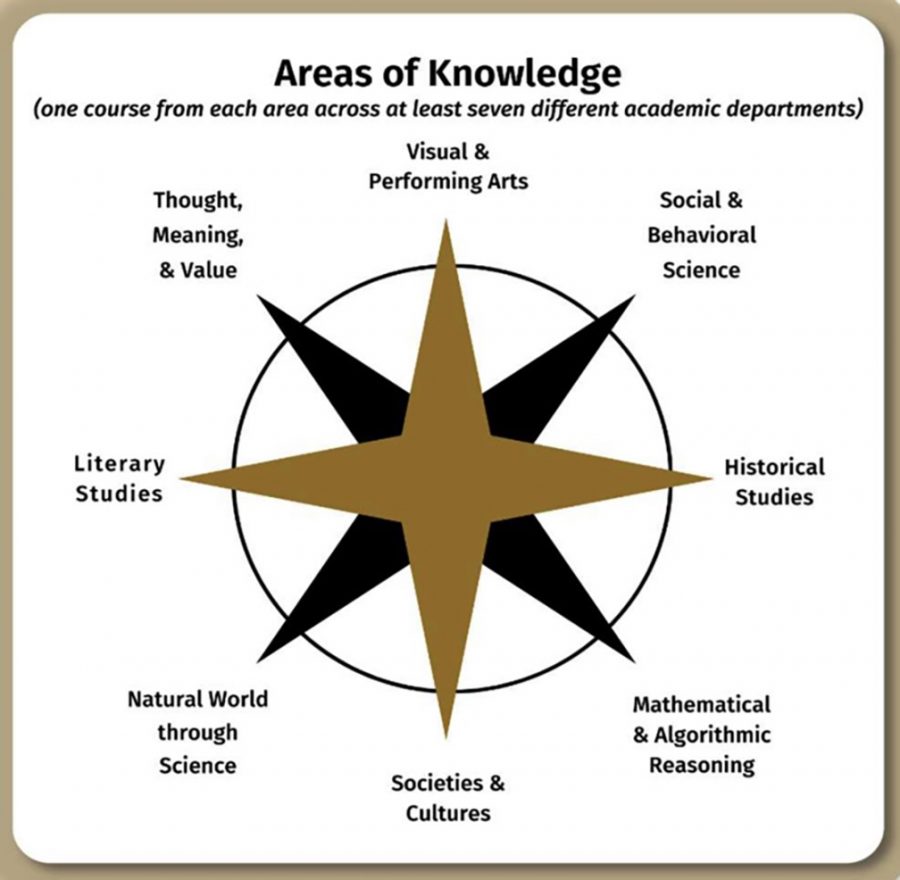

The university plans to implement seven new areas of knowledge (Photo courtesy of the Committee on Academic Planning)

November 12, 2020

In the wake of Black Lives Matter protests this summer, the university’s academic curriculum was primed for an overhaul reflecting the need for greater awareness of social injustices and systemic racism.

However, as the proposal stalls in committee procedures, some faculty worry the university is rushing on a new curriculum that lacks the ability to properly address social and political inequities.

The proposal, called the 21st Century Citizenship Requirements is slated to replace the existing cultural diversity and quantitative reasoning requirements.

The new requirement is part of a university-wide push to include more diversity and inclusion training for students and faculty.

The curriculum change, which has been ongoing for years, is intended to expose students to problems of systemic inequities on a national level, while providing a greater understanding of other peoples and cultures. It provides for four required courses: Cross-Cultural Analysis, Community in the U.S., Ethical Inquiry and Quantitative Data Analysis.

However, many faculty members say that the new proposal doesn’t go far enough — and that it might be problematic. In particular, faculty have targeted the College Curriculum Review Committee (CCRC), which wrote the proposal, as lacking expertise in the necessary areas.

“Part of our critique of the 21st Century Citizenship proposal is that the committee that developed it was well-meaning, but they didn’t include folks with expertise on the issues,” said Professor Kristina Gupta, a member of faculty group Wake Forward. “We think the 21st Century Citizenship proposal reflects that. It reflects that it wasn’t based on sufficient expertise.”

Likewise, some professors worry that the concept of “non-Western” civilizations described in the Cross-Cultural Analysis requirement might mislead students.

“I feel concerned that the definition of a category as being basically the non-Western world can really underscore for students the idea that there’s kind of a white world, which is the U.S. and Europe and that there’s the whole rest of the world, and that the rest of the world is somehow the same, is somehow other,” said Mir Yarfitz, a professor of history.

The committee that wrote the report, the CCRC, dissolved after sending it to the Committee on Academic Planning (CAP), a permanent committee which deals with curriculum and other academic issues. CAP has been standing by 21st Century Citizenship Requirements despite the concerns, though the committee’s chair, Miriam Ashley-Ross, said it is open to amendments or revisions.

“This proposal was the result of two years of work by the CCRC, and what they came up with really reflected curricular priorities that the faculty identified,” Ashley-Ross said. “These were all very thoughtful proposals. Not to say that they’re perfect — they can certainly be tweaked — but they were not just grabbed out of thin air.”

Faculty and members of CAP emphasized that faculty members have a wide range of opinions on the issue. However, many opposed to the proposal would like to see a new committee created to rework the requirements.

“We’d like to see potentially a new committee formed where the members have academic expertise in issues of social and political equality, white supremacy, systemic racism and for that committee to come up with a new proposal for replacing the [cultural diversity requirement] that would give our students better tools for understanding systemic inequality,” Gupta said.

Though CAP is oriented towards revisions of the current guidelines, some faculty members take issue even with the name “21st Century Citizenship Requirements.”

“The concept of citizenship is a problematic one,” said Yarfitz. “We felt that it would just flag any students, faculty or staff who might be undocumented, who might be immigrants. It’s a very poorly chosen term that should not be used as a metaphor. It excludes certain groups of people.”

As disagreements persist, the proposal itself is stuck in a logistical nightmare. COVID-19 has upset basic actions, like the ability of CAP to vote on proposals. The group, which can only meet online, can only vote in-person — and to change that bylaw, they would need to vote in-person to do so. That, combined with the committee’s inability to edit proposals and a lack of a committee to do so, means that the proposal is in limbo for now.

“The truth of the matter is that all of these processes, they take a long time because we want to get it right,” Ashley-Ross said. “We want to make sure everyone’s voice is heard. We don’t want to cut off discussion too early to meet an artificial deadline. But we’re working on it.”

Pilar Agudelo, the chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee in Student Government, took a different point of view. She said that her committee has been trying unsuccessfully to get involved with the curriculum overhaul for months.

“It’s been kind of like a whirlwind mess. We’re kind of in the dark,” Agudelo said. “The one thing that I think is going wrong is that there’s no definitive process.”

Though change is slow, faculty and students expressed the desire to move forward. Senior Emily Claire Kibbe, the student voting member of CAP, said that the Black Lives Matter protests over the summer are a major driving factor in getting the proposal, in some form, off the ground.

“I think that any curriculum change is going to be a major change in the university, and the university is such a large organization that it’s going to be a slow change,” Kibbe said. “However, I think given everything that happened in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death and so many things that have happened since, there is a greater push among faculty and students to make this change.”