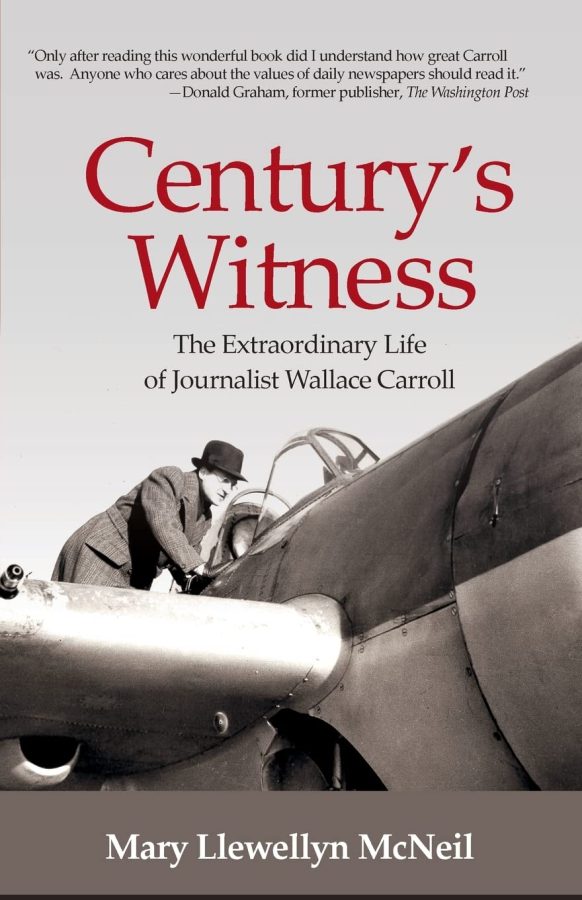

Mary McNeil recounts history on the run

The former OGB editor wrote a biography of famous journalist and Wake Forest professor Wallace Carroll

McNeil’s book covers the life of journalist Wallace Caroll.

September 28, 2022

“Century’s Witness” is Mary McNeil’s first full-length biography, which details the life of Wallace Carroll, one of the greatest journalists of the 20th century. Carroll was a diplomatic reporter in the lead-up to World War II and also played a vital role in the spread of information for the Allies. After the war, Carroll worked for the Winston-Salem Journal as the paper’s publisher and editor, leading the Journal to a Pulitzer Prize. Carroll also taught constitutional law at Wake Forest University for the remainder of his career, where he would meet McNeil, one of his students.

McNeil is a former editor and writer for the Congressional Quarterly. McNeil also worked as an editor at the Smithsonian Institution and the Academy of Sciences, and as a journalist at the Winston-Salem Journal. During her 28-year career at the World Bank she launched two global publications, “The Urban Age” and “Development Outreach”, and wrote the book “Demanding Good Governance, Lessons from Social Accountability Initiatives in Africa”.

Tell me a little bit about your time at Wake Forest and how you came to write this book.

I graduated from Wake Forest in 1978, and for three years I wrote for the Old Gold & Black and was Associate Editor my junior and senior years. And at the time, I worked for the Winston-Salem Journal as a sportswriter and did an internship there as a news reporter. You couldn’t major in journalism back then, but I did have a professor named Wallace Carroll who gave a class on the First Amendment. There was something about him, that even though he never talked about what he had done, or how accomplished he was, you always wanted to do well for him. You knew there was something really special there. After I left school, I was doing different things, working at the World Bank, and I just kept thinking to myself, “Boy, I hope Mr. Carroll would be pleased with what I’m doing.”

Eventually, I was in London, and I came across a book about three Americans that had helped bring us into World War II. Mr. Carroll’s name kept popping up throughout the book. And I had no idea, and wondered, “Is this really my professor?”, and it was because he was the head of the United Press in London at the time, and that sort of piqued my interest. I just started googling him, and it was unbelievable. It was a bit like peeling an onion, in a way, because the more I found out about him the more interesting he became.

In your article in Wake Forest Magazine, you describe Carroll as a “mysterious teacher”. Is that a part of his modesty as an individual, as a journalist?

I think that was part of his personality, which is an interesting contradiction because especially nowadays, the personalities that go into journalism, particularly TV or any kind of media journalism, have pretty big egos. I think that was why he was so well-liked because he had a modest demeanor and wasn’t out there making it about himself, but was making it about the story.

That extended to a lot of his work in journalism. When he was an editor at the New York Times, they hated hyperboles, like “Christ, how the wind blew” stories that were not very earth-shattering or unprecedented. And so that has changed a lot, but maybe the pendulum will swing back. I think Carroll introduced the opposite of that style; a kind of analytical style of reporting, getting behind the facts and getting deep into a story.

Wallace Carroll was a firm believer in the written word, even when radio broadcasting and other forms of journalism were developing at the time. Why did he stick to print journalism?

In my mind, there are a bunch of newspapers like the Washington Post, the New York Times, or the LA Times that are still doing that kind of written reporting, which is really good. They’re the ones that do the investigative work, which is hard work. If you look at the cable news media, they’re not really doing the hard work, they’re just sort of regurgitating the investigative work from the written media. So I still think that print journalism is really crucial.

But nowadays, what’s different from Carroll’s era is that we no longer have that quality of reporting at the local and regional levels. In the book, I mention a columnist for the Washington Post named Margaret Sullivan who writes about the death of local journalism. I think local journalism exists, but it’s not as prevalent.

What do you think his views would have been on the state of journalism today?

I think he would be pretty appalled at the amount of coverage that people get for telling lies. There’s no obligation to report on or give a lot of publicity to lies that people are telling. So I think we’ve gone the wrong direction on that one and I liked [Carroll’s] theory on objectivity in journalism and how he related it to the McCarthy period in the 1950s.

There’s an interesting quote in the book that says: “Journalism is history on the run”. Could you explain to me the significance of this quote?

When I was working as a journalist, it was a lot of capturing history, but you’re under a daily deadline. You have to produce stories quickly and beat out the competition, which is hard, and so it’s kind of a fast take on what’s going on in the world. Now there are so many sources of information that you can take a little bit more time to write a story, but back then, when you were working for the United Press, your main goal was to beat the Associated Press. In the book, there’s a scene in which Carroll is at a riot in Paris, and there was a man who was shot right next to him, who’s dying. And the first thing Carroll thinks after the guy has died and he has done all he can for him is that he has to run to the phone to call in his story.

What do you think young journalists can learn from Carroll and how he pursued journalism in his life?

I love the quote at the beginning of the book: “I became a journalist to become as close as possible to the heart of the world.” I think that there is no more interesting profession than journalism. There are drawbacks of course, but if you want to have an interesting life, meet interesting people, and be a part of history – I don’t think there’s a better profession. This is an optimistic book for young journalists because they can look back and remark on the difference [Carroll] was able to make, his integrity, and the interesting life that he led.