Wake Forest community divided on ChatGPT’s role in academic writing

Students and professors at Wake Forest share their opinions on ChatGPT’s influence on academic writing

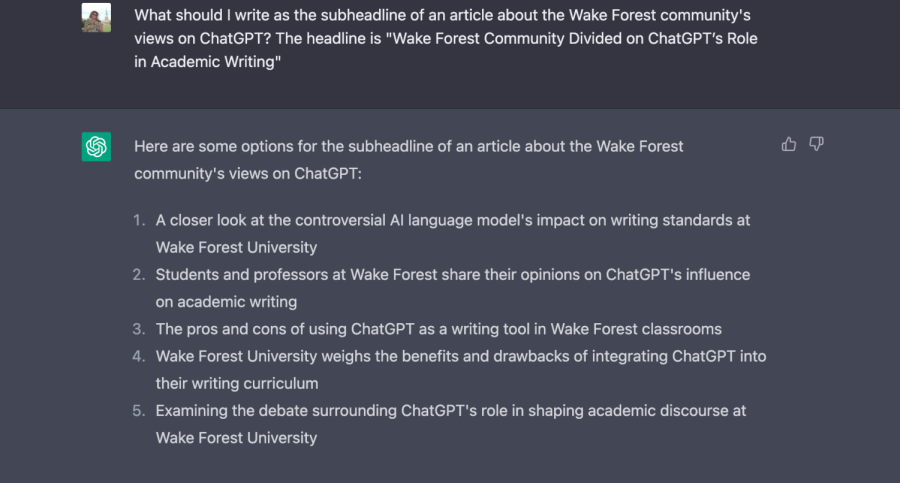

Online Managing Editor Aine Pierre, who was stumped while writing a sub-headline for this piece, consults ChatGPT for answers.

March 2, 2023

When OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November, it began a conversation about the ethical use of artificial intelligence at Wake Forest.

From computer science classrooms to the Writing Center, students and professors are talking about how artificial intelligence impacts learning at Wake Forest. Some STEM students praise the bot as a study tool. However, others who study humanities debate whether ChatGPT will have consequences for academic writing.

AJ Aizpurua, Wake Forest senior and president of the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) Student Chapter, believes ChatGPT is useful for science and math students.

He recommends students use ChatGPT as “extended office hours” to ask the bot questions normally reserved for a professor or teaching assistant.

“I use it mainly to learn more about programming languages that I am unfamiliar with,” Aizpurua said. “The AI will give me a lot of information, but it is much more readable than some of the older documentation that’s on the web that can be very non-intuitive for a student who is trying to learn it for the first time.”

ChatGPT uses previously entered responses and existing web data to generate human-like feedback — helping users plan a Caribbean vacation, develop business ideas or write academic papers. ChatGPT crossed a record-breaking 1 million users within a week of its launch, and an Intelligent survey of 1,000 college students reported nearly one in three college students have used the bot on written assignments.

In fact, this article’s title was generated by ChatGPT. (Managing Editor’s Note: In the online addition, so was its subhead, see the featured image).

As the first line of defense against AI-generated academic papers, Wake Forest’s Writing Center had to react quickly to the rise of ChatGPT.

“By spring break, we do want to have a public-facing policy [for the Writing Center],” Writing Center Director Ryan Shirey said. “This is a place where people come for help with writing in all different kinds of ways, and if ChatGPT or some other AI tool has become part of their writing process, we want to have a way of speaking to those writers.”

As of publication, no such policy has been released.

Shirey is part of an unofficial group of professors on campus who have a Listserv to discuss AI-related issues on campus. While ChatGPT can be a useful brainstorming tool, Shirey worries it may reduce writing to the production of text. He believes that writing allows students to process knowledge from class, which is not something an AI can do.

“I do hold out hope [that] there’s a way of thinking about this technology that neither vilifies it nor sees it as a meaningful replacement for the human activity of writing,” Shirey said.

Yi Zhu, a senior computer science student and Writing Center tutor, is less concerned about ChatGPT’s capacity to mimic human writing.

“At least for now, AI hasn’t reached the level to fully replace our essay writing in college,” Zhu said.

She cited ChatGPT’s use of key phrases, like “on the other hand,” and its repetition of the same basic essay structure. The process of feeding ideas to the bot can help students refine their thesis, but Zhu explained that if a student doesn’t grasp the basic ideas of an assignment, ChatGPT will not magically write it for you — it can only write as well as the information the user provides.

“Based on the algorithm, I don’t think it can generate any new, creative thoughts,” Zhu said. “At some point, it may reach a level of generating academic essays that are readable and reliable enough, but that is from absorbing the knowledge from essays we already have.”

Despite the uncertainty, the Wake Forest community faces regarding technology, Sarra Alqahtani, a Wake Forest computer science professor and AI researcher, remains optimistic.

“Math doesn’t have feelings,” Alqahtani said.

She also said that AI-operated machines having a conscience is a myth propagated by Hollywood movies. In reality, human engineers train machines using data collected from ordinary people. Alqahtani encourages her research students to use ChatGPT to write formal emails and will even incorporate it into future coding assignments.

“ChatGPT is here to stay, so it is better for us as educators to utilize it instead of fighting it,” she said. “I’m personally concerned about replicating our biases in AI machines or models.”

We still struggle with racism, sexism and other oppressive institutions, she added, and those issues can infiltrate AI machines via human engineers. The complicated math equations used to build these machines often make it difficult to understand why they make certain decisions.

“Explaining AI machines is the first step toward understanding and discovering their biases and unfair components,” Alqahtani said.

As the research community looks forward, she says the ethical issues of AI are at the forefront.

“We have to actively, as humans, attempt to ethically use [artificial intelligence],” said Writing Center academic coordinator Caroline Livesay. “It’s out there, and there’s nothing we can do about it.”