Event series highlights ‘autism and the college experience’

Sessions included workshops, a lecture and a student panel

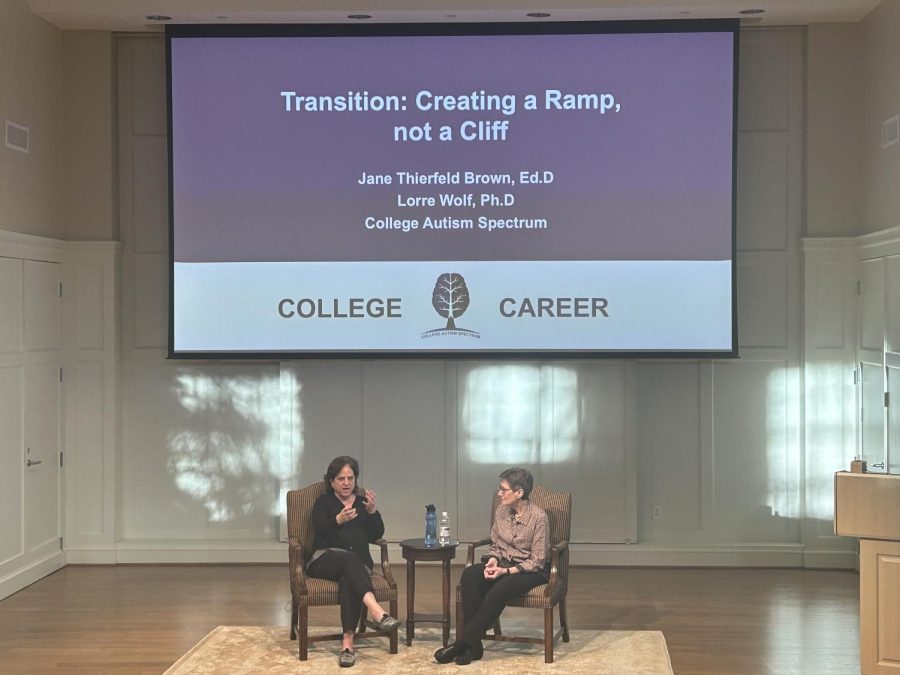

Dr. Lorraine Wolf (left) and Dr. Jane Brown (right) chat before their lecture in Kulynych Auditorium.

March 28, 2023

According to a 2011 study, the most recent one conducted, as many as two percent of college students may meet diagnostic criteria for autism. From March 21-23, a series of events and sessions on Wake Forest’s campus trained students, parents, faculty and staff to support the autistic college students in their homes, friend groups and classrooms.

The program, which was sponsored by Wake Forest’s Center for Learning, Access and Student Success (CLASS), was originally scheduled for late March 2020 before it was canceled. The week’s events included a lecture for parents Tuesday night, workshops for professors and advisers on Wednesday, a student panel (also on Wednesday) and an event at the medical school Thursday morning.

Dr. Jane Brown and Dr. Lorraine Wolf led the programming. Brown is a clinical professor at Yale and director of College Autism Spectrum, and Wolf is director of disability and access services at Boston University.

“I was up in Boston at a training and within 30 minutes, I was convinced that the two people I wanted to bring to Wake Forest were Dr. Jane Brown and Dr. Lorre Wolf,” CLASS office director Michael Shumann said at the Tuesday night event.

At the Tuesday night lecture, Brown and Wolf spoke to an audience of mostly parents about autism and students’ transition to college. The two emphasized the importance of building resilience and strengthening self-advocacy skills.

According to Brown and Wolf, when transitioning to college, some autistic students struggle with self-advocacy because parents and K-12 school staff never gave them the opportunity to learn. Part of this is because of what the two call a “services cliff,” which exists in part because colleges do not have the same legal responsibilities to disabled students as K-12 schools.

“It’s not an equal outcome — we’re not guaranteeing an equal outcome,” Wolf said. The only thing that is guaranteed in college is equal access, which addresses barriers to entry in education (some literal, some metaphorical) and not student success.

At the intersections

Intersectionality in understanding autism was a focal point of Wednesday’s student panel. Panelist Kayla Smith, a third-year at UNC Greensboro, described her experience as a Black, autistic woman.

“Being Black, you have to fight even harder,” Smith said. “You have to be perfect at everything.” Smith also is the creator of #BlackAutisticPride and advocates for intersectionality around issues of race in the neurodivergence movement.

UNCG freshman Isabella Gonzalez also spoke to their experience being both autistic and nonwhite. Gonzalez noted, for example, that their actions were not taken in good faith the way those of their white peers would be.

Additionally, the issue of gender and autism was discussed at both Tuesday’s lecture and Wednesday’s panel. Panelist Holly Thompson, a first-year graduate student at Wake Forest, said she was not diagnosed until her early-20s. Gonzalez, who is non-binary, said they were not diagnosed until after high school, as well, explaining it may have been because they “present as a woman.” This comports with recent research suggesting that women (and those who present as or are perceived as female) are more likely to receive an autism diagnosis later in life.

This is due in part, Brown says, to a phenomenon called masking, where autistic traits are suppressed to conform with societal norms of politeness.

“You have to do things that are, or make it look like you are socially acceptable and accepted in the community,” Brown explained to the audience at the panel. “But often, on the inside, what that does to you is crushing.”

Accommodating autism in the classroom

The core mission of colleges is to educate students and prepare them for careers — as such, the week’s events included trainings for faculty and staff about supporting autistic students.

During the “Teaching Autistic Students” workshop, Brown noted the importance of recognizing differences in behavior between autistic and allistic (non-autistic) students.

“[Autistic] students really want you to get to know them and to tell you how interested they might be in a particular topic,” Brown said, “but eye contact may be an issue…and they may not be able to acknowledge that you’re trying to get to know them.”

Wolf also noted that professors should provide accommodations to ensure equal access to material, but that they should not compromise on their expectations.

“This is a real course at a real university, and the meaning of the degree has to be the same for all students, that’s really what it comes down to” Wolf said. “A watered-down course means a watered-down program means a watered-down degree, and that’s not good for anybody.”

Wolf and Brown mentioned several possible accommodations and options for making courses more accessible to all students, including recording lectures for those with auditory processing issues, allowing sensory objects (such as stim toys) and adding more structure to lessons.

Brown also gave the Old Gold & Black an example of what she believes medical school professors need to be aware of to best accommodate autistic students.

“For people who have sensory sensitivities, a hospital or medical setting would be very disruptive for them, just the smells and the sounds and all the beeping,” Brown said. “So sometimes we have to think beyond the typical academic accommodations and look at how we can meet the access needs of the students so that they can function.”

Autism in college: seeing Wake Forest through the trees

At Wake Forest, the CLASS office’s statistics are well below the two percent figure (which would be 160 students with autism). Schumann, who told the Old Gold & Black by email that 10 or 11 students were registered as autistic with the CLASS office, also said he “wouldn’t be surprised” if many students, faculty or staff were autistic but just had not been diagnosed or were not sharing their diagnosis because it did not impact their academics.

Thompson also suggested in a post-event interview that students may not feel comfortable “coming out” as autistic at Wake Forest due to the school’s “elite” status. Thompson also noted that she knew some autistic Wake Forest students had turned down requests to be on the panel. For purposes of transparency, this reporter was also asked to participate in the panel but declined because she was already slated to cover the event.

“I’m imagining maybe this feels like an elite school, and that people might worry about being judged or being harassed,” Thompson said. “But I took note of [the fact] that students were feeling uncomfortable. And I think that that is something that hopefully can be addressed by the wider community, because it’s not just CLASS’ responsibility, it’s our collective responsibility.”

One student on Wednesday’s panel, UNCG senior Noah Minafo, experienced that kind of judgment and discrimination first hand when he expressed to his friends that he wanted to go to a fraternity party before he graduates college.

“I have four weeks left of school, and every time I try to go to a party, my friends say they don’t think I will be acceptable [to fraternity partygoers],” Minafo said.

Thompson did say, however, that she has found acceptance in her graduate cohort.

“They all know I’m autistic, and they are really, really supportive,” Thompson said. “I love the people in my cohort, and that social environment has been so, so good for me.”

Some Wake Forest students were in attendance at the panel and came away admiring the panelists’ bravery, like senior Maddie Alexanian, who spoke with the Old Gold & Black Wednesday night.

“I think there’s infinite value in listening to people who have stories to share and who have experiences and really haven’t been given the platform to share them,” Alexanian said. “And [the panel] was that platform, and I think that I’m personally really appreciative — it was an opportunity for me to learn a lot.”

Brown shared what she wished students would take away from these events (or just know in general):

“I would really encourage students to be welcoming and to encourage students to not have to feel like they have to fit in, if that’s possible,” Brown said. “We want students to be able to be their true selves on Wake Forest’s campus and not have to try to be someone else or to mask their autism.”

Brown’s comments partially echo Smith’s, who put it this way during Wednesday’s panel:

“I want people to know I’m a human being.”

Correction March 29, 2023: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the age at which Holly Thompson was diagnosed with autism. The story now correctly identifies that she was diagnosed in her early-20s.