On an overcast Saturday last November, bells rang out from the carillon in Wait Chapel at Wake Forest University. Inside, people found old friends, giving them hugs and saying, “It’s been too long.”

Death has a way of reuniting people, bringing together those who have been touched by the deceased for a formal time of remembrance and celebration. Today, no person was being honored. Rather, a church in its last days of existence.

A few months prior, the congregation of Wake Forest Baptist Church voted to disband in November. Members were aging and dwindling in number, in part because of a nationwide rejection of organized religion by young adults who had grown at political odds with the churches of their childhoods. Once the church closed, Wake Forest would not have a Baptist church on campus for the first time in its 189-year history.

The Celebration of Life event was held on Nov. 5 2022, just a couple of weeks before the church would hold its last service. Dozens of people with ties to the church formed throughout the years gathered in Wait Chapel to remember the church’s life.

The chapel is a familiar and beloved place for the congregation of Wake Forest Baptist. Before they moved to a smaller space, the church had always met in Wait — Wake Forest’s defining piece of architecture located at the heart of campus — rent-free. Then, in August 2022, the university announced a new rental policy that would be implemented at the start of the new year. Rayce Lamb, the church’s lead pastor, described this as “the straw that broke the camel’s back” for a lot of their folks. Many congregants already felt like there wasn’t a relationship with the university anymore. This solidified that feeling.

Wake Forest Baptist had always been an outsider of sorts — different from its Southern Baptist peers and the university it called home because of its more liberal views on theology and politics. These differences would go on to create tension between the church and more powerful institutions like the Southern Baptist Convention and the university with which it shared space.

Wake Forest Baptist long held a reputation for being more progressive than its Southern Baptist peers. In the 1960s, the church marched for Civil Rights. In the ‘90s, it provided care for AIDS patients, when many still refused to treat them.Throughout the 2000s, the church fiercely advocated for marriage equality and LGBTQ+ rights. Each week, Lamb began the service with “Welcome to Wake Forest Baptist,” and the congregation responded, “Where all are welcome, no exceptions” — a motto they’ve certainly lived up to. Those gathered at the Nov. 5 service swapped stories about how the church had welcomed them and served as an exemplar of progressive Baptist life.

While branded a “celebration,” the service was still mournful. Like a family at a funeral, church members processed down the chapel’s middle aisle.

There were hymns and prayers and Scripture readings. Lamb gave a homily inspired by a 1958 sermon delivered by a former pastor of the church entitled “The Peril of Neutrality.” In that sermon — delivered more than six decades ago — the preacher urged his church to “boldly pursue justice.” The pastor argued there was no room for neutrality anymore when it came to the injustices of their culture. Lamb recounted ways that the church accomplished that goal as a progressive agent of justice in their city. He then charged his congregation to carry on that legacy and bring God’s justice wherever they go next, making Wake Forest Baptist a circle unbroken.

Toward the end of the service, the audience gave the church a final blessing. They extended their hands toward the communion table in front of the pulpit where photographs of the current congregation were placed. With arms outstretched, a final commendation was given to the congregation to remind them that, because of Jesus’ resurrection, death never has the final word.

Baptist roots

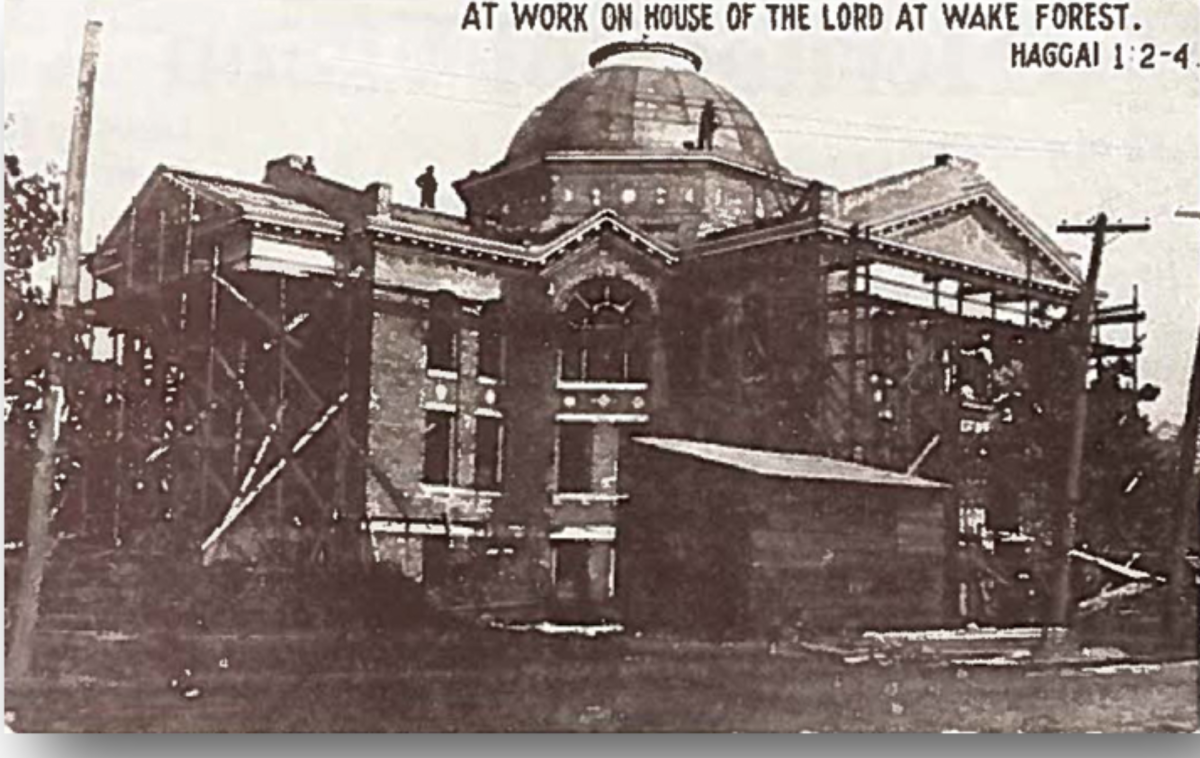

Wake Forest Baptist Church was established on Wake Forest’s original campus in Wake Forest, North Carolina, in 1835, one year after the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina founded the college. That church still exists today under the same name, and the old campus is now home to Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, one of the Southern Baptist Convention’s six theological seminaries.

When Wake Forest College moved to Winston-Salem in 1956, it brought the church with it, keeping the name Wake Forest Baptist and continuing the 125-year-old tradition of having a Baptist church at the center of campus.

As the Baptist State Convention — an association within the Southern Baptist Convention — underwent a conservative resurgence, the university and the convention broke ties in 1986. Wake Forest Baptist would follow suit and leave the Southern Baptist Convention in 2000.

Ditching its Baptist affiliation was a significant shift for the school because of its historical connection to the denomination. As a result, the school’s religious demographics began to shift.

Throughout most of its history, Wake Forest primarily attracted Baptist students. In 1951, 72 percent of the student body was Baptist. By 2005, less than 15 percent were Baptist. In the fall of 2021, the dominant religious affiliation on campus was Catholic.

While Wake Forest became less and less Baptist through the years, it would go on to make a decision demonstrating that it couldn’t shake its Baptist heritage completely — a decision that would put the church at odds with the university.

A union in Wait

In the late ‘90s, two members of Wake Forest Baptist, Susan Parker and Wendy Scott, asked the church if they would perform a union ceremony for them since same-sex marriage was illegal in North Carolina at the time.

The church voted yes, although not without some pushback. While most of the congregation was supportive, some outsiders did not agree with the church’s decision.

One person wrote the church to express concern about the church’s choice, citing verses 18-32 in the first chapter of Romans. In this passage, the apostle Paul writes about how humans have forsaken God, using homosexuality as an example of a sin to which humans had succumbed. The person who sent the letter saw clear Biblical evidence against homosexuality. The congregation, however, interpreted this passage differently and saw no problem allowing the two women to be united.

The church then asked the university’s chaplain at the time, Ed Christman, for permission to conduct the ceremony. Christman asked President Thomas Hearn, and Hearn asked the Board of Trustees. The trustees came back with a no.

A four-person ad hoc committee on the Board of Trustees released a press release on Sept. 8, 1999, that asked the church not to conduct the union. A front-page story printed the next day in the Old Gold & Black reported that the university’s decision was “based largely on historical, rather than contemporary ties to the Baptist church” and that the university wanted to “honor and respect its Baptist heritage.”

Students were outraged. The Student Association for Equality (SAFE) at Wake Forest wrote a petition saying that the trustees violated the university’s non-discrimination statement and urged them to let Wake Forest Baptist perform the union. More than 1,000 students and faculty signed the petition. SAFE also protested by placing flowers on the steps of Wait Chapel and hanging signs on the columns with messages like “Support religious freedom” and “Autonomy.”

At the State of the University address later that month, Hearn told the student body that the trustees’ statement was misunderstood. Nowhere in their statement did the trustees prohibit the church from doing the ceremony, they just asked them not to.

In 2000, Parker and Scott would finally celebrate their union ceremony in Wait Chapel in front of the Wake Forest Baptist congregation. Almost two decades later, the church would make another large step toward the inclusion and affirmation of LGBTQ+ folks.

Making history

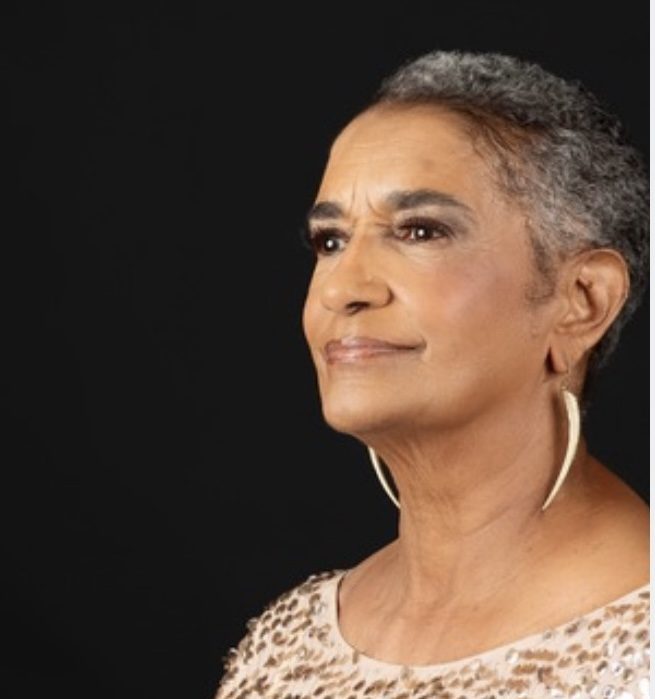

Among clergy members dressed in robes, Erica Saunders walked down the middle aisle of Wait Chapel, knowing that when her ordination ceremony was over, she’d make history.

Those in the processional found their seats as a hymn played. In a few moments, Saunders would be an ordained minister in the Baptist church — unique because many churches in the Baptist denomination only allow men to be ordained. While Wake Forest Baptist had already left the Southern Baptist Convention and is still not a member today, many Baptist churches in the South are, and they rarely allow women to preach. Fewer Baptist churches even outside the convention allow trans-women to be ministers, and that’s what makes Saunders’ ordination so radical. On March 24, 2019, Saunders became one of the first openly trans woman to be ordained in the Baptist church.

A couple hundred people came to witness this moment in history. Almost her entire class at Wake Forest School of Divinity was there, as well as a few university administrators. Her grandmother and grandfather were there too. They are the only two people from her biological family she’s still in contact with.

While her biological family may have not been there, her church family was. Most of the Wake Forest Baptist congregation came to support Saunders — the 24-year-old Wake Forest Divinity student who became one of their own two years prior when she walked into a church service.

Church of misfit toys

Saunders didn’t even know there was a church that met on campus until a friend told her about a “Trans Day of Remembrance” service in 2017. And he only told her because he helped plan it.

When she heard her friend use “Baptist” and “trans” in the same sentence, Saunders was surprised. She had grown up in Asheboro as an independent fundamentalist Baptist — a conservative tradition disconnected from any formal denomination or convention — that believes being queer is a sin. They interpret Scripture literally and most only read the King James Version of the Bible. Behind the pulpit, there’s a lot of talk about damnation. Women cannot be preachers. Saunders remembers most women staying at home and often being pregnant.

Saunders’ experience in this type of church made her think that welcoming and affirming congregations didn’t exist. When she arrived at divinity school at Wake Forest, she had just come out as trans and was questioning how her lifestyle and faith would ever coexist. Yet, she was learning about all these faith expressions in her classes. So she went searching.

She tried many churches around Winston-Salem, and while they were kind congregations, they just didn’t feel right. Then she went to the Trans Day of Remembrance service.

During the service, Saunders expected to just observe, but then found herself standing up to speak. In tears, she told everyone how freeing it was to finally be herself and live the life God had called her to.

After the service, Lia Scholl, the pastor of Wake Forest Baptist in 2017, introduced herself and told Saunders how moving her words were. She offered Saunders her phone number and invited her to a Sunday service. It took Saunders a couple of months, but she finally gave Scholl a call, and they went for a walk around campus.

As they walked, Saunders told Scholl her story, and it was the first positive experience she ever had with a clergy member.

Then, Saunders finally visited Wake Forest Baptist. That Sunday, Scholl preached on the importance of welcoming trans and gay people, treating immigrants with respect and how everyone deserves to have basic human needs met. It was then that Saunders realized that her faith and her convictions on social justice didn’t have to be separate.

“The people in the pews were very welcoming of me, not only as a trans woman but just as a person,” Saunders remembers. “They were curious about me and wanted to form a real relationship, rather than wagging a finger if I missed church, as it would have been in the church that raised me.”

Saunders came to love this church and the people in its pews, seeing herself as proof of the church’s motto that “all are welcome, no exceptions.”

“I used to affectionately joke about the church as the ‘Island of Misfit Toys,’” Saunders said. “We were all weird or quirky. We had our own things about us that made us not fit in other places, but we really found a home at Wake Forest Baptist. The love in the air was palpable.”

Two years later, the church of misfit toys would be the one to ordain her.

All are welcome, no exceptions

The main part of any ordination service is the two charges — one to the ordained and one to the church.

In her charge, Saunders was asked if she would faithfully serve her congregation through the highs and lows of life while always preaching love and justice.

“With God’s help, I will,” she responded as part of the liturgy.

Next, the Wake Forest Baptist congregation was asked if they would support her through love and prayer.

“With God’s help, we will,” they said. They always had.

After the charges, Saunders knelt before the altar. Those in the audience were invited to lay their hands on her, a typical practice in churches when someone begins vocational ministry. As hands rested on her body, tears streamed down her face.

“I wept through pretty much the entire thing,” Saunders said. “I don’t know why I even bothered to put on makeup that day.”

The ceremony ended with a reception. The people Saunders loved most gathered together to give hugs, eat food and share drinks.

“Not alcohol though,” Saunders recalled. “I did that later.”

Shrinking congregations

Wake Forest Baptist Church is far from the only church to have closed its doors within the past few years. According to a study done by Lifeway, an evangelical research organization, 4,500 churches from across 34 different Protestant denominations closed in 2019 while only 3,000 were started. Compare that to just five years earlier, in 2014, when the number of churches closing and beginning almost equaled each other.

One reason why churches are dying is that people aren’t going to them. For the first time in its eight-decade-long history, Gallup reported that church membership is below 50 percent.

Scott McConnell is the executive director at Lifeway Research who has spent much of his professional life producing studies and analyzing statistics in order to help churches. He likes to remind people that while church operation is largely connected to finances, the survival of churches is truly dependent on the people who are a part of it.

“Churches are people, and when you start to get down to tiny numbers, or the different spiritual gifts aren’t present — if there’s not somebody to teach, there’s not people encouraging, there’s not people serving — then they’re really not functioning like a church,” McConnell said.

Gallup found that church membership is strongly correlated with age. Only 36 percent of millennials belong to a church compared to 66 percent of traditionalists — those born before 1946 — and 58 percent of baby boomers. As these older generations pass away, there are few young people to take their place in the pews.

Wake Forest Baptist reflected this trend of declining membership. At the end of its first year in Winston-Salem, its membership included 380 students and 303 non-students — mostly faculty, staff, administration and their families. In its last year, Lamb said that the average attendance was 25 to 30 people — a majority of them being over 50 and none of them being college students.

Lifeway Research did another study in 2019, this one examining how many young adults (18-22 years old) dropped out of church and why. The study found that 66 percent of respondents dropped out of church for at least a year between the ages of 18 to 22. McConnell says that these statistics and the stories behind them can tell us why young people are dropping out of church.

“The number one reason [why young people stopped going to church] is that they physically moved to a new location and just never found a new church. It simply wasn’t a high-enough priority in their life that when they relocated, they didn’t add that back in,” McConnell said.

If church was something that their parents pressured them to do, college students now found themselves free from that responsibility. Young people also dropped out because they viewed church goers as hypocritical and disagreed with a church’s stance on political issues.

“Theologically, we can step back and condemn [churches] for that. Because the gospel is for everyone, and the heart of every church should be to reach everyone,” McConnell said. “At the same time, we continue to see a pattern that churches tend to be most successful at reaching people like themselves. That’s true socioeconomically, that’s true ethnically, and it’s true age-wise. It would be harder for an older church to truly be welcoming of a completely different age cohort.”

This proved to be true for Wake Forest Baptist, who like many other churches in America, had a hard time attracting young people or even more people at all. At its final service, 37 people came to worship together for the last time.

Let God do the rest

Jerry Gay was 12 years old when he attended the church’s first service in 1956. His family had moved to Winston-Salem from Wake Forest, for his father to teach math at the college. At 78, he was about to attend its last.

Others in attendance hadn’t been to the church in a while but came for the final gathering. People hugged old friends that came through the door. “It’s like a homecoming!” someone said.

Maggie Hurst sat in the back row by herself watching as people chatted. She drove from Statesville that morning to be with the church that ordained her on their last Sunday. She still works in ministry now; however, she said work was hard to come by for a gay Baptist preacher like herself.

That day’s announcements were grim. Lamb said social media sites would disappear in a few weeks. All final donations had to be made by the end of the year, and all the church’s belongings that received bids in the silent auction must be picked up next week.

After a hymn, Lamb led the church in a call-and-response prayer that reflected on the church yesterday, today and tomorrow.

“We lift these names, our church ancestors, who made us feel belonging here,” Lamb prayed.

The congregation called out the names of those who made them feel welcomed here. Sara. Carl. Marcus. Penny. Gene. Warren. Pastor Rayce.

“We lift these emotions stirring inside us as we gather in this space for the last time,” Lamb prayed.

The congregation was invited to name the emotions they were feeling that morning. For several moments, there was silence. No words could do their feelings justice. Eventually, a few people spoke up. Sadness. Hurt. Gratitude. Guilt. Hope for the future.

“We lift our commitment to your work outside of this place,” Lamb prayed.

People shared a next step that God was calling them to take once the church closed. Hurst said she would start a queer Bible study in Statesville.

Next, the congregation sang “Come, Thou Fount of Every Blessing,” and then Lamb delivered the church’s last sermon.

Lamb said that he’d been dreading the last Sunday. He feared that when the end finally came, he wouldn’t know what to say. So he decided to go back to the basics of sermon preparation — a seven-step process he learned in seminary. For his final sermon, he walked through those seven steps.

Step one, pray.

Step two, let the Holy Spirit reveal to you a passage of Scripture.

Lamb said that God often procrastinates on this one, but the Spirit finally led him to 1 Corinthians 2.

Step three, wait for the Holy Spirit to reveal the larger message.

Lamb read verses 1-10, which describe how Paul came to the church in Corinth not with lofty words or mere human wisdom but with the truth of Christ and his crucifixion.

Step four, tell an attention-grabbing story.

He told the story of a mentor who supported him through his depression. His mentor often told him that “When tomorrow comes, you’re going to realize that you’re okay.”

Step five, draw a connection to the passage.

Lamb said that, like Paul, he was also frightened when he came to this church in January. He teared up as he shared how welcoming this congregation was of him and what a joy it had been to lead them.

Step six, proclaim.

Lamb told the congregation that the church isn’t an institution, but rather the people who make it up. He commended them for their testimony to God’s love in the way that they loved this church, this university and this community.

“When tomorrow comes and Wake Forest Baptist no longer exists, it will be okay, and you will be okay,” Lamb said. “Because we are Wake Forest Baptist Church, Wake Forest Baptist will live on.”

“Now for the last step,” Lamb said. “Step seven — let God do the rest.”