Turquoise sleeves and light pink fans danced to the melodic classical Chinese music, as a roll of ink painting unfolded in the Scales Fine Arts Center. At the end of the song, the dancers stopped their movements and bowed elegantly to the audience. The beauty of the dancers and the melody of the song still lingered in the auditorium for a long time. I, as an audience member, felt as if I were in an Eastern wonderland cut off from a Western city.

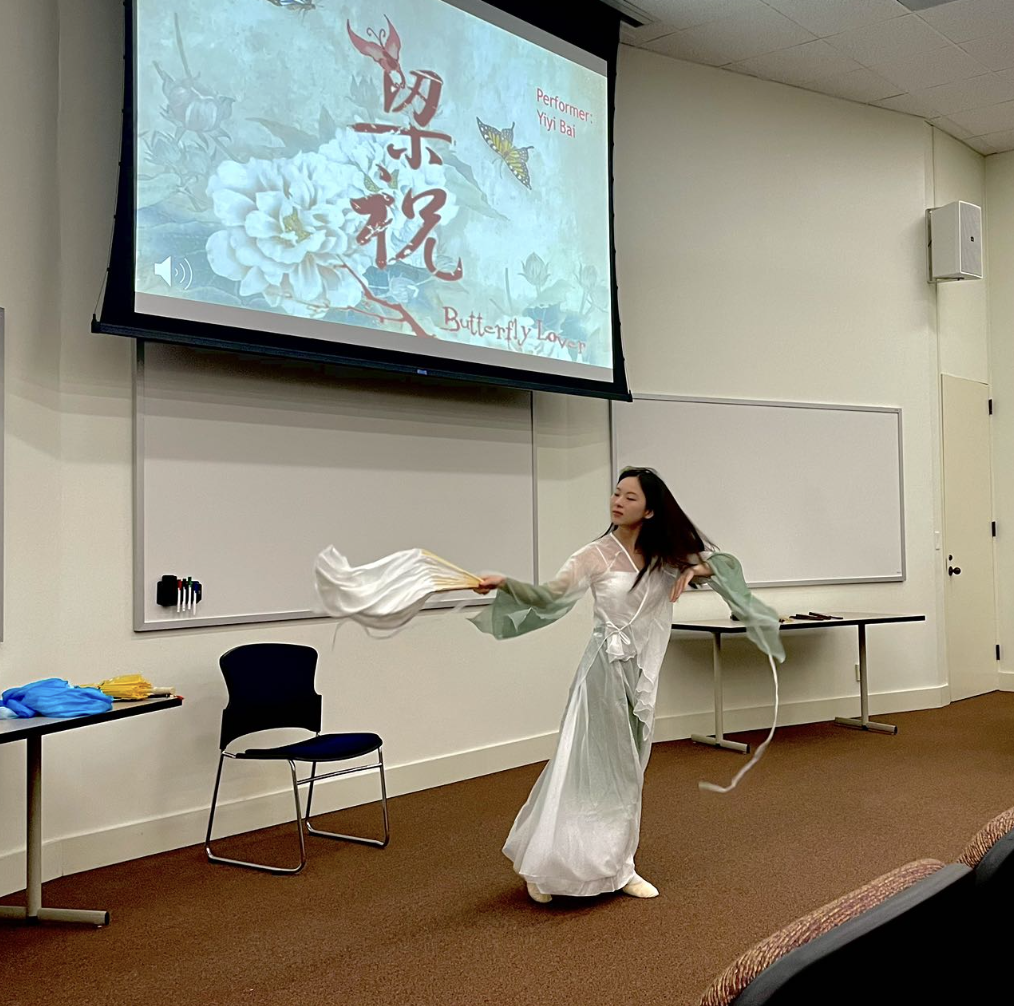

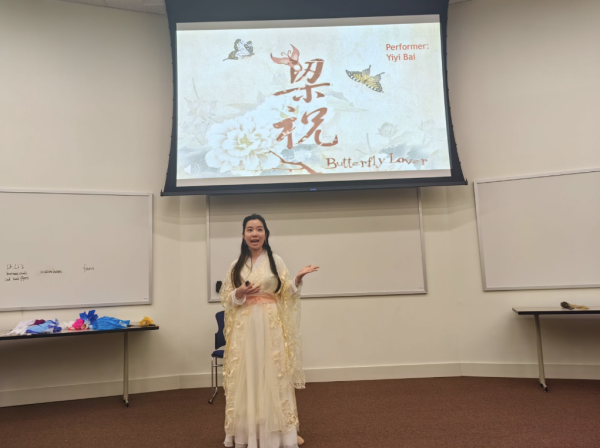

With support from the Wake Forest Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures, professor Melody Li, professor Shu-yu Huang and Yiyi Bai — a freshman dancer — presented an interactive speech to the Wake Forest community on Oct. 26. The event consisted of Chinese dance and opera performances; lectures about the history, props and aesthetics of Chinese dance and opera; as well as the Chinese culture and philosophy behind the choreography.

Li pointed out that China’s vast land with rich history gave birth to many different styles of dance, such as classical dance, martial arts dance, ethnic minority dance and even square dance, which originated as the entertainment of retired women. Ancient Chinese folk stories and the country’s extended cultural history lay the foundation for these dance styles, as well as the shapes and characteristics of the dancers’ costumes and props.

Li and Bai used a Chinese classical dance performance to show the audience how Chinese culture and dance styles intertwine. Li said that traditional Chinese dance steps include many soothing movements of drawing circular shapes in the air. The ideal of a circle represents tolerance and openness, and the dance movement of “drawing circles” reflects this part of Chinese philosophy. Such movements are closely related to Chinese cultural heritage. Chinese culture emphasizes the use of softness to overcome rigidity — using gentle movements to display inner strength.

Li mentioned that the props for Chinese dance, such as water sleeves and fans, play a very important role in conveying the meaning of dance. Dancers can emote through the flexible use of props and achieve a sense of self-extension. The dancers use props to amplify their movements while remaining elegant and restrained, maintaining the breath of the dance and the balance of “qi” (flow) in Taoism.

Softness preserves great energy in Chinese culture. Simplicity and emptiness can also have multiple layers. The true meaning of conforming to the laws of simple and natural flow — “doing nothing to achieve everything,” as the Taoists say — is vividly displayed in Chinese dance.

The presentation of the extension and emptiness also resonated with Huang’s performance.

“If you’ve ever seen Western operas, a lot of the time they can stand still and sing and often come with a variety of gorgeous and complex stage designs and props,” Huang said. “They can then probably start hitting the high notes and ‘show off’ their voice. Chinese opera is not like that.”

According to Huang, Chinese opera stages are minimalist, often consisting only of a table, chair and actor. The storyline relies solely on the actor’s dance moves and vocalizing. Although such a stage looks very empty, this sense of blankness brings richness. It is the simple and constrained setting of the stage that leaves the audience with unlimited imagination.

Because of this, though, the performance of Chinese opera is very difficult. A complete performance requires a skilled actor who can sing through the act while dancing on the big stage. Because of such simple scenes and props, the actors need to stretch more to attract the audience. In addition, the same prop can be compared to many items as the actor sings different passages, so as to achieve a wonderful presentation of the story.

“I think Chinese dance and opera is a good entry point to understand Chinese culture, so I have held such talks on many university campuses,” Li said. “Chinese dance is a language that transcends boundaries of different cultures, and [is] a great way to make me connect to my own culture.”