Junior Enzo Menghini is a double major in philosophy and political science. More than this, though, he is a poet who grew up in São Paulo, Brazil, but he has always felt like the 2005 version of Kurt Vonnegut, the author of “A Man Without a Country.”

“I don’t associate myself with the Brazilian government or anywhere else,” Menghini said. “I like to think of myself as a citizen of the world.”

The incessant struggle to find his own identity is at the heart of Menghini’s life — both as a human and a poet. Despite Portuguese being Menghini’s native tongue, his first meaningful interactions with literature were all with English-speaking authors. When he was younger, a string of surgeries left him with a lot of free time on his hands, which he filled by reading horror novels from authors like Stephen King.

“But then I had this transformation,” Menghini said, “where I started getting more interested in literature itself. So I read [John] Steinbeck’s novels, [Ernest] Hemingway’s short stories and some works by Charles Dickens.”

Menghini has never felt anxiety about reading and writing in an English-speaking tradition, however, because of the long line of South American giants before him who have done so, like Jorge Louis Borges and Fernando Pessoa.

“You sort of understand that you can’t reach that many people if you don’t write in the language that is spoken by the most people in the world,” Menghini said. “The entire function of creative work is to put yourself out there — to have people listen to it.”

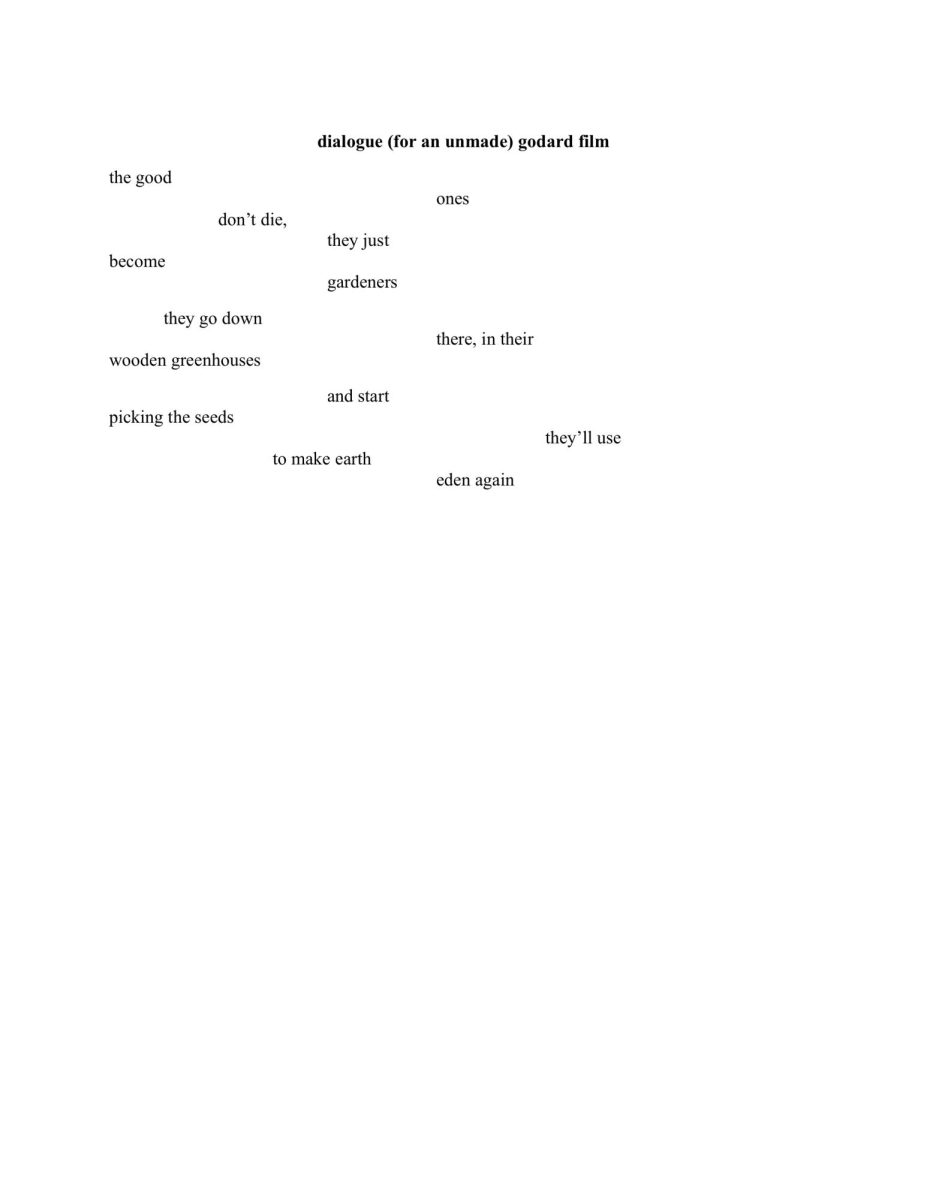

In more recent years, Menghini has found inspiration in South America’s particular strain of magical realism as well as modern poetry. He loves tango music, French new-wave cinema, Cormac McCarthy and stand-up comedy. His myriad of inspirations collide explosively in his poems, often resulting in work that is strikingly fragmented, both visually and ontologically. This is a reflection of his own interiority but also, he says, a product of human nature.

“The human being, at the end of the day, is just a fragmentation,” Menghini said. “We don’t have a complete self. Literature is the struggle to create a unified whole or unified aesthetic.”

With his most recent batch of poems, Menghini believes that he is beginning to find his unique voice. This tremendous growth as an artist might be borne more out of necessity than anything else. Over the summer, amid emphatic rambles about literature and religion, I asked Menghini why he feels compelled to write.

“I write because I figured out this year that I don’t belong anywhere and can’t belong anywhere except in paper,” Menghini said.

Over the past year, Menghini’s writings have evolved from belletristic experiments into emotionally charged pockets of philosophical sophistication. They are intentionally deceptive in their simplicity, inviting more nuanced readings for those who are willing to look closely. More than anything, they reflect a young, bold and confrontational poet. A poet who wields words like shattered glass.

Below, I have selected five of Menghini’s poems out of a collection of over 30 that Menghini hopes to publish in the near future. I believe that “dialogue (for an unmade) godard film,” “kurt vonnegut’s assessment (in a liberal talk show),” “argentinean (weeping guitar melody),” “78th dream song” and “whitman be praised” go a long way in capturing the incredible range of Menghini’s poetic capability.