A year ago, my grandfather suffered cardiac arrest after contracting COVID-19. He found himself in the hospital, and I found myself on I-40 East, heading home to see him for the last time.

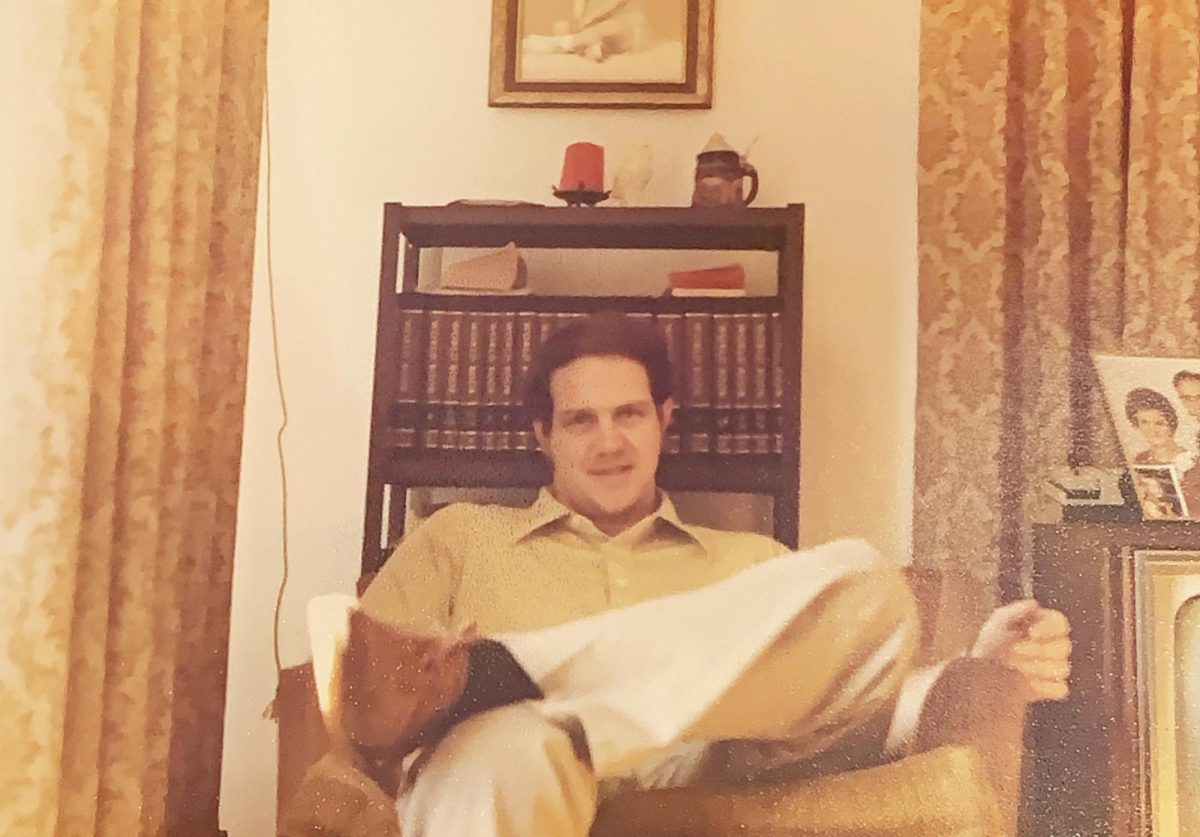

My grandfather had never been healthy — bound to vices like tobacco in his old age. He was never one for vegetables or exercise, but what he lacked in health, he made up for in resilience. He’d been to the hospital many times before and had always come home.

After getting my visitor name tag from the hospital receptionist, I rode the elevator to the cardiovascular floor. A nurse met me in the hallway and decked me out in PPE — gloves, a gown and an N-95 mask.

His body was in the hospital room, but I sensed his spirit was elsewhere. Life on earth had been a passage, and he was nearing home.

I was physically in the room too, but my mind was elsewhere, soaring through the past. I thought of all my memories with him. All the text messages. All the phone calls he’d made. All the phone calls I could have made. All the voicemails he’d left because sometimes I’d be too busy to pick up. I laughed under my N95 mask when I remembered how he’d always sign his text messages with “Papa Mike” as if I didn’t know who was texting me. He didn’t understand iPhone contacts.

My visit with him was strange. It was not unlike any other conversation I had had with him before, but I could feel this one was different. It had weight.

He was visibly weak and could barely ask me questions. I could hardly answer because I was choking back tears.

What was there to say?

***

My grandfather was a storyteller. He always joked with me that I should put his stories in “my paper.” What he meant was this newspaper, the Old Gold & Black, of which I was news editor during the last few months he was alive. I know he’d be proud to see my name at the top of the masthead with his story finally in the paper — the last paper I’ll ever put out as editor-in-chief.

He was an early influence on my love for writing. While my parents were working full time, he often watched me and my siblings after school and during the summer. He surrounded us with stories.

He had one of those car DVD players that could be strapped to the back of the front seats. He would record Scooby-Doo episodes with his camcorder and burn them on DVDs, so we could watch shows on our drive home. Looking back, I realize how funny this was. The drive was not long, and we weren’t rowdy kids. There was no need to keep us entertained like that. I think he liked hearing us laugh at the characters and gasp as the mysteries unfolded, and I think, secretly, he enjoyed them, too.

For an afternoon snack, he’d pop Hot Pockets in the oven, and we’d listen to him tell stories of growing up poor in rural West Virginia.

My grandfather was the ninth of his parent’s 10 children. He grew up in Van, which is one of those towns with people that could make it feel larger than it was. In 2020, its population was 138. There are university lecture classes larger than that.

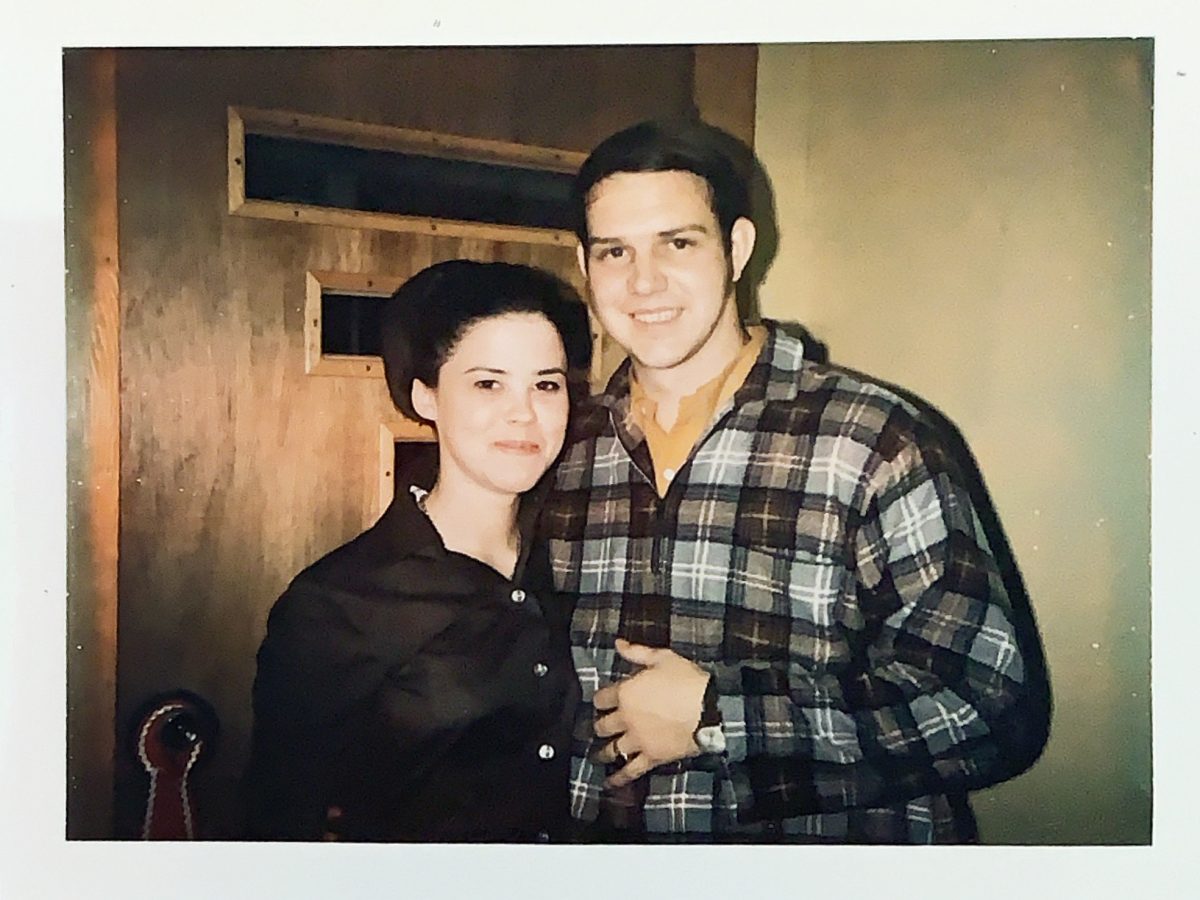

He told stories of playing in the mountains with his brothers. He told stories of his dad working in the coal mines. He told us about moving to North Carolina and meeting Margaret, the woman who’d become his wife and my grandmother. He told scary stories, funny stories and serious ones too. Most of them existed somewhere between fact and fiction, and the fun of it was discerning which was which. His stories commanded our attention, and his imagination never diminished.

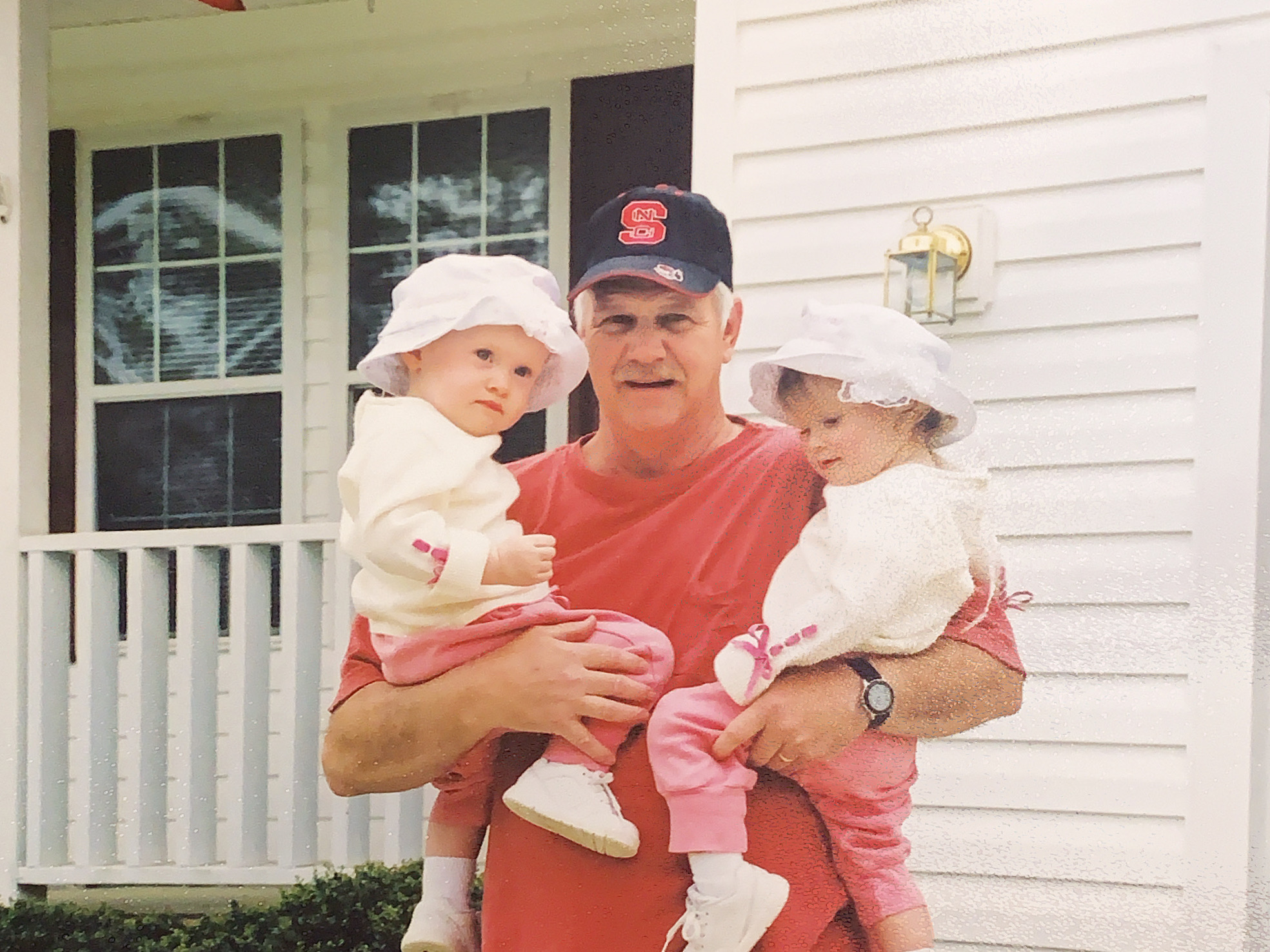

My grandfather also told stories with his camcorder, which he used to do more than just record television shows. From infancy to high school, he captured his grandkids’ upbringing, so we could watch our memories, as well as his.

I grew up in the middle of nowhere in Knightdale, N.C., which meant I had way more fun than “neighborhood kids.” My siblings and I rode bikes through the woods. We went fishing. We played basketball and turned our driveway into PNC Arena. We’d go on golf cart adventures. And my grandfather was there, recording it all. He’d ask us interview questions and make us feel like movie stars.

What my grandpa was trying to do, I think, was remember. He passed down his West Virginia stories to preserve them. He also wanted us to know where he came from — how hard he had worked to raise a daughter smart enough to build a career in accounting so she could provide for three children — his grandchildren — who would go on to be some of the first in our family to earn Bachelor’s degrees.

Today, a box of these videos sits in my parents’ living room. When we are all home, we like to play one and marvel at how much has changed. We notice small things like how the kitchen is painted a different color now. Or how ugly my bobbed haircut at age nine looked. And how we all were so much younger.

We also notice big things. Like how bits of our childhood attitudes gave way to our adult personalities. I was loud. Strong-willed. Independent. A little bossy. I’ve hopefully mellowed out since then, but many of my interests remain. One video shows me running around the house with a notebook interviewing my family members. I still love to ask questions.

***

I recently watched a short documentary film by Jay Rosenblatt called “How Do You Measure A Year?” The film is a compilation of video footage that Rosenblatt took of his daughter every year on her birthday from age two to 18. He asks her simple questions like “What are your favorite things in life right now?” as well as more complex questions like “What is power?” Her answers show how her opinions and circumstances shift, documenting how she’s changed over 16 years.

The documentary’s title is inspired by the song “Seasons of Love” from the musical “Rent.” The lyrics go like this:

“Five hundred, twenty-five thousand, six hundred minutes

How do you measure, measure a year?

In daylights, in sunsets

In midnights, in cups of coffee

In inches, in miles

In laughter, in strife”

This song strikes me because years are composed of the little things — the sunsets, the cups of coffee, the inches. People tend to forget the little things unless they’re documented.

There’s a few home videos that are difficult for me to watch. My grandpa is recording and trying to ask me questions, and I brush him off. At six years old, I was much more interested in watching my television show or playing with my dollhouse than talking with my grandpa. Sometimes, the videos got old, and we all grew a little annoyed. Little did I know, those videos would mean so much to me one day. When we miss him, we can play the DVD and hear his deep laugh once again. The videos give us our memories back.

The videos also help me remember what formed me. The afternoons eating Hot Pockets, watching cartoons and listening to my grandfather’s stories made me who I am, year after year.

Toward the end, the song asks, “How can you measure the life of a woman or a man?” The song’s answer?

In truths that she learned

Or in times that he cried

In bridges he burned

Or the way that she died

***

A few days after that hospital visit, my mom called me. She was in the hospital room with my grandfather as he was slipping away. She put the phone on speaker, put it near his ear and told me to say goodbye. Here had come the moment to say the last thing I’d ever say to a man who had meant so much to me.

“Thank you,” I said.

It felt like a shallow response. I had said “thank you” to the barista who made my coffee that morning and to the stranger who held the door open.

But what was there to say?

Even “I love you” felt insufficient. People say they love their favorite foods and their best friends. They say “love you” to horrible boyfriends and their parents, all the same.

I wanted to make sure he knew that I was thankful for him. That he changed me — for the better. That he gave me a love for storytelling. That he taught me how important it is to remember.

Perhaps our gratitude to a person lies not in what we say to them in a moment, for a moment is too fleeting to encompass a lifetime. It’s not what we say, but rather it’s in understanding what they’ve been saying all along.

Thinking back to that last conversation I had with my grandfather, the one in the hospital that felt so strange, I believe I told him everything I needed to say.

“How’s school?” he said.

“Hard, but good,” I said.

“You still writing?”

“Yes, papa. Still writing.”

Dianne Green • Dec 8, 2023 at 3:25 pm

Your wonderful words of life express the warm gratitude you had for Papa Mike. I had the pleasure of making his acquaintance only once but what an awesome impression he made on me. What a wonderful memoir he left to all of you — his blessed grandchildren. We never know what we have until it is gone but Papa Mike left his memory to all of you to enjoy and share with your children. Thank you for writing this article about a Papa who would have been very proud of the way you told his story. Now, I am going to get my kleenexes because it has truly touched my heart!

Teresa Spell • Dec 4, 2023 at 8:57 pm

Oh Christa, this is so beautiful and your Papa Mike would love it! If you can, I would love to have a copy of this article for my family history book. Your Aunt Ruby would be so proud of you too!! Love your cousin, Teresa

Allen White • Dec 4, 2023 at 12:48 am

Thank you, Christa, for a wonderful tribute to your grandfather and my big brother. When I was about eleven or twelve, Mike told me that our hometown of Van was named after Rip Van Winkle. He then pointed to one of the mountains that surrounded our house and said, “That’s the hill right there where he fell asleep for twenty years.” I believed him until I mentioned it to one of my teachers in high school and she looked at me like I had just sprouted mule ears out of my head. I was fourteen when I moved to North Carolina, but Mike had been here for a year or more. Down in the valleys and up in the hollers of Boone County, West Virginia, we didn’t have a whole lot of sky, so I was particularly taken by the big blue one down here and all the puffy white clouds. Mike caught me looking upward and daydreaming one afternoon and asked me, “What are you looking for?” I told him I was just admiring the clouds and he told me, “People come from all over the world to see the clouds in North Carolina, Dee. Big tourist attraction.” Again, I ate it up like it was cotton candy. It was years later when I figured out he’d got me with that one, too. I think Mike shared his storytelling trait with both of us, Christa. You certainly have the gift and I pray you will keep sharing it. I enjoy all your writing immensely, and I know many others do, also. Love ya, kid!

White Brian • Dec 1, 2023 at 7:40 pm

Wow! What a beautiful story of my dads affect on such a beautiful and wonderful niece. Thank you so much for writing this and letting everyone know how much my dad was loved and appreciated. I know he is walking the streets of Gold right now, telling somebody some very funny stories! Love you. Uncle Brian

Tina • Dec 1, 2023 at 7:15 am

Thank you for sharing your heart with us all in this beautiful and wonderfully written story. Your Papa Mike was pretty amazing and so are you!

Kim Humphrey • Dec 1, 2023 at 12:39 am

Beautiful memories of Papa Mike. I recall him always at your games and events and always recording them. What a treasure he left behind. Proud of you, Christa.

Rex White • Nov 30, 2023 at 10:05 pm

Thanks Christa, for those wonderful memories of a man, a father, a Grandfather and a wonderful brother who meant so much to everyone’s life he touched! He is greatly missed, but we are blessed and comforted to know that he is with the king and pain-free looking down on us. Love you, Rex & Tricia

Amy Richards • Nov 30, 2023 at 9:33 pm

Thanks so much for sharing all these memories! Brings back memories of your mom and Brian at our house many years ago. Hope you and your family have a very Merry Christmas!

Jan and Ranny Hyatt • Nov 30, 2023 at 8:35 pm

Such a wonderful commemoration of a special relationship between grandparents and grandchildren. Papa Mike will live on in loving and humorous memories just like he wanted. Thank you Christa.

Margaret White • Nov 30, 2023 at 7:35 pm

Love the article. Papa Mike was always proud of you and your writing. Thank you for the memories. Love you. Mimi