Recently, the question of when, how and whether institutions of higher education (IHEs) should respond to both domestic and international crises — especially those that have little to do with their core education missions — has come to the forefront of national discourse. Today, international conflicts abound, with the most notable being those in Europe and the Middle East. But there are other issue areas like the Armenian-Azerbajaini conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh and the Myanmar Civil War, where thousands have been killed in ethnic conflict, that get no attention from university presidents.

Why are some crises deserving of a statement of support and others not?

Wake Forest has a recorded, yet inconsistent history of commenting publicly on domestic and international issues beyond the two most recent crises. Former Wake Forest President Dr. Nathan Hatch openly discussed the Haitian earthquake in 2010 and the Atlanta mass shooting that targeted Asian Americans in a time of rising hate. The latter statement even took a stance on “gender violence.” Yet Hatch did not opine on all such events. For example,Wake Forest released no statement on the San Bernandino shooting in 2015 that killed 16 people. Half of that total were killed in Atlanta.

When it comes to statements, arbitrary decision-making opens the door for confusion on when, how and why schools comment on issues outside of their educational mandate. Clarity and consistency on this topic of public university statements are of paramount importance. Schools must adopt and make known a position of neutrality on political issues.

The decision to release a statement at all seems less than systematic. Wake Forest, along with the vast majority of IHEs, seems to struggle here. If it cannot, or will not, refrain from making statements on issues that may be captured by inclusive mottos like “For Humanity,” but fall outside of its core educational mandate, transparency is the best alternative. The school would do well to establish and publicize criteria for their public pronouncements so students, staff, faculty, administrators and parents can know how Wake Forest sees its role in the rhetorical ecosystem of higher education and public crises.

The decision to make a statement is inherently political. As a result, there will be those who advocate for the university to refrain from commenting on all crises because it is difficult to establish a clear definition of when a statement deserves release. The Kalven Report, drafted at the University of Chicago in 1967, recommends that universities not adopt a “collective position” on “political or social” topics. But that does not mean that universities cannot offer messages of generic support to impacted individuals within the campus community. The University of Chicago itself sent out messages to students in the wake of Hamas’s attacks offering resources and guidance in light of the conflict. The university, therefore, must determine what statement adequately balances student need and institutional neutrality.

Crafting a public statement that satisfies involved parties while maintaining the university’s reputation is critical and difficult. Taking a stand on any isolated issue is inherently risky. Antisemitism and Islamophobia have both risen as the Israel-Hamas war rages on. Statements that mention one without the other have been seen in the past as the university taking sides. The unavoidable reality is that any incomprehensive stance will be incongruent with a faction of the administrative, faculty or student body’s opinions, and effectively censure minority voices. All schools must take immense care in ensuring their speech does not limit that of others.

Wake Forest’s recent statements have been a mixed bag. On Oct. 10, the school released a short statement calling all violent acts “an affront to our shared humanity.” On Oct. 16, Wake Forest expressly condemned all terroristic and violent acts. But as the infamous motto says, “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” Since Wake Forest has no way to confirm that all members of the campus community favor their expressed view, it should refrain from taking any stance on this war and others ongoing or in the future. Instead, all statements should center community members’ well-being and offer resources for support, as Wake Forest stated on Oct. 10, and continue to promote long-held tenets of academic freedom and free expression, as Wake Forest stated on Oct. 16.

Stated plainly, my advice to IHEs is this: Commit to institutional neutrality officially and publicly. Do not attempt to appease all viewpoints or with lengthy refrains on all the various forms of hate that exist. It is a thankless, impossible task. It is preferable to avoid such topics altogether. Short-and-sweet boilerplate statements will anger those who believe the university must take a stand on the issue du jour in the world. But they are essential to managing public expectations the next time a crisis strikes and the administration debates how to respond.

With the previous structure in place for all public statements on public affairs, the task of deciding whether to comment at all becomes simplified. It is still preferable that schools prioritize silence, because the more a school speaks out, the more likely it is that internal debate is stifled and external criticism is raised. But if schools limit their statements to community well-being and refuse to take a stand, they should feel more comfortable in releasing comments on issues that impact students, faculty or administrators. Of course, education issues are political issues too, and pose problems regarding the question of public comment. As the Kalven Report argues, though, schools have a right to respond to social issues that “threaten the very mission of the university and its values of free inquiry.” Only within these limited parameters should IHEs take public stances on the social and political problems of the day.

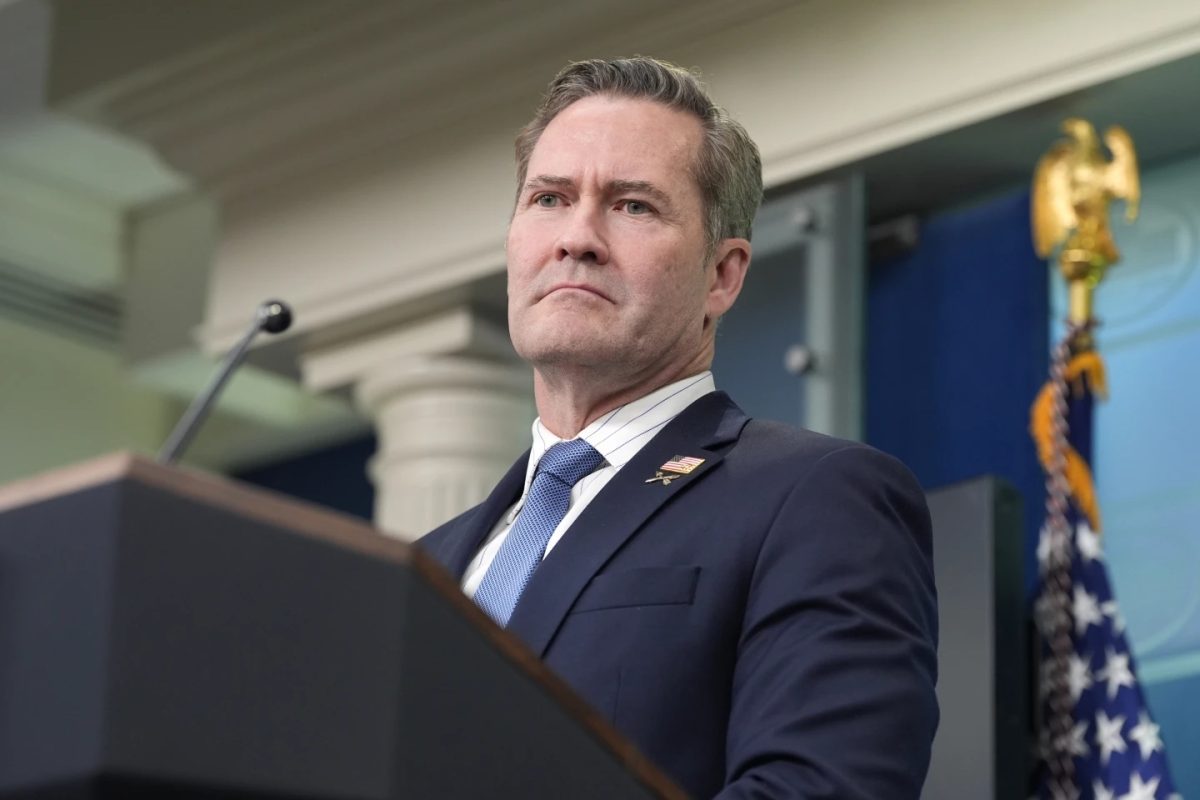

When schools routinely promote value judgements rather than community support, they run the risk of outrage. Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia sent out an email on Oct. 8 — the day after Hamas’s terror attacks — condemning the violence in Israel and offering support to impacted members of the community. In an Oct. 20 editorial, the Georgetown Voice, an independent university news magazine, condemned the first statement for reducing Palestinians to terrorists — which it did not — and for not contextualizing Hamas’s terrorism — which it did not and should not. In this example, a relatively political statement, meaning one in which the deaths of only one side were acknowledged, was criticized for not being expressly political enough, albeit in the other, correct direction.

Yet even neutral statements, such as those made by Stanford University, faced pushback from “dozens of faculty [who] signed a letter demanding ‘unambiguous condemnation’ of the Hamas attacks.”

This advice, therefore, is not a panacea, and following it will not pacify all who have vested interests in making sure the university speaks the way they want it to. But it does provide the best balance between the values of the university, its campus community, and the outside world. Schools are too often paralyzed and confused by community demands on their public responses to crises. But they do not have to be. By committing to a policy of transparency in deciding when the university comments and brief neutrality in deciding how they comment, universities put themselves on a path to long-term public relations success.

These crises revolve around theories that have no clear answers, and gray value judgments sit uneasily in a world divided, engrossed in black-and-white thinking. Is violence against civilians ever justified? Is Russia exercising legitimate claims to historical lands? Ultimately, IHEs should have little to say on these topics. For the sake of the university, these are questions for professors, not presidents, to answer.

Update Dec. 1: A typo was removed from the subhead.

G • Jan 2, 2024 at 3:21 pm

This is a good article. One point of contention, while Hatch and many others characterized the Atlanta massage shooting as racially motivated, there is no evidence to back that up. The shooter was a deranged conflicted religious sex addict. The victims race had nothing to do with it. There-in lies the danger of selective outrage. “Maladjusted socially-outcast male turns to violence” is not as politically potent of a narrative as “Trump is turning white men into racist murderers”.

Anonymous • Dec 9, 2023 at 9:36 am

As it relates to the Hamas attack on innocent Israeli citizens, Wake Forest should have condemned the attack without equivocation.

Jen • Dec 8, 2023 at 8:55 pm

Wake Forest should have condemned the attack on Israel without equivocation.

Oliver Miller • Dec 1, 2023 at 3:09 pm

I understand your argument, and part of me agrees with it. But I wonder whether a position of neutrality in the face of genuinely abominable issues that reverberate through our collective consciousness is amoral.

Ari • Dec 1, 2023 at 12:33 pm

Wow, Jacob Graff is a very talented and interesting writer. I hope we hear more from him.