At Wake Forest and universities across the nation, students are fighting an unprecedented battle with mental health struggles, and faculty are often the first line of defense.

“Often a student first shares with their faculty person,” Warrenetta Mann, assistant vice president for health and wellbeing at Wake Forest, said. “Students care a lot about their academics here, so [for] anything that negatively affects academics — or even has the potential to — a student is likely to go to [their] faculty person and say, ‘Hey, you just need to know that this thing is going on.’”

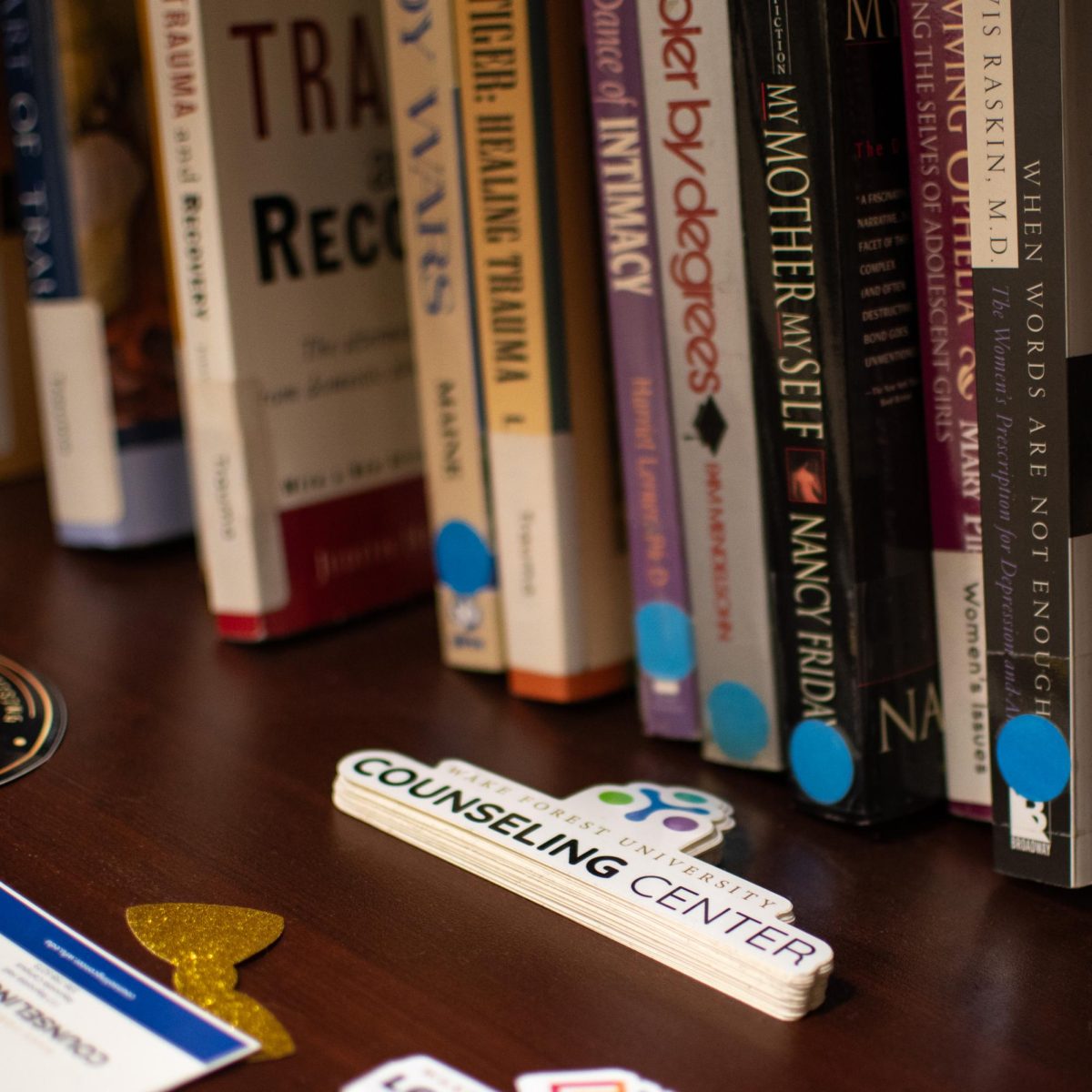

According to Matt Clifford, Wake Forest’s interim dean of students, faculty and staff are the primary referral source to Wake Forest’s CARE case management team, which reviews referrals submitted by students, faculty and staff when they are concerned for their own wellbeing or the wellbeing of a friend. The referral is then reviewed by a case manager who connects them to the appropriate campus resource, like the Counseling Center or Safe Office.

The university does not require faculty to attend trainings but offers optional sessions such as Care 101, a training series that includes a 1.5-hour in-person session, a one-hour online session and access to a resource workbook. Mann and Clifford both agree that requiring training would be difficult, as it would add to professors’ already busy workloads. Still, they want to equip faculty with the tools they need to help students.

“We want to make sure that faculty don’t feel like they’re left alone to figure out how to respond in the right way,” Mann said.

According to Mann, 18 faculty and staff members were trained at the beginning of this year to be ambassadors who will host their own mental health care training sessions this semester.

Clifford said that the University’s philosophy is to create a culture where faculty care enough to learn how to recognize and respond on their own to mental distress in their students.

“What we find is that a lot of our faculty voluntarily are very engaged in not only mental health things but the Alcohol and Other Drugs Coalition and other coalitions on campus to address specific issues,” Mann said.

Mann said that Wake Forest takes a concentric circles approach when it comes to mental health training.

“The people who really care will come to all the trainings, and then they’ll go back to their departments, and it’ll rub off on some of the other people, and then that’ll rub off on some other people,” she said.

Meredith Farmer is an associate professor of core literature at Wake Forest who has taught at Wake Forest for 11 years. She said she often receives anxious emails from students, and it is not uncommon for students to show up to her office crying, often about an issue in another class.

“Students are absolutely struggling,” she said.

Across campus, in the Department of Health and Exercise Science, Abbie Wrights teaches a required course for first-year students called HES 100: Lifestyles and Health. She said that she has frequent conversations with students outside of class about their mental health, but her students are not all experiencing crises.

Wrights said that signs of mental distress in students can be summarized into three categories: actions, appearance and academics. With a front-row seat to how poor mental health is affecting students in her classroom, Wrights knows the telltale signs — not coming to class, diminished quality of work or communicating hopelessness in their assignments.

“I feel like we’re on the front line,” Professor Crystal Dixon, who also teaches a HES 100 course, said.

Without required training, faculty can decide how they will practically address the current mental health epidemic in their classroom. Many professors look for ways they can minimize stress during class time. Wrights decides not to cold call. Farmer does not require students to explain their absences and offers extensions when students need them.

Wrights, Farmer, Dixon and other professors at Wake Forest are all aware they are not licensed mental health professionals but view themselves as liaisons to campus resources.

“We have a responsibility to at least refer students,” Dixon said. “I don’t think we have to be the solution — I think we should always have someone that we can hand off [to].”

This article is part of the Mental Health Collaborative, a project completed by nine North Carolina college newsroom to cover mental health issues in their communities. To read more stories about mental health, explore the interactive project developed specifically for this collaborative.