International diplomacy decisions are made in a constantly evolving world with infinite cultural, political and economic differences across societies. Calculating answers to problems requires attention to every detail, and our diplomats are aware of most of them.

What if we are overlooking one? Well, we are — and you guessed correctly: religion.

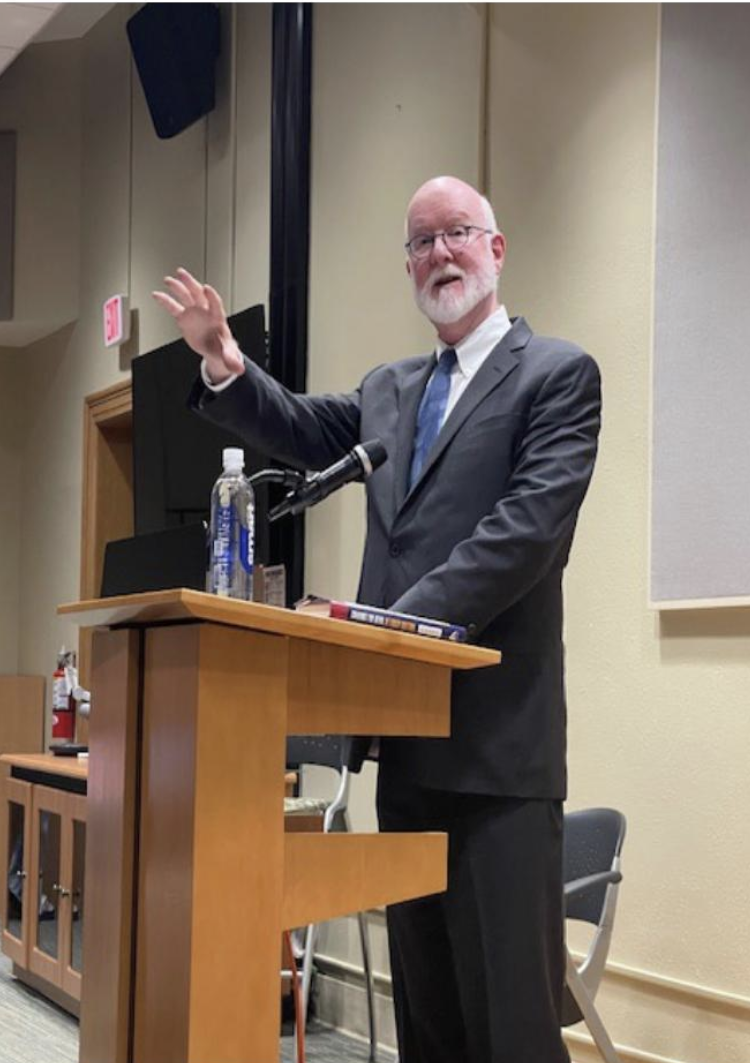

In my interview with Dr. Shaun Casey, former special representative for Religion and Global Affairs at the U.S. Department of State, we explored how religious studies intertwine with diplomacy, different administrations’ actions, Wake Forest’s relationship with religion, and the importance of religious studies in academia as a whole.

Untapped resources

On Feb. 20, 2024, the Wake Forest Department for the Study of Religions hosted Dr. Casey. He was selected by former Secretary of State John Kerry and the Obama administration to lead the new Office of Religion and Global Affairs and to serve as an advisor on all diplomatic matters relating to religion, serving from 2013 to 2017. His office represented the first significant intelligence network focused on religion that directly supported our diplomatic efforts.

Casey and his team had provided religious expertise to American embassies and consulates that guided well-informed, successful international diplomacy.

Following the elimination of the Office of Religion and Global Affairs office during the Trump administration, Casey published his novel, “Chasing the Devil at Foggy Bottom: The Future of Religion in American Diplomacy,” to tell the story of religious studies in global politics.

The Biden Administration has not reinstated his office, which was introduced while President Biden was vice president. To be absolutely clear, they should.

From conflicts to new international partnerships, understanding religious complexities requires expertise. We have access to tested, proven and highly skilled religious experts. Any reason for not taking advantage of these resources is unjustifiable in comparison with the benefits of religious knowledge in diplomatic decisions. In reading Dr. Casey’s book, hearing his speech, and addressing him personally, I can say this:

Our government needs to prioritize understanding religious dynamics in their decision-making, no excuses.

Fighting for accountability

In his novel, Casey presents the ultimate case study of a diplomatic decision that lacked religious understanding: the Iraq War. The United States’ decision to invade resulted in over 900,000 deaths and has cost our nation $8 trillion. To explain President Bush’s significant oversights, Casey cites the leadership differences between a “fox” and a “hedgehog.”

In every organization of leaders, there are hedgehogs. They approach decisions with a single vision, using any means necessary to bring that vision into reality. On the other hand, foxes possess a “breadth of knowledge,” as Casey puts it, able to draw their views and decisions from many different perspectives.

The distinction between the two is found in how each reaches their decisions: knowledge. A hedgehog’s deep knowledge of one line of thinking can have advantages over the fox’s skeptical, broadly informed views. According to Casey, President Bush was a hedgehog pursuing a single vision, with little knowledge of the crucial religious and cultural aspects of the Middle East. With expertise in regional religious dynamics, President Bush’s decisions would have been more informed — possibly changing the detrimental outcomes of the War. This collapse of judgment is not the only example of decisions lacking religious understanding. Take the Cold War.

Scholars have analyzed the true reasons for the collapse of the Soviet Union, which contradict the initial ideological explanations for the conflict as capitalism and communism. Now, we see that religious tensions — across what is now Armenia and Azerbaijan, and Chechnya — were largely responsible for Cold War conflicts, yet were not taken seriously. In the Iraq War, the Cold War, and several other international conflicts in recent history, religious understanding would have aided in de-escalation and possibly prevented conflicts altogether. The results speak for themselves — we need to accept that every hedgehog must have a den of foxes ready to scrutinize and inform their decisions.

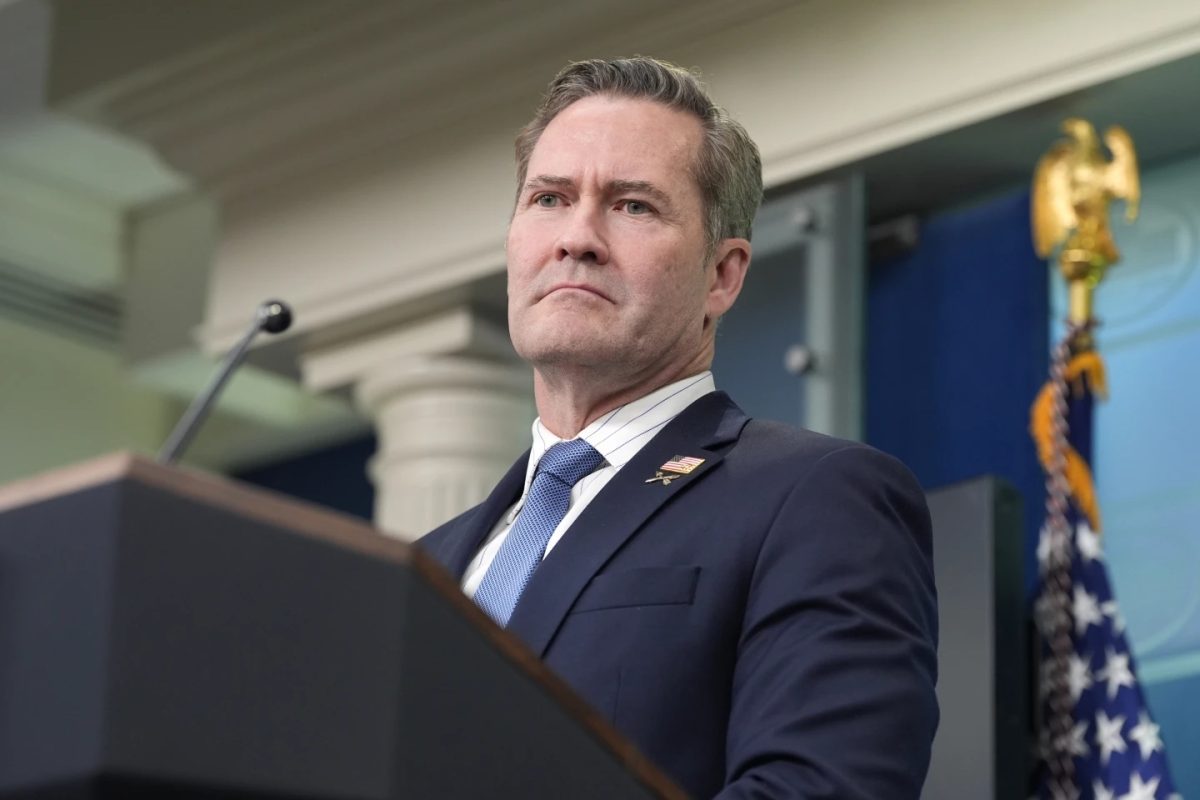

During our interview, I asked Casey for his views on the Biden administration’s diplomatic leadership. Specifically, I asked if he saw a balance between hedgehogs and foxes. His response was insightful, and he echoed the stance during his speech. The secretary of state, in Casey’s experience, cannot know every single international event occurring at all times; however, “what they should have, at the other end of the telephone, is somebody who can answer their questions about religion in any zip code in the world.” The Office of Religion and Global Affairs, led by Casey under the Obama administration, provided just that.

Although the Biden administration has not reinstated Casey’s office, there is little doubt that the Russia-Ukraine war and Israel-Hamas war may have been remedied more effectively with the support of the Office of Religion and Global Affairs. Even where religion may seem irrelevant, Casey has identified how sensitivity to religious tensions is vital to accurately assessing these crises.

Unbeknownst to many Americans, Putin has given several since-deleted speeches that always include a call to restore greater Russia. A religiously tone-deaf government may miss the undertones of the Russian Orthodox Church in his speeches, but Casey did not.

“Why not take a leader at his or her word when they say that they’re doing this in part to restore some form of glory to their national religion?” Casey said. There are obvious influences of religion in conflicts, such as the Israel-Hamas war, but religion can be hidden in less obvious situations.

Without Casey and his den of foxes to advise on religious dynamics in global contexts, how are we to know if our diplomatic decisions are truly well-informed?

A student’s takeaway

When I asked Casey what academia could learn from his approach to elevating religious studies in foreign policy and applying it to education, his response was blunt: “Ignorance of religious dynamics can lead to cascading disasters.”

While the value of religious studies in higher education can be difficult to understand, Casey’s success in bringing religious studies to the forefront of our federal government proves its importance. The ability to understand and research religious undertones in society strengthens individuals across every discipline.

“The ability to interpret religion also makes you a better interpreter of other disciplines […],” Casey said, regarding the inclusion of religious studies in Wake Forest University curriculum. “To be a well-educated human being and citizen in the United States, an ability to grasp and interpret religion and all of its complexity is an asset to that person as a citizen of a liberal democracy,” Casey said.

So, what can students take away from Casey’s teachings and the broader role of religion in diplomacy?

The complexity.

Religion is embedded in foreign affairs in ways that we do not understand, adding even more dimensions to current conflicts around the world. Just from Casey’s anecdotes of addressing crises in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ukraine and Cuba and advising directly on diplomatic relations with the Vatican, Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Palestine, we can see the depth of knowledge and experience necessary to interpret religion in cultures around the world.

For students, our jobs will not require graduate-level religious knowledge, but as Casey teaches, our lives will demand literacy in religion as a whole, and the ability to understand the many ways religion manifests in society.

Casey’s tireless work and eventual success in integrating religious understanding and foreign policy will not be forgotten. Without a doubt, the scholarly community, international community and Wake Forest community recognize the value of people like Casey.

Those who hear Casey’s story will learn that the wisdom of a den of foxes is crucial to guiding the hedgehog that we know as the United States of America.

Afterword

Dr. Casey is the second speaker in the Yeazel Speaker Series that was established by Wake Forest alumni Melissa and Bryan Yeazel, who graduated in 1997. Bryan graduated with a double major in religious studies and political science while Melissa graduated with a mathematics major.

This event was made available to students, faculty and staff who filled the auditorium to hear Casey’s insight and to take advantage of the opportunity generously provided by the Yeazel family. The discussion that Casey fostered and the opportunity for a one-on-one interview is yet another example of the exposure to religious studies that Wake Forest University prioritizes.

Thanks to the hard work of the Department for the Study of Religions, the generosity of community members like the Yeazel family and the institutional focus on religion from Wake Forest, the work of religious scholars will not go unnoticed.