“Founders Vision: The Private Collection of Barbara Babcock Millhouse,” which opened on Aug. 24 and will remain through Christmas Eve at the Reynolda House Museum, begins with some of the biggest names in the history of American art. A portrait of Countess Laura Spinola Nunez del Castillo by John Singer Sargent; a dazzlingly warm New Mexico landscape by Georgia O’Keefe; a shimmering clapboard house in Cape Cod by Edward Hopper — these are some of the defining works that will immediately jump out to both casual and enthusiastic critics. They also constitute, decidedly, the minority component of the collection.

Overall, the private collection of the granddaughter of Katherine and R.J. Reynolds is less concerned with the reputation of an artist or artwork than the Reynolda House Museum in general. Instead of focusing on public value, “personal inspiration and a marked audacity guided [Millhouse’s] choices.” Still, the collection goes a long way in capturing the avant-garde American art scene following World War II, touting a wide range of post-modern paintings from Hans Hoffman to Roger Brown. She was initially afforded this great immersion in the post-war American art scene because her schooling placed her right at its epicenter — Millhouse studied art history at Smith College and interior design at Parsons School of Design in New York City. She was still in her student years when she bought “Fire Picnic” from her friend William Scharf in 1956, one of the earliest major pieces on display.

In her twenties, Millhouse was trying to find her artistic vision at a time when American art was unsure of its direction. According to Millhouse, the questions of the future were aimed at abstraction: “The public, myself included, was mystified by Abstract Expressionism. Was it a joke or was it serious? Were these artists pulling something over on us or did they have something profound to say?” She seemed to lean toward the latter, as her first two major purchases in 1957 and 1958, “Fire Picnic” and “Winter Willows,” were far removed from the realism or traces of realism still evident in the high art of the 1920s or 30s.

Abstract Expressionism seemed to be an exciting step forward for art, but for potential buyers, it carried the risk of professional and personal consequences, something that Millhouse was always conscious of. In reference to “Fire Picnic,” Millhouse said, “Although the projection of Communist threat into this painting is difficult to understand today, it was very troubling for me at age 22, but I learned that a work of art can exert a tremendous power and arouse intense feelings. It was a long time before I dared look at contemporary art again.”

Indeed, the overwhelming majority of paintings displayed in the exhibition were purchased in the 1980s or later, when it was much more acceptable to champion art that subverted traditional regimes of seeing and meaning-making. In short, the surrealists, the cubists and the expressionists were already a thing of the past, sterilized. But there still remained the practice, as Millhouse put it, of organizing the paintings in “the hierarchy of bad, better, good, possibly great, despite the attempt of the artist to deny us the satisfaction of old-fashioned discrimination.”

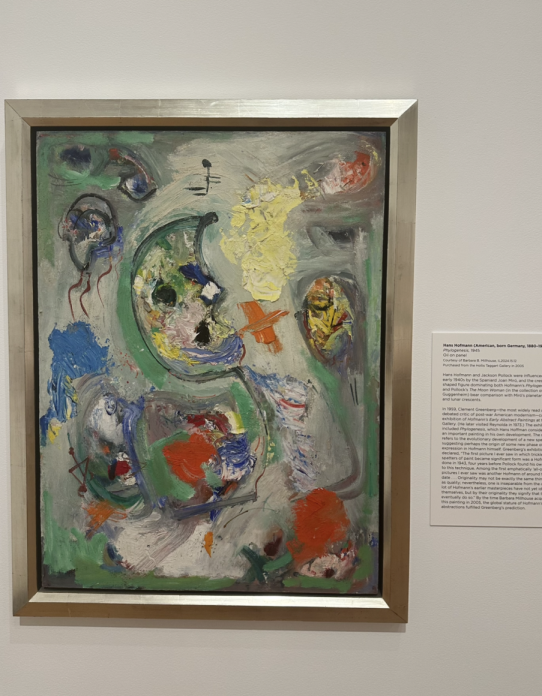

Looking at the exhibit as a whole, it is difficult to tell what Millhouse’s criteria are for such an assessment. The assortment is eclectic in the extreme across forms, textures, moods and subjects. Some paintings, like Hoffman’s “Phylogenesis,” gave me the immense pleasure of looking at an image that deserves (or demands) a new word of its own. Works like the untitled project employing “wood, paper collage, watercolor and graphite on panel” by Louise Nevelson left me out in the cold, confused. There seemed to be no clear continuation or through-line from one piece to the next, but rather a cacophony of voices vying for their own space in the world of modern art. Surprisingly, what emerged from the exhibition for me seemed to be not necessarily a reflection of one individual’s decisive taste, but a record of American artists’ struggle to break away from and supersede the artistic innovations they inherited from Europe.

The collection, which is free to view for those in the Wake Forest community, is something every student should go see. On the other side of a pleasant stroll along the Reynolda trail is a blend of old masterpieces and recent discoveries, with something for everyone to see.