Although Hurricane Helene did not send floodwaters directly to Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., the hurricane brought catastrophic flooding, landslides and widespread damage to western North Carolina counties. More than 1,400 landslides were reported in the mountainous region, damaging thousands of homes, roads and bridges; about 220,000 families sought federal assistance in the wake of the disaster, according to the National Public Radio (NPR) network, the public radio network of the United States.

“It is no exaggeration to describe Helene as the deadliest and most damaging storm ever to hit North Carolina,” Gov. Roy Cooper said, according to NPR.

As the planet warms, rising temperatures increase evaporation rates, and warmer air holds more moisture, leading to more intense rainfall events. In general, hurricanes, tropical storms and other weather systems are becoming stronger due to increased temperatures and moisture, according to Steve Smith, geologist and assistant teaching professor within the environment and sustainability studies program at Wake Forest.

In North Carolina, this is evident by heavier rainfall during storms, which exacerbates stormwater management challenges. Urban environments, including campus settings like Wake Forest, face similar issues, as large volumes of water from storms need to be managed effectively.

“One of the greatest risks that we face from climate change is flooding,” Krista Stump, manager for engaged and experiential learning at Wake Forest University’s Office of Sustainability, who has been actively focusing on stormwater management, said.

Stump defined stormwater as water that runs off impervious surfaces like roads and buildings when it rains, instead of being absorbed into the soil as it would in natural landscapes.

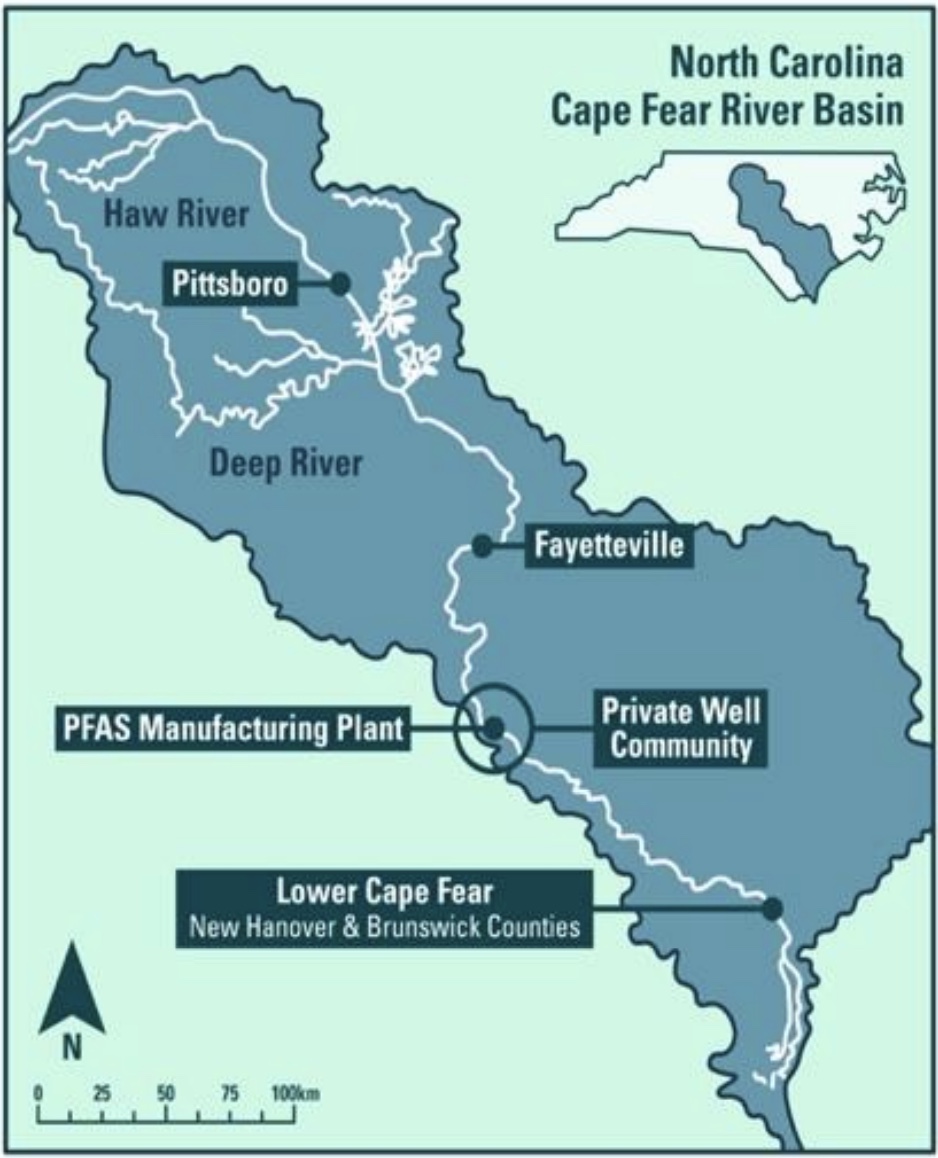

This runoff can pick up pollutants such as litter, fertilizers, pesticides and oil, which then flow into nearby watersheds, contributing to water pollution.

Stormwater management traditionally involves using pipes, ponds and drains to redirect water. To address this, low impact development (LID) tools are used to mimic natural water absorption processes. These include rain gardens, buffer strips, bioswales (planted ditches), cisterns and green roofs. These approaches help manage stormwater in a way that is more sustainable.

With her experience of working in Florida, where stormwater management issues are also prevalent, Stump has witnessed many ways that stormwater was handled. She appreciated Wake Forest’s stormwater management practices and design.

Tohi Garden, a “stormwater pond” behind Maya Angelou Hall, is an LID stormwater management site where water from campus flows in, allowing particles (like soil from erosion) to settle out as it moves. The pond is surrounded by a wild, forested area, where plants help with stormwater management.

Another LID site is situated on a hill behind Winston Hall. Wake Forest created the Winston Hall Rain Garden to address erosion and pollution from water running off the roof and parking lot. When rain washes away from the copper roof, it carries molecules of the metal roof that infiltrate the soil.

Since copper is a recognized biocide, a chemical substance or biological product designed to kill, inhibit the growth of or repel a specific organism, runoff contaminated by copper can kill plants over time. To counter this situation, the rain garden uses native, pollinator-friendly plants to absorb the runoff water and reduce erosion.

Stump emphasized the importance of protecting trees for stormwater management. Tree canopies slow down rainfall, and their roots absorb water. During construction, it is crucial to protect natural areas and design spaces to support stormwater management.

The campus also ensures there are trees planted next to the parking lots. Behind the Farrell Hall, there are large oak trees. To protect these trees, a bridge was built over them to provide a pathway to North Dining Hall, preserving the natural area while offering access.

Stump’s daily work involves helping faculty incorporate lessons about sustainability into students’ main courses and guiding campus tours to showcase sustainability efforts. Similarly, Smith and the Office of Sustainability focus on raising awareness about environmental challenges like stormwater management and flooding.

“We are at a place where our stormwater management infrastructure has been in place for 50 years,” Stump said, “and it wasn’t created to account for all the changes that we’re experiencing right now. As we’re going back [to] retrofitting stormwater management, we need to be future-focused and make sure that we’re building these systems in a way that can handle any increase in demand.”