The historical thread of humans trying to rid themselves of their humanness is long and fairly easy to track. 1950s suburbia (although there are innumerable earlier examples) comes to mind. That specific attempt at benumbment in postwar America epitomizes our endemic condition. The country, traumatized by the horrors in Europe, wished to return to a simpler, safer time. This “simpler” time was not the ur-human, hunter-gatherer time that Rousseau craved after his stint in egoistic France, but instead was comprised of the sterilized emotions of a shell-shocked nation. It was a time of marriage as a stable institution thought to be concomitant with stable happiness. Roles were defined by marketers and we blindly tried to assimilate their quixotic templates. Life was made simple in the wake of its endlessly-horrific complexity. That trend, marked by the impossible demands of a mediated society and that led the retreat from humanism, continues to prevail today.

The new Netflix documentary, Take Your Pills, is the 2018 equivalent of a John Updike story. It chronicles the bromide of 2018, but is just another permutation of the 1950s, postwar repression Updike keyed into. Although now we live in a society that is sexually and socially “freer” than the 1950s, that does not mean we are more emotionally attuned. We have become the bourgeois nightmare of the postwar capitalist boom.

Take Your Pills centers around this nightmare, charting the tsunamic wave of stimulants that floods our society. In the age of “capitalism as humanism,” Adderall, Ritalin, Vyvanse and all other low-grade meth-equivalents saturate both the legal and black market to satisfy the needs of our “go-go society,” as Owen Glieberman calls it.

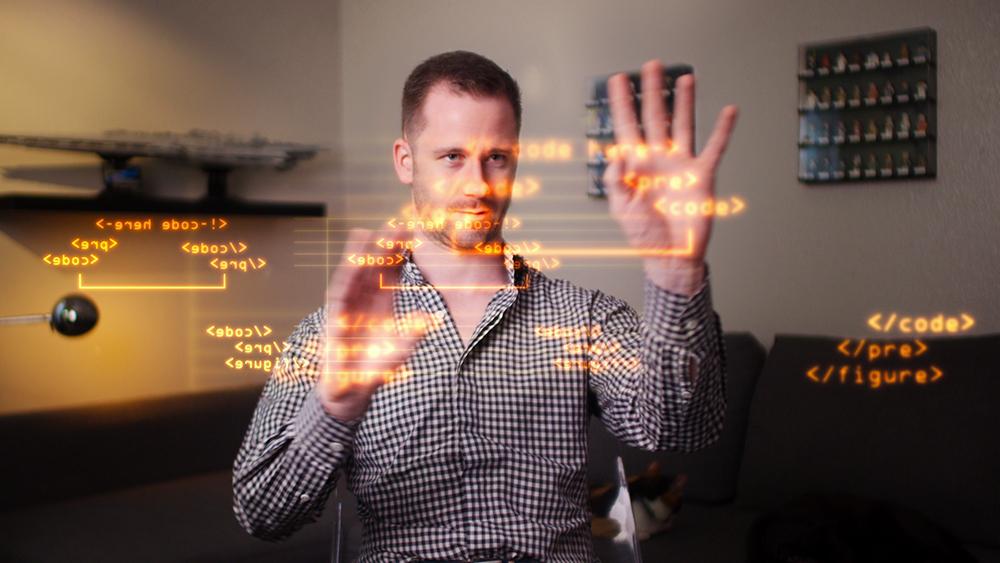

In the film, we are shown college students who take this “focus drug” to crank out papers, study for tests or unshoulder massive amounts of stress, all by inducing the fugue-ish state of concentration that drugs like Adderall provide. Wall Street analysts tell of how they work drug-fueled, sixteen-hour days to keep up with the ridiculous demands of the finance industry, and Silicon Valley coders expound the new, stimulant-driven paradigm that allows them to aspire to the type of code-spewing geniuses they are assumed to be.

The documentary dives into the history of the drugs themselves (there is a particularly interesting anecdote about how Ritalin came to get its name), and tracks their rise all the way from inception to diet pills to modern-day knee-bouncers. The long-term health effects of the drugs are presented too, but seem to drown in the capitalist fervor driving their consumption. Much of what we already knew and thought about how these low-grade amphetamines work is corroborated by experts, but that doesn’t mean they are becoming any less prevalent.

The ADD/ADHD myth is never succinctly answered in the film, precisely because both conditions have such slippery criteria for diagnosis. Those using and abusing the drugs, both through iffy prescriptions and not, make their way to the fore. Most powerfully, those who seem to actually “need,” the drugs chastise their long-term effects as crutch-forming and life-draining.

But perhaps the most interesting part of the documentary is not the nitty-gritty of the drugs themselves, on which much is expounded through creative graphic-design, but rather the more meta questions the film poses to its audience, most of whom have probably had first — if not secondhand experience with the go-go drugs that pervade our lives.

Take Your Pills turns into a meditative cultural exposé and launches the ostensibly myopic topic into a larger cultural sphere. It asks what the mass consumption of these drugs says about our culture at large and calls into question American capitalist existence, with its insanity-inducing stress of product and capital.

No normal mind can deal effectively with the nebulous, yet emotionally devastating, demands of the international capitalist market. Our human capabilities in the face of what we view as profoundly impactful incidences are not up to the task. Drugs like Adderall induce a frenetic focus that makes us think we have a handle on our capitally-determined lives. The pill we take to get a better grade, to be able to code for sixteen instead of fourteen hours, is taken because it is perceived to generate an incremental increase in our production value. That we see ourselves as mere capital products is the crux of the issue. Everything revolves around our chance of ascending the hyper-competitive ladder of the professional world. Unfortunately, this results in a decrease in our human valuation, and does not necessarily lead to any genuine happiness.

Society puts us in a mode of constant capital relativity, and the pills are a chemical attempt to assuage the breakneck dread of our condition. They are an escape from humanness into the synthetic realm of capitalist distraction. Existence becomes a competition of accoutrements. In a society based on acquisitiveness, what we strive for is not so much human connection and interpersonal value, but the accrual of our own capital value. We monetize ourselves and our skill-sets, and the capitalist treadmill leads the not-stimulated mind to a sense of perpetual inadequacy. Luckily (and, yes, I feel I must point out that this is sarcasm), there is Adderall.

The most basic question, yet I think also the most important, is what the documentary implicates the psychotropic drugs with: a culture paralyzed by capitalist cravings. Consumption of Adderall as a PED is symptomatic of the “empty calorie” approach to life, where everything is viewed as product, capital and managed assets. To further oneself, one must properly alienate themselves from their humanity, which naturally allows for impulsive connection, wandering thought and emotional failure. Those are unnecessary evils to our profit-driven bottom lines, but crucial in the business of being a human being. “What is this all for?” Dr. Wendy Brown, a political theorist at UC Berkeley, asks. As she attempts to conjure up an example, she tells her interviewer: “I just lost my thought, hang on one second,” — yet another meta-example of the natural rhythms of the mind. She finally goes on to say, “What we also might say is lost [through these drugs] is what human beings do when they muse, when they reflect, and when their thoughts wander … And out of that comes what? Creativity, art, extraordinary moments of human connection. Of course, also moments of intense human pain and grief. But I would describe them as the experience of being human itself.”

It’s a shame, really, what we do to ourselves through the act of fleeing. We try to make our lives “tolerable” by turning our heads away from ourselves. When are we going to learn the only satisfactory answer, which is, of course, not an answer at all, but is the pulsation of us? “What is the cost of material progress and productivity, and is that a cost we’re willing to live with?” Anjun Chatterjee, professor of neurology, asks. It’s more than just a question worth reading.