Moondog, the besotted writer-radical at the center of The Beach Bum, is the spiritual sibling of many men before him. Played with a sort of inevitable alacrity by Matthew McConaughey, Moondog’s hedonistic bliss borrows from Mickey Rourke’s pathetic and disturbed Henry Chinaski from Barfly, the mythos of Hunter S. Thompson and perhaps most heavily from Jeff Bridges bumbling burnout, The Dude, from The Big Lebowski — except Moondog subtracts the pitiable profundity of Rourke, the schizophrenic productivity of Thompson and supplants The Dude’s postwar chill with a larger social allergy. McConaughey’s amalgam exemplifies, above everything, the cosmic mirth of a bottom-feeder genius, forgoing most all seriousness in favor of bohemian excess.

Written and directed by Harmony Korine, The Beach Bum satirizes our desire to blend chemical with existential addiction. The Beach Bum, though, hardly ever bleeds into the paranoiac world of a film like Trainspotting, where slapstick eventually curdles into an eerie fatalism. Instead, the film prefers to ground itself in a sort of Belfortian excess achievable by all, mixing personal abdication with spiritual liberation, forming a positive film with a only a light layer of satire.

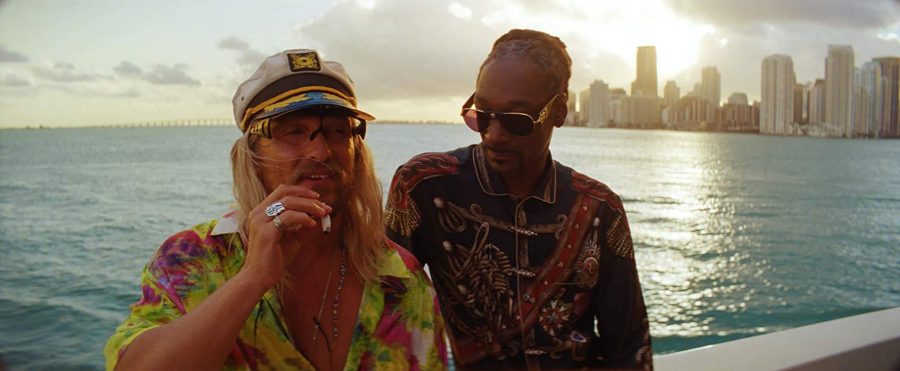

The film follows Moondog, a poorman’s Hemingway, living in Key West, subsisting on drugs and women and maintaining local celebrity status as the writer who’s tired of civilization. Lewis, Moondog’s agent, played with Southern flamboyance by Jonah Hill, implores Moondog to reach into his dormant genius and write them both a check. Soon though, after more than a few minutes of deflecting and imbibing, Moondog is drawn out of his sun-soaked bender by his wife Minnie (Isla Fisher), an extremely wealthy woman living in Miami with her gangster paramour, Lingerie (Snoop Dogg). Moondog motors his tiny skipper from the Keys into high-society as his daughter Heather’s (Stefania LeVie Owen) wedding day approaches. Upon arrival, despite the blatant infidelity, Moondog and Minnie fling themselves into sexual union, showing their mutually exploitative relationship to be germane to both parties. Heather’s husband-to-be should have heeded the warning from Snoop Dogg that “this family is f*cked up.” He should know.

The Beach Bum starts (and continues) with montage after montage of Moondog’s slurring serenity as he gets blitzed, tells Lingerie about the time he plagiarized D.H. Lawrence and then flashes into a melic frenzy with the homeless. After a passionate, post-wedding jaunt, deeply saturated and framed by Korine to show the two’s gush of substance-fueled symbiosis, Minnie dies, and Moondog mourns her death as both a human and financial disaster. In order to claim his half of the fortune, Moondog must publish his once-anticipated (now by most considered belly-up) book of poetry. This is supposed to be the fulcrum of the adventure-to-come, as if the build hadn’t been a thorough-enough soaking, and the rest of film involves bit players like Flicker, Moondog’s rehab escape-partner, played by Zac Efron, who, in attempting scuzziness still came out overly-buffed, and Captain Wack, an aiding-and-abetting ship-head played by with maximum voltage by Martin Lawrence.

Like Spring Breakers, Korine’s 2012 feature satirizing an American value system that warrants our annual orgy down-south, The Beach Bum seems to have some sort of cultural target in mind, but its more occult nature (the intelligentsia and their fetishization of the tortured writer) leaves Korine to lavish in style and excess to the point of superficiality. Spring Breakers, with its “Girls Gone Wild” ethos, exposed a paradigm and hyperbolized the sex, drugs and violence endemic to our escapism. Through super-saturated, impressionistic scenes, Korine gave us slashes of experience that mimicked the lurid content itself. By placing us in a sleaze-o-sphere of stylized madness, Korine created a singular film that isolated the tragically entertaining, endlessly provocative energy behind one of American college students’ oldest traditions. One does not soon forget the looney brilliance behind James Franco’s impassioned cover of Britney Spear’s “Everytime” because of the incisive totality of the film itself. The excess, in a way, proved salvific. But The Beach Bum portrays a sort of flattened madness, as if Korine himself didn’t have much artistic energy left, eeking out a pandering parody, wallowing in the shallows and capitalizing on big-name actors who rightly enjoy the chance to be demonstrable. The cultural critique central to The Beach Bum seems to come from an exhausted film-maker, one whose fading vision takes aim at a barely salient subject, and an over-wrought one at that.

Sort of like Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, where audiences walked away from a cautionary tale whooping for Belfort, appropriating his ethos instead of absorbing the metaphor, few people will come away from The Beach Bum realizing what Korine is doing. Instead, they will see Moondog and his lifestyle of profligate pleasure as one to be, if not mimicked, at least to be laughed at. Thus is the problem with satirizing lazy writers; they can infect the camera, especially with an actor as talented as McConaughey. It’s no fault of the actor’s if the film itself becomes a voyeuristic trip, entranced so deeply by its subject that its art becomes artifice.

The Beach Bum ends up with little moral texture, grinning at audiences as McConaughey stumbles into drink, orifice and even occasional profundity. It becomes a pointless parody without legs, skating on the actor’s ability and film’s inherent entertainment value. Unlike Spring Breakers, whose excess and absurdism evoked warranted critical excitement, The Beach Bum relishes in its excess to the point of critical abandonment. It represents its brand of cinema as a desensitizing experience devoid of potential message or potency. While good satire floats just above inundation, or weathers the deluge with a kind of eloquent absurdism, The Beach Bum, with its boilerplate blowouts and throwaway theories, never even gets off the ground.