The gap between our contemporary conception of the Holocaust and that of its historical reality is often bridged by a series of grave images or narrative confessions. Both aim to impress the tragedy on our consciousness, but their directness — a frank admission of scale and depth — abstracts the event out of feeling and into fruitless logic. Our brains try to reason with the unreasonable, though it is nearly impossible to not only comprehend but then to understand the Holocaust’s countless victims. The word “Holocaust” has been emptied, voided of meaning because it now feels banal, a mix between a stand-in and a catch-all for the ungraspable, proving that empathy can only really bloom through tiny, individual intimacies. Though perhaps initial, honest accounts of the Holocaust helped us achieve a kind of clarity, by now, those images are mostly inert to contemporary audiences. We have been saturated with (moving) pictures so alien to our brain that they exceed its capabilities. The further removed we are from the colossal cruelties that took place, the more our reactions become prosaic and insincere, increasingly stymied by historical distance.

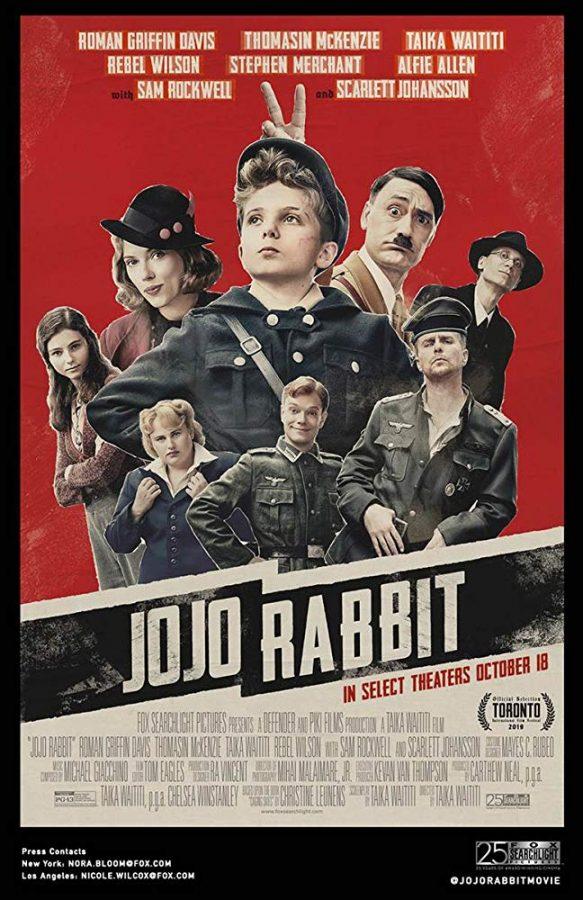

Jojo Rabbit, written and directed by Taika Waititi (The Hunt for Wilderpeople, Thor: Ragnarok) re-imagines history through the eyes of a fanatical 10-year-old German boy named Jojo (Roman Griffin Davis), whose affinity for Nazism comes across as the type of obsession belonging to Star Wars or Harry Potter. Donning the party uniform and mindlessly reciting creed, Jojo, in his sincerity and obvious sweetness, epitomizes the desire of all young children for a clear, comprehensive universe. In this case, that universe is defined by the ethics of fascism, but the viewer suspects the Führer’s broad-strokes philosophy may be inadequate for a sensitive 10-year-old and needs only a convincing foil to crumble. Waititi himself represents Hitler as a diffuse illusion, pecking at Jojo’s mind with his goofy, empowering presence. For a young boy with few friends, Jojo’s imaginary Hitler becomes a source of patriarchal encouragement.

The film begins as Jojo attends a kind of benighted, Boy-Scouts-for-Hitler boot camp, where a troop of 10-year-olds are to be trained as soldiers (Germany is on the verge of losing the war and is galvanizing all its resources). The children cheer at the prospect of murdering Jews, and the mood is one of bumbling and desperate inculcation. Trained by Captain Klizendorf (Sam Rockwell), a barely interested homunculus who knows the end is near, and Fraulein Rahm (Rebel Wilson, caricaturing the hyper-dogmatic type), the Hitler Youth act more like badly crowd-sourced sweethearts than nascent killers. Yelps of mindless conscription pierce the air, taking the historical reality and divesting it of momentous evil. Instructors become the weary flag-bearers toeing the party line, inducting the young men into a tired club. The Nazi emblem burns above Rockwell’s shrimpy noggin as he is introduced in close-up, his symbolic strength belying an intrinsic puniness and, by now, his (and the regime’s) apparent failures. He never feels like a threat, more like a negligent nag, and Rockwell plays him with the faux-moxie required of a man whose cracked, stick-to-your-guns ethos is required all the way to execution.

When Jojo is unable to twist a rabbit’s neck, he’s nicknamed “Jojo Rabbit” for his weakness. But after a pep-talk from his imaginary Führer, he returns to prove his worth by charging through the crowd and hurling a grenade that bounces off a tree and blows up, barring him from the front and scarring his face in the process. In the hospital, we meet Jojo’s mother, Rosie (Scarlett Johansson), a musical, strong-willed and thoughtful amalgam of everything the Nazis were not. She aches for the war’s end, which will hopefully allay Jojo’s insidious obsession, and though she shapeshifts from ebullience to melancholia to some introspective in-between, her fraught psyche is manifest. Johansson is stellar, precisely because her light is anathema to the simple darkness of others, a complex interjection of voices that collect in flashes of authenticity. She knows her son, almost unabashedly better than he knows himself.

As Jojo convalesces, he discovers Elsa (Thomasin McKensie, dew-eyed and crackling with suppressed intelligence), a Jewish girl living in his sister’s bedroom wall. Slowly, Jojo’s 10-year-old devotions are blinded by love as Elsa ruffles his pretenses with her penetrating intelligence and poetic sensibility. The two actors orbit each other wonderfully, trading jabs until they crash into compassion. Griffin Davis has features that bubble up in twitches of self-discovery, and McKensie, who first won my silent sympathies in Leave No Trace, plays Elsa with a soft, observant honesty.

The kind of de-mything in Jojo Rabbit has been done before, in various ways, that revealed historical figures as running institutions of controlled chaos, not streamlined efficiency. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino’s renegade violence undermined the Nazis through historical invention and injected occupied France with a violent, comedic rebel spirit. There is humor in Jojo Rabbit, too, but the entire film feels more confectionary than anything Tarantino has made, like the kind of less involved Wes Anderson we saw in Bottle Rocket, before style became sole substance. Yet Jojo Rabbit is never saccharine nor one-dimensional; instead, its sincerity clings to the emotional moments and accentuates its few gut-wrenching twists. Because the impenetrable gravity of history warranted a new sensibility, Waititi’s unique project resists feeling like a trivializing gloss. The film presents Nazism as another example of gaslighting, using circumstance as a vehicle for effective storytelling. It isn’t reductive, because the history has been over-lit and reiterated to the point of anesthesia. By quoting Will Hunting, Jojo Rabbit makes Nazism about as arbitrary as eating caramels and allows it to merely ornament a denser bildungsroman in a fresh and relatable way.

Jojo’s mother likes to dance, and often implores her hard-lined son to participate, as if it would release him from his premature cynicism. Elsa, too, claims the first thing she will do upon liberation is dance. Jojo’s youth has been co-opted by “adult” ideas of belonging, a ludic drive guided toward a narrow mania. Jojo Rabbit, though concerned with the perspective of a boy invaded by Fascist precepts, is broadly about the things we teach our children, at all echoes of relation. The historical analogue is extreme only because it takes an inscrutable regime and clarifies its parts, condensing a central human conundrum into a small boy’s squishy ideas of life. The film is a miraculous feat, if one really thinks about it, to allow us to empathize with a historical atrocity, yet simultaneously extend its questions into contemporaneity.

The reality of social existence requires a degree of corrupted innocence, but the film seems to indicate that a total loss of imagination is what fertilizes philosophies of cynicism and isolation. The human instinct that feels through play must be granted light. To recognize life as a flux of the unknowable mixed with occasional human clarity is to give up some control, to believe the uncertain lives alongside philosophy. The strongest thing in the world, Rosie tells Jojo, is love, and it exists in a space of play. To quote Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio / than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Those things, Jojo Rabbit tell us, consist of spiritual melody, entangled emotion and the mind consciously falling into another’s universe.

婚书网 • Dec 4, 2019 at 2:04 am

已加入收藏夹,时不时的来看看有没有更新博文!