Student athletes lack compensation

October 8, 2020

In October of 2014, the Georgia Bulldogs football team was rolling towards a 10-3 season when running back Todd Gurley III was suddenly shackled by the NCAA for the illegal sale of some unspecified goods.

The profit turned out to be $400, and the goods –– his jerseys with his name on them, according to Business Insider.

With “Gurley III” already on the back of tons of apparel that had the number three on them, his staggering 42 career touchdowns, and his projection as a first-round pick (that came true), he was bringing in tons of revenue for both the University of Georgia and the NCAA, according to sports-reference.com. Even so, his accumulation of $400 was $400 too much for either organization to tolerate.

This is just one of the many examples of how the NCAA has been stealing the likenesses of athletes for years.

It’s true, Gurley was just another face in the crowd of marginalized athletes that included fellow Southeastern Conference football players Johnny Manziel and A.J. Green. Like sweatshops in China, the NCAA is running a very specific sort of business here and it’s one of exploitation and commodity.

“This is the more tangible effects of the economic side of sports,” said former offensive tackle for Penn State Chima Okoli who is now an attorney.

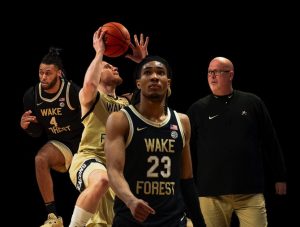

The overarching problem is the NCAA’s classification of college athletes. Division one athletes (particularly football and men’s basketball players) bring in scores of revenues for their universities by helping them garner TV and apparel sponsorships which effectively makes the NCAA rich in the process. However, this organization still refuses to pay these athletes or really let them accumulate any capital at all. They place these actions under the claim that college athletes are amateurs not professionals.

“You can not call them employees but call them ‘amateur’ and cut them off from all funding,” Okoli said. However, these amateurs are still featured in commercials, advertisements, 40-foot billboards and even video games … yes, video games.

“There’s a huge point of contention between the NCAA and Entertainment Arts who made the game,” Okoli said. “It’s a gray area.” EA and the NCAA conveniently fill that gray area with substituting out names, for position and number: Example, Todd Gurley is renamed, “HB #3”.

Money talks and big corporations like the NCAA and its flagship universities — they listen.”

But why does the NCAA go to such extreme lengths to exploit these players? Well, in simple economics: as the cost of labor increases, so does the cost of production. At a certain point this combined cost surpasses profit. However, if someone can figure out how to eliminate the cost of labor, production costs will also be zero and profit will then soar. This means that somewhere in the NCAA there’s probably a really smart and groundbreaking microeconomist!

Or there’s possibly just a widespread lack of value for workers’ rights. Yeah, we’ll go with that one.

So athletes work like employees yes, but aren’t they paid enough with scholarships and the potential to play professionally? The best answer to this question is, put most eloquently as, “no.”

Here’s the reality: out of every student athlete, 6.7% of them are on scholarship, per scholarshipowl.com and not even two percent of them will ever see the pros according to theconversation.com. That’s a lot of unpaid labor left out there.

“It’s a position where you pretty much fill the role as an employee,” Okoli said.

Luckily, in 2021, reform is coming as the NCAA will allow athletes to slowly be able to reclaim their namesakes. However, it is doubtful that this system will ever fully change. Money talks and big corporations like the NCAA and its flagship universities –– they listen.

“Once athletic directors realize that huge sums of money come from our amateur program … it’s hard to change that system,” Okoli said.