New vaccines are over 300 years in the making

Centuries of science have led to the creation of the three FDA- approved COVID-19 vaccines

March 11, 2021

It has been over a year since COVID-19 changed the way the world functions. During the course of these past 12-plus months, the scientific community has pushed the boundaries of what we know about infectious diseases and how to treat them. Several vaccines have already been developed, approved and put into circulation to combat COVID-19, a remarkable feat considering the novelty of the virus.

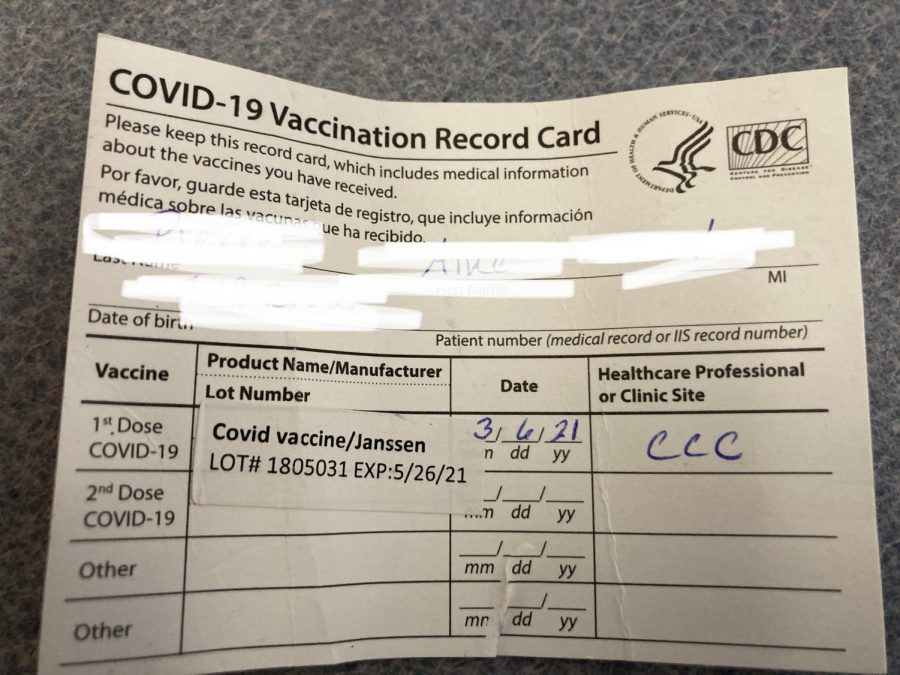

The new Johnson & Johnson vaccine, approved last week for emergency use by the FDA, may seem like it was only one year in the making. In reality, it and its companion mRNA vaccines — the brainchildren of Pfizer and Moderna — are the result of three centuries of work.

Vaccines first emerged in the late 1700s when Edward Jenner developed the first successful vaccine to treat smallpox. Since then, many other vaccines have been developed to treat infections ranging from polio to measles to the influenza virus. Techniques for vaccine production have also evolved throughout the years. The first vaccines inoculated people using similar, but less severe versions of the virus. Today’s methods have begun to experiment with incorporating the genetic code of the virus — such as DNA or RNA — in the vaccine to create more effective protection.

Vaccines typically work by exposing the body’s immune system to a pathogen. This method allows the immune system to produce the antibodies that will grant the body immunity if it comes into contact with the actual virus. The pathogens in a vaccine are typically weakened or killed. Vaccines, therefore, are an especially effective type of treatment because they prevent a disease rather than treating it, thereby curbing the spread before it affects too much of a population.

Two specific types of vaccines have become especially relevant thanks to COVID-19: mRNA and viral vector vaccines. Both types of vaccines utilize a portion of genetic code from the disease that they are meant to prevent.

mRNA vaccines, such as those developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, are a fairly new type of vaccine. They use a piece of mRNA to instruct the body’s cells to make a spike protein, which is a portion of the virus found on the pathogen’s surface. By itself, a spike protein is harmless. But when the body produces these proteins the immune system recognizes them as foreign, and an immune response is triggered. This immune response involves the formation of antibodies, which grants the body a higher level of immunity from COVID-19 if it ever encounters the actual disease. However, the difficulty with these vaccines is that they require two doses, spread weeks apart in order to gain a high enough level of efficacy.

In contrast, viral vector vaccines, such as the one Johnson & Johnson developed, use an adenovirus as a vector to introduce the needed gene to the body’s cells. Like mRNA, the vector carries the genetic code for the COVID-19 spike protein, allowing the body to produce an antibody response to COVID-19 without actually being infected. The adenovirus used as the vector is engineered to be entirely harmless and only delivers the needed gene without harming the recipient of the vaccine. These types of vaccines are especially convenient because they only require a single shot.

All of these vaccines are entirely harmless and, according to the CDC, may only cause short-term side effects including pain, redness, or swelling at the injection site and tiredness, nausea, fever, chills, muscle pain and headaches throughout the body. Furthermore, despite the use of genetic code in the vaccines, neither the mRNA vaccine nor the viral vector vaccine induces any alteration to the DNA of human cells. Vaccines are invaluable in helping stop the spread of disease and keeping the population safe.

According to the New York Times, President Biden is “directing the federal government to secure an additional 100 million doses of Johnson & Johnson’s Covid-19 single-shot vaccine,” which may allow children to be vaccinated and additional booster shots to be administered in order to better address new strains of the virus. With any hope, the vast majority of the U.S. population will be vaccinated by some point this summer.