Winston-Salem schools begin reopening

Under a new state law, elementary, middle and high schools start the slow process of resuming in-person classes

R.J. Reynolds High School, in the same district as Mt. Tabor High School, is three miles from Wake Forest’s campus.

March 11, 2021

Though Wake Forest University has been offering in-person learning opportunities to students throughout the 2020-21 academic year, other Winston-Salem-based students have not been so lucky — but this is about to change thanks to the leadership of Governor Cooper and Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Superintendent Tricia McManus.

As highlighted in Gov. Cooper’s school reopening plan that was published over the summer, there are three phases within the North Carolina school reopening strategy: Plans A, B and C.

Plan A states that all students are allowed to attend school at the same time, though teachers and older students must wear masks. Plan B limits school capacity to 50% and calls for students to alternate between engaging in in-person and at-home learning. Plan C calls for fully remote learning with no opportunity for students or teachers to work within the school building.

When COVID-19 cases soared across the state in July, Cooper only allowed schools to open using Plan B and Plan C guidelines.

Now, change is on the horizon.

On Wednesday, March 10, Governor Cooper and a bipartisan team of North Carolina Senate leaders announced a plan that would push all public elementary schools to reopen.

According to the legislation Cooper and the North Carolina legislature released, all elementary schools must operate under Plan A.

This bill will take effect 21 days after Cooper’s signature hits the page, and the changes it discusses are expected to be instituted sometime around April 1.

The legislation that Cooper and his team released on Wednesday stated that individual districts will make the decision of whether or not middle and high schools will operate under Plan A or Plan B.

In a press release posted directly on the Winston Salem/Forsyth County Schools website, it was announced that per the recommendation of Superintendent Tricia McManus, a number of WS/FCS high schools currently using a four-cohort model will transition to a two-cohort model beginning Monday, April 12.

But the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County school district serves a far larger population than a handful of high schools.

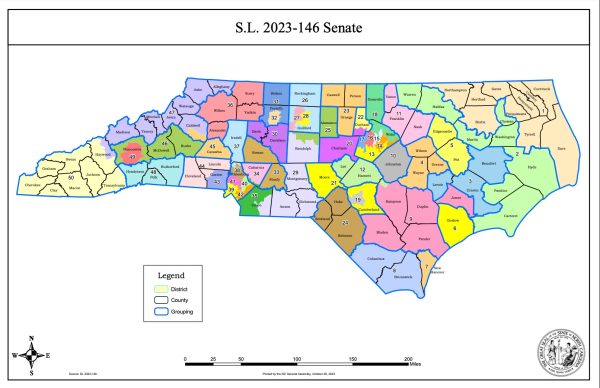

The Winston-Salem/Forsyth County district is home to 80 magnet, non-traditional, elementary, middle and high schools. The school district serves approximately 55,000 students and employs over 7,200 people. According to the WSFCS website, the district is the fourth-largest in North Carolina.

So, while the majority of high schools and elementary schools are slowly preparing to transition back to in-person instruction, some middle schools are being left behind in the process.

Jefferson Middle School, Meadowlark Middle School and Southeast Middle school are three schools within the district that will continue operating as four cohort programs.

Jefferson Middle School is only an eight-minute drive from Wake’s campus. However, the in-person attention that students receive at Jefferson is nowhere near comparable to the treatment that university students receive.

Jefferson houses over 1,200 sixth, seventh and eighth-graders. Due to the number of students the school serves, the school cannot currently offer in-person instruction to students more than twice a week, every other week.

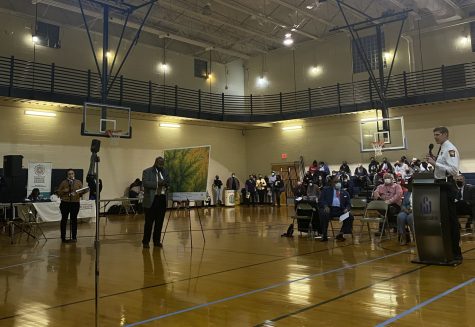

Taylor Hamby teaches sixth-grade social studies and language arts at Jefferson Middle. When asked about the blended curriculum that Jefferson is currently employing, she considered the changes in teaching methods that the school has endured since COVID-19 shut down in-person instruction throughout the state last March.

“Not only did we [start remote last March], we were mostly asynchronous,” Hamby said. “So, there weren’t Zoom meetings or a regimented schedule. It was just us posting lessons and work on our learning platform, and then it got completed at [the students’] own pace.”

Hamby explained that, while she is grateful to be back in person and see each of her students a few times a month, this past year has been emotionally draining for her and her co-workers.

“Today, for instance, I only had six kids in my first-period class,” Hamby said when asked what one of her typical days teaching looks like. “So, I would have those six in person and then 24 students calling in through Zoom. And that is such a challenge. Just trying to answer questions in person and on Zoom and keep kids engaged and all. It’s a lot.”

Eleasa Allen is the parent of a Jefferson Middle student and understands firsthand the impact that the extended period of online schooling had on students and families.

“My daughter is going to school two days every few weeks,” Allen said. “I guess that’s better than nothing. But in my mind, that’s not ideal.”

“I candidly thought about just opting for online instruction, which was an option,” she continued. “But [my daughter] asked me to go back to school. She needed it for the mental and social aspects. And I want her to have that.”

But navigating the first few months of completely online schooling proved difficult not only for Allen’s daughter, but for students around the district and state.

According to test results shared with the North Carolina State Board of Education, the majority of high school students across the state did not pass state-mandated end-of-course exams administered in the fall. Additionally, some North Carolina school districts are reporting that 23% of their students are facing potential academic failure and will not advance grade levels at the end of the year.

The issues of inequity and school crowding perpetuate these difficulties.

“COVID-19 and remote teaching illuminated so many issues of equity not only in the county, but even within our school,” Hamby said. “We’ve got kids who don’t have Chromebooks, they don’t have internet access at home. But our school — God, I love it — we’re addressing the issue the best we can. We have such a variety of experiences shown in our school and, like I said, these gaps are definitely illuminated and some change will hopefully come out of it.”

Hamby believes that teachers, administrators, students and parents alike understand the implications that this unprecedented year of learning has had on the future of education.

“My feelings about how the last year or so have gone are not a reflection of my dissatisfaction with the school system or of any of the teachers or administrators who are running the schools,” Allen said. “But I think for me, it also 100% solidifies that schools are overcrowded. You know, the fact my daughter’s school is so large that they can’t maintain physical [social] distancing to allow them back to school says something. I think it is very telling for where we put our priorities going forward.”

Despite the issues of virtual learning and the slow process, teachers and parents are grateful for the work that politicians, school administrators and educators have done to ensure the eventual safe return of their kids to the classroom.

“I am in awe of the children — my kids in the classroom — who have been so resilient and are learning so many skills that they would have never had to learn,” Hamby said. “And that’s both a positive and a negative. There’s always going to be two sides of that coin. But it has pushed all of us to be better teachers.”