Panel discusses housing discrimination

The seminar touched on issues of racial discrimination in housing prevalent in Forsyth County

September 23, 2021

A virtual panel on Sept. 16 hosted by Wake Forest’s Race, Inequality and Policy Initiative brought together professors from Wake Forest and other universities to call attention to the impact of evictions on communities of color, especially within Winston-Salem.

The 90-minute session was moderated by Wake Forest Anthropology Professor Dr. Sherri Lawson-Clark. The event also featured Wake Forest Sociology Professor Dr. Brittany Battle, Winston-Salem State University Sociology Professor Dr. Dan Rose and University of Massachusetts Amherst African American Studies Professor Dr. Toussaint Losier.

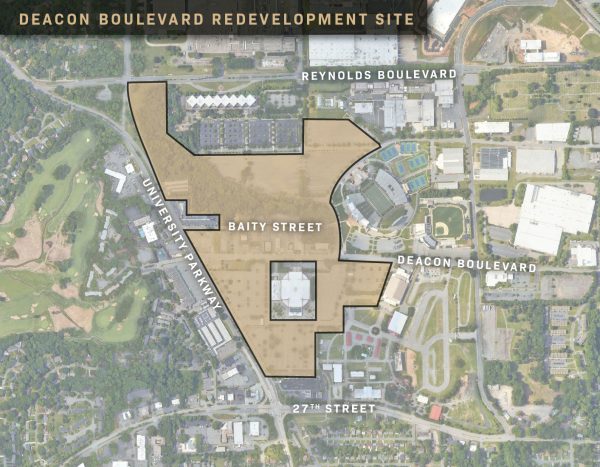

According to the panelists, despite Winston-Salem’s blossoming downtown renovations and reputation as a beautiful area to live in, decades of economic inequity have contributed to a pervasive issue regarding affordable housing in Forsyth county. In fact, studies have shown that the county has one of the highest rates of concentrated poverty — and one of the lowest rates of economic mobility — for low-income residents in the U..S.

“The high housing loss rates align with areas historically associated with segregation and redlining (an infamous technique used to exclude Black people from certain neighborhoods) as well as high concentrations of poverty,” Lawson-Clark said.

Battle began her presentation with an overview of the housing situation in Forsyth County prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. She demonstrated how even before COVID’s effect on employment emerged, many renters were struggling to afford their rent. Nearly three-quarters of residents were directing more than 50 % of their income toward housing costs compared to the “rule of thumb” standard of 30 %. Battle also said Winston-Salem had the 16th highest eviction rate in the nation.

Battle’s presentation went on to show how the pandemic exacerbated these long-standing issues. In spring 2020, rental assistance and shelter record requests increased by 75 %, with more than 31,000 people requesting those supports.

“Forsyth County is notorious for doing a really terrible job at providing affordable housing for our community,” Battle said.

Notably, the effects of housing loss were not equally distributed — rather, they were disproportionately tied to race. One study presented by Lawson-Clark showed that the relationship between race and housing loss was stronger in Forsyth County than in any other county included in the study.

“If we’re talking about evictions, we are talking about a racial injustice,” Rose said. “Housing justice, we like to say, is a racial justice issue.”

Along with his work studying housing loss from an academic perspective, Rose works with Wake Forest’s pro bono law clinic, the Legal Aid Society of North Carolina and Housing Justice Now — a grassroots organization in Forsyth County — to help connect vulnerable tenants with legal resources which can aid them in avoiding eviction.

Through his work, Rose connected with Shanty Lancaster, a local resident of Winston-Salem who attended the seminar and shared with the audience her experience of facing eviction after becoming underemployed.

The process was stressful, the working mother of three explained, and the conditions in the apartment where they resided were poor to begin with — mold and plumbing issues went consistently unaddressed by landlords.

“They do more fixing on the outside instead of fixing on the inside,” Lancaster said. “It’s not a healthy situation for my children, either.”

According to the presenters, steps toward creating more equitable housing policies include holding politicians — both local and national — accountable for the effects of their policies on low-income and marginalized communities.

At a local level, Rose mentioned Gloria Whisenhunt, the Republican county commissioner for District B, and former Clerk of Courts Juanita Tompkins, as perpetrators of dozens of evictions within the county.

However, as the national moratorium on evictions has been ineffective in slowing eviction rates over the past 18 months, Rose suggests that politicians may not be equipped to fully deal with this issue. Both he and Losier — who reported on the historical success of resident activism in beating back eviction efforts by downtown corporations and city officials in Chicago — suggested that social change must also be an integral part of proposed solutions to housing inequity.

“It is through mass movement that we have seen the most protection during this [eviction] moratorium,” Rose said. “And it will need to continue, especially now that the moratorium is over.”