Garden volunteers reveal inequity in Winston

Volunteers tend to gravitate toward more beautiful gardens in affluent communities

Volunteers, like those who come to help out at Campus Gardens, can put a dent in food insecurity in Winston-Salem, but certain gardens have greater impact than others.

November 18, 2021

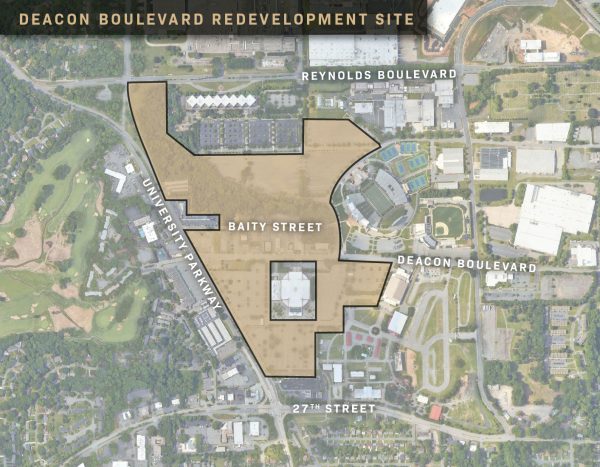

Wake Forest University is less than four miles from East Winston, one of the most food-insecure regions of Winston-Salem. Even still, only a handful of Wake Forest students volunteer at community gardens within the neighborhood.

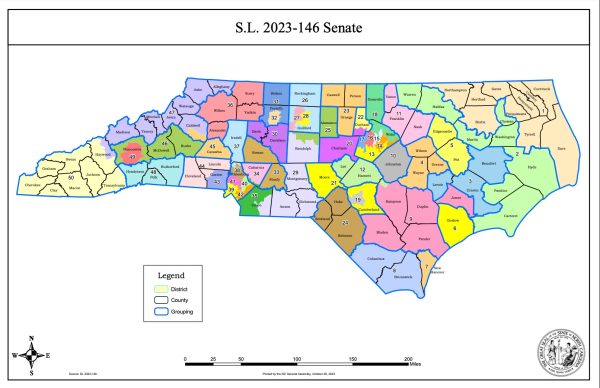

Food deserts are generally defined as geographic areas in which fresh, nutritious foods are unavailable for retail purchase. One in seven North Carolinians is food insecure. To address the widespread lack of accessible and affordable produce in densely populated areas, community gardens have proliferated in many urban areas across America. Winston-Salem is currently home to over 21 food deserts, despite the 90 community gardens also within city confines.

Most Wake Forest students who are interested in volunteering will choose to work at the WFU campus garden, or off-campus gardens like Crossnore Miracle Grounds Network, Gateway Nature Reserve, and Goler Community Garden. These are mainly situated in affluent parts of Winston-Salem. The gardens in East Winston get much less attention.

“When people volunteer, they want to give their time but also get something out of it,” community gardening program coordinator at Forsyth County’s N.C. Cooperative Extension Center Cameron Waters, said. “As a result, volunteers are going to want to go to beautiful, aesthetic garden spaces over the less pretty ones. But, those are the gardens that really need the help.”

Organized by Waters and Nathan Peifer — who manages Wake Forest’s campus gardens — a small group of students volunteer weekly at select gardens in East Winston, including the Diggs-Latham Elementary School Garden, West Salem Community Garden and the Neighborhood Hands Community Garden.

However, the group of two or three students showing up to these gardens pales in comparison to the 10 students who regularly attend Gateway Nature Reserve’s community work days.

“I’ve really enjoyed getting out of the Wake Forest bubble and gardening in the city,” senior Matthew Scoggins, who volunteers with Peifer at a garden in East Winston, said. “I think that we need to focus our efforts more on working with the Winston-Salem community on projects, rather than occasionally making donations.

“I like how the teams have formed close working relationships with our neighborhood partners,” Peifer added. “I’ll continue to nurture that aspect of the program, making sure we’ve got a skilled team of volunteers who can help achieve the community garden’s goals.”

Waters said that, as a Wake Forest graduate, she is appalled by the lack of knowledge within the student body in regards to gardens in East Winston.

“Wake Forest is right next to the most food-insecure parts of Winston-Salem, and even still, most people either don’t know about them or would rather go to a nicer garden, like the one on campus or at Crossnore, ” Waters said.

Most of the produce grown in the campus garden and at gardens like Crossnore is donated to non-profit organizations like Project Help Our People Eat (H.O.P.E.) and the Second Harvest Food Bank. Both organizations distribute the food and produce, including green beans, tomatoes, potatoes, and shelf-stable items, to families in Winston-Salem who are deemed food insecure.

“It’s hard for folks in less affluent areas to volunteer at community gardens, put the work in to grow their own food, and still tend to their other responsibilities like jobs and kids,” Waters said. “It really takes a village to keep these gardens going, and most people just don’t have the time to do so.”

Sophomore Tyria Zanders is the Campus Garden Intern at Wake Forest’s Office of Sustainability. Zanders said the divide between Wake Forest students caring about the environment and food justice and actually getting their hands dirty is a problem the Office of Sustainability is always working to solve.

“People at Wake Forest are either really passionate about gardening and sustainability and are willing to help out, or they know that sustainability is something they should be caring about but just don’t take the steps to change their habits,” Zanders said. “The key is actually showing people how big of an impact they can make on people’s lives and the environment.

In addition to addressing food equity issues, community gardens benefit the environment. For example, unused plots of paved land that would have caused polluted runoff into streams and rivers are often prime sites for community gardens. Other gardens serve to educate community members about the importance of local food, nutrient-rich diets, and biodiversity sanctuaries.

Gardens in Forsyth County — especially the new ones in East Winston – are educated and encouraged by members of the N.C. Cooperative Extension to use native plants and practice sustainable farming techniques.

“Community gardens are living labs,” Waters said. “We encourage our new gardeners to use crop rotation, native and pollinator-friendly plants, and zero pesticides.”

“I want Wake Forest students to realize that they are not only making a big difference in people’s lives — the people in East Winston.” Waters said. “They can also learn about the environment, and gain something from that, too.”

Waters continued: “Imagine if we could implement those practices in the large-scale agriculture industry, and if we could make community gardens more widespread. The environmental payback would be huge. We could feed the people in America who are still going hungry.”