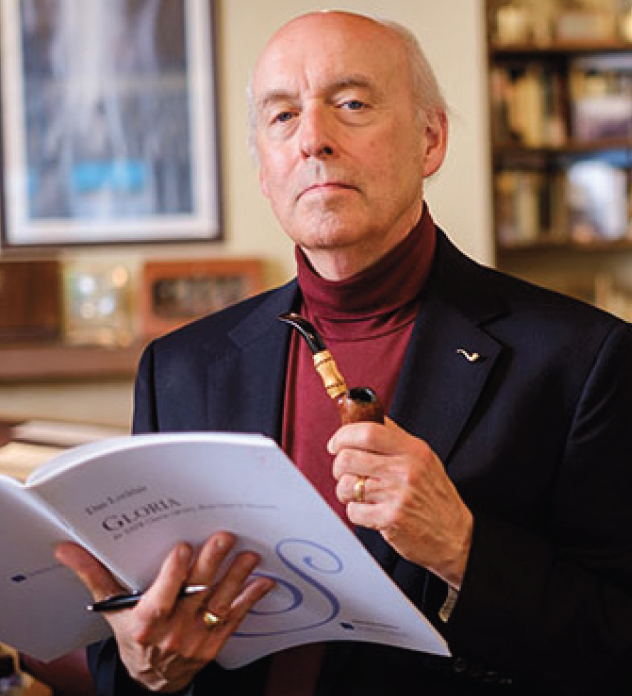

Deacon Profile: Dan Locklair

Locklair is Wake Forest’s composer-in-residence

Locklair poses with a composition.

March 24, 2022

Dr. Dan Locklair is a composer-in-residence and professor of music at Wake Forest University, joining the faculty in 1982. Originally from Charlotte, NC, his compositions are widely performed around the world, and he has won numerous music awards throughout his career, such as Composer of the Year in the American Guild of Organists’ centennial year (1996). On March 4, 2022, Locklair’s “Requiem” was released as an international album. Locklair will also be premiering a new composition in honor of President Wente’s inaugural ball on March 25.

How did you first get into composing? In other words, what is your history with music?

Well, I’ve always been fascinated by music. I had a passion for music early on. An uncle of mine, Wriston Locklair, was a music critic and a reporter for the Charlotte Observer. After doing that for a while, moved to New York City, where he wrote for the Herald-Tribune. When he left Charlotte, he left all of his library at my grandmother’s house, and that included all of the long-playing records that were sent for review, as well as books. So he told me, “feel free to take anything and listen to anything,” so I would go up into my grandmother’s attic and listen to recordings. That was my early experience, and that was even when I was in elementary school.

I was keenly interested in studying the piano at that point and also was playing the trombone. So, my aim, keyboard-wise, was to play the organ because the church that I grew up in had a lovely pipe organ. Very early on, I was invited to do some playing there. The long story short is I wound up getting my first professional job at age 14. That was really the beginning of my career because the organ is my primary instrument.

At the same time, I was keenly interested in creating music and was actively making notes on the page even as I was just starting to gain some sort of theoretical background on things. That was really the crux of it. I just had a passion for music. When I went to undergraduate school, I went into the field of the organ while also studying composition. I came to a position in Binghamton, New York.

In 1981, a life-changing sort of thing happened when I was still in Binghamton because I became one of the five winning finalists of the Kennedy Center Freedom Awards. That was a very prestigious thing, and I was the youngest composer to win that award. My work was performed on the stage of Kennedy Center, and it was broadcast worldwide by Voice of America and National Public Radio.

That was my first international exposure to music, and that was just one year before I joined the Wake Forest faculty.

What challenges have you faced as a composer, especially while balancing the role of a professor?

I would answer it first with just one word: time. I have been fortunate to have had almost an uninterrupted string of commissions since 1982, which all have deadlines. If you’re doing an orchestra piece, that can take a year out of your life, but you’re given a deadline when that piece has to be delivered to that orchestra so that rehearsals can begin, and then the performance of the premiere of it is already advertised.

In terms of teaching, I like to think of doing everything equally well. I carry a full faculty load, and at the same time throughout the year, I’m writing music. Yet, we all have the same hours in the day.

I was fortunate to be able to learn time management very early on and largely because of my uncle Wriston. He taught me by his example that you must be organized and efficient in what you do. I just like to make sure that everything is done with straight passion.

What work went into creating your recent international album release?

When an album like that is released internationally, every project that is done, no matter what label it’s in, has to have funding. The funding has to be secured, first and foremost. The art has to be there, though, too.

This particular recording centers around my “Requiem.” “Requiem” is a very large-scale piece. A requiem is basically a Catholic tradition; it is a piece of music that celebrates the dead.

My “Requiem” was composed in memory of my parents. This piece was premiered in 2015 in Winston-Salem, and I knew at that point that piece needed to have a really outstanding commercial recording. It was a wonderful premiere here, but it needed to have that international presence.

You need to have outstanding performers who say, “we want to record that.” And that is exactly what happened with the conductor of the Royal Holloway choir in London.

Rupert Goff, who’s one of the most respected choral musicians in Britain had said, “I want to record this,” then we talked about what else should go on the recording. We decided six of my other choral works would be on the recording. So you decide that sort of thing along with trying to figure out how much is this going to cost.

For over three years, all of that was actually in the works. It was postponed twice, and it was finally recorded last summer. This particular recording was done at Christchurch Priory in Dorset, England. The choir had to first learn all of the music. Everyone had to learn all the material that could come out, and you had this intense three-day period where you are under the microscope to make sure that every nuance and every note is as perfect as can be. And, obviously, you don’t always get that on the first tape. So the point is, making a recording is a long artistic product.

What is your favorite piece you have composed, and why?

It’s difficult to choose because obviously when you create something, at least for me, I have to feel very strongly about it. But, there is a piece on this album that is very close to me, besides the “Requiem.” It’s the piece, “Comfort Ye My People,” and I did it for my wife’s birthday.

That word comfort is such a word that so many people are drawn to, especially coming out of a pandemic and with the tragedy going on in Ukraine. This piece was already published even before the recording was made. I got emails from our members about the impact of that piece.

When you compose, you have to first move yourself with what you’re doing. You create an expression that you genuinely feel. But the ultimate feeling is when you find that you have moved someone else.

It’s sat in a hymn that is often played very rigorously, and it means that the words take on a different connotation. When I looked at those words fresh, the connotation to me was completely different. But that’s one piece on this CD that brought tears to the eyes of performers during the time that we made it.

How are you coming up with the composition for President Wente’s upcoming inauguration? What work goes into creating a commissioned piece for such an event?

The committee had asked me, because of my role as composer-in-residence, if I would agree to do a composition for President Wente’s inauguration that would be about three minutes in length. It would have brass, organ and percussion. I decided to do this festive piece and to call it “Fanfare Pro Humanitate,” because one, it is the credo of Wake Forest University. It’s a composition that starts out in a very long, linear fashion and it goes into a fast section, and then to a very triumphal mode at the end. So, it’s really a three-part piece.

I agreed to do it with great enthusiasm, because I’ve been involved in the planning and the execution of the music for the inaugurations of President Thomas Hearn and President Nathan Hatch, and it gives me great pleasure to be involved with the inauguration of a third president. I was very eager to do that, and I will be conducting it. I have commissioned from all over, but there’s something very special about doing something on the turf where you spend so much of your life teaching and where you know so many colleagues and students. So, to be able to do this piece attributed to this very important inauguration and this new chapter really means a great deal.