Zerwick talks ‘Beyond Innocence’ at law school event

Panelists discussed the case of Darryl Hunt and North Carolina’s criminal justice system

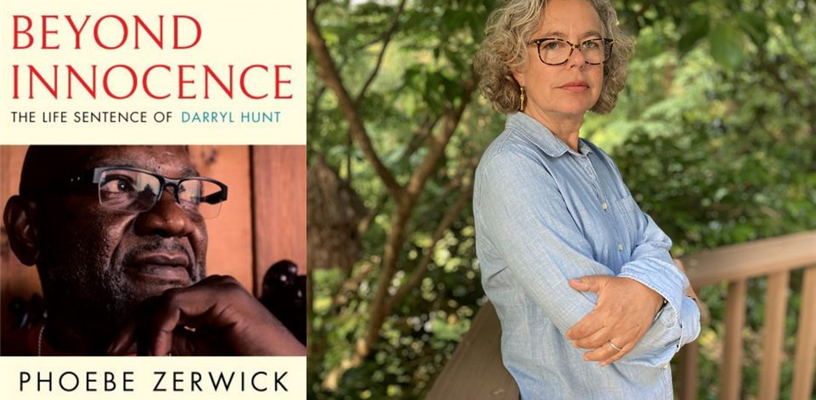

Courtesy of Forsyth Central Library

Zerwick’s book covers the case of Darryl Hunt, who was exonerated for murder.

October 6, 2022

The Wake Forest University School of Law presented a panel discussion entitled “Beyond Innocence: Darryl Hunt and the Fight for Justice in America” on Sept. 29. The event recounted the Darryl Hunt trials through the introduction of the Wake Forest Hunt Trials Collection — an archival collection housed in the School of Law — and conversation surrounding Professor Phoebe Zerwick’s book, “Beyond Innocence: The Life Sentence of Darryl Hunt”.

Darryl Hunt — a Black man from Winston-Salem — was wrongfully convicted of the murder of Winston-Salem Sentinel journalist Deborah Sykes in 1994. He served nearly 20 years in prison before being exonerated. After his exoneration, Hunt went on to be an advocate for social justice.

Panel host Corey D.B. Walker, Professor of the Humanities in the English Department and director of the African American Studies Program, introduced the three panel speakers — Leslie Wakeford, Metadata Services librarian and archivist, Zerwick and Hunt’s attorney Mark Rabil, clinical professor of law and director of the Innocence and Justice Clinic at the Wake Forest School of Law.

The event highlighted that it takes a village to fight for what’s just and that through the efforts of so many, Hunt’s story will live on forever, and hopefully help others in their fight for justice.

“And one day, the Winston-Salem Five, just like the exonerated five in New York, will be the exonerated Winston-Salem Five because of Darryl Hunt’s case, because of the work of the innocence inquiry commission and because of a librarian in the archive,” Rabil said.

Walker first asked Wakeford to detail Hunt’s archive, the Wake Forest Hunt Trials Collection, which is stored at the Wake Forest School of Law. The archive is comprised of all the materials Rabil collected during the 20 years he represented Hunt as well as material following Hunt’s exoneration.

“It was an avalanche of material — 30 boxes, giant three ring binders, at least 25 or 30,” Wakeford said.

The conversation was then directed to Zerwick, who first wrote about Hunt’s case in the Winston-Salem Journal but felt inclined to write more about his case after his death. She wanted to detail what was going through Hunt’s mind between 1994 and 2004 — the 10 years of courtroom defeat despite the DNA evidence that showed he didn’t murder Sykes.

During the panel, Zerwick said, “The man (Hunt) who at 19 had assumed that if he simply told the truth he’d be released was wiser now, he had spent countless hours in prison studying his case files, reading the law and learning how structural racism was ingrained in American history — in his history.”

She continued: “ . . . entries that discussed the conditions he saw around him as a form of social control, even genocide. In his plight is that of a political prisoner. Inside prison, it was clear that the tough on crime policies enacted on the outside were causing unimaginable and permanent harm to the hundreds of men in prison with them.”

Zerwick highlighted letters from the archive that Hunt wrote to Rabil from prison — many of which described the legal system as racist and the prisons as harmful.

Despite his wrongful imprisonment, though, Hunt stayed faithful.

“This latest injustice has taken me a long time to accept that the highest court in North Carolina could make such a racist political ruling,” Hunt said in a letter. “I thought the worst was over after Judge Morgan’s rule, however, I haven’t given up. I believe strongly that God will bring about justice.”

Rabil then spoke, describing Hunt’s case as “the case.”

“So to me, this case, Darryl Hunt’s case, was the case,” Rabil said. “That is the case in terms of American justice, in terms of Black men and women in America. There is no other case and there are all the other cases that are wrapped up in this one there.”

The rudiments of the legal system in the United States might establish that everyone is innocent until proven guilty, except, according to Rabil, everyone really presumes that you’re guilty. Rabil emphasizes the importance of preserving Hunt’s case and reaffirms the misconception of presumed innocence, asserting that if people are guilty until proven innocent, there should not be a presumption of imprisonment.

“So, presumption of innocence, means get rid of the presumption of incarceration,” Rabil said. “So I have faith that my students, I have faith that this archive can tell these stories. And as we move forward, we can bring back and fully from the presumption of innocence.”

Among the audience were Hunt’s wife April Hunt and Kelvin Alexander, one of Rabil’s clients who, like Hunt, spent 28 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. Two of those years were spent at the same facility as Hunt.

Before the conclusion of the event, Walker welcomed Wakeford back to the discussion to present the finalized aided inventory posted by ZSR Special Collections and Archives which documents a detailed collection of a series of documents, historical notes and newspaper articles, to name a few, of the Hunt case online.

The event emphasized that Hunt’s story will persist and be used in the fight for justice. It will continue to bring to light cases in which the legal system failed individuals and misconceived the presumption of innocence.

“His story is going to be told and help other cases. I’m happy about that,” April Hunt told the Old Gold & Black.