On appreciating pop music

What ‘Tom and Jerry’ and Drake taught me about the arts

March 15, 2023

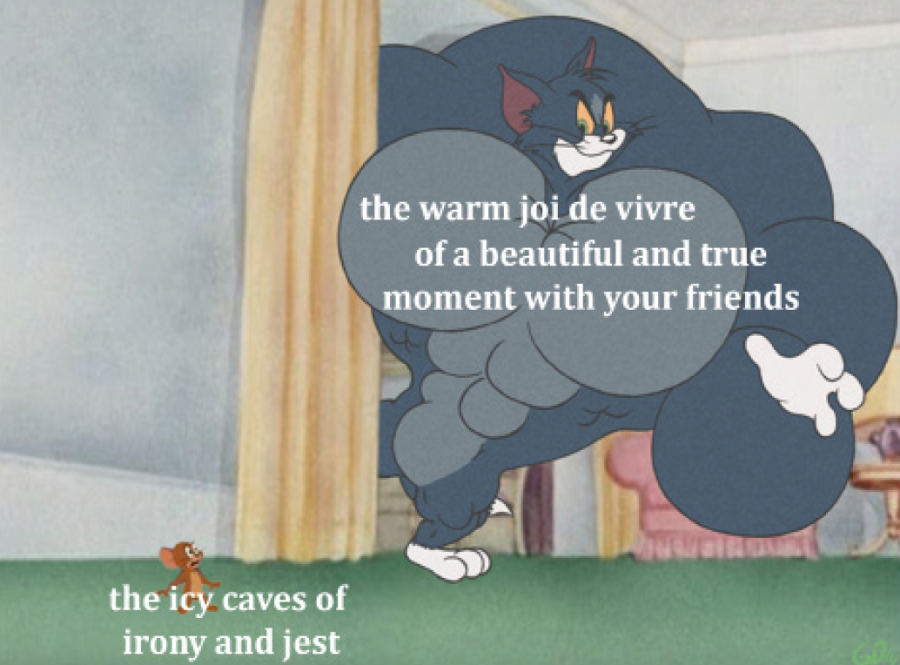

“Tom and Jerry” is comedic perfection. Way back in the mid-2000s, I adored the recyclable premise and the over-the-top gags to the point where I would stay up past my bedtime and sneak into the living room to catch the reruns. “Tom and Jerry” is also undoubtedly a kid’s show. So you can understand my surprise to find myself sitting on the couch with my friends in 2023, all of us watching a cunning mouse evade a tenacious, if unlucky, cat for seven-minute intervals. Even more surprising is that we really enjoyed it.

I can posit with certainty that, had none of us ever watched the show before, Jerry’s narrow escapes and Tom’s beatings would not have been nearly as entertaining. Because while I will push back on anyone who argues that “Tom and Jerry” is not a quality show in its own right, I have to admit there is something magical happening behind the scenes that has nothing to do with the program, really. Because even while sitting on a couch in Colorado in 2023, a small part of me is actually in a dark living room in Ohio, transfixed on the bluish glow of a 120-pound TV, worrying that the vague creak I just heard may or may not be Dad walking downstairs to tell me to go to bed.

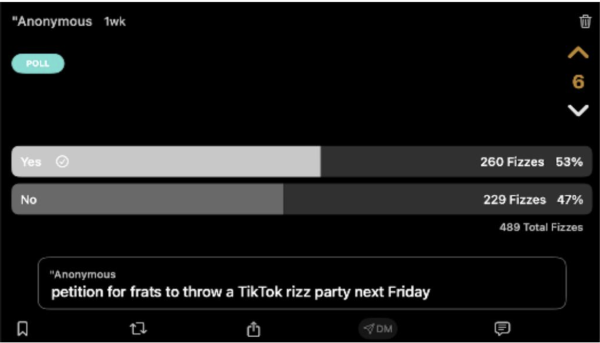

There’s something like this “Tom and Jerry” phenomenon going on in popular music, too. After all, it is hard to stake a real claim for any kind of timeless genius being intrinsic to the most successful pop songs. There’s the problem of commercialization and the industry’s power to skew art toward a profit motive. There’s also the vapidness of the lyrics — the ones that often glorify wealth and sex and sometimes are simply misogynistic.

But there is a fascinating and complex aspect to pop music that I am embarrassed to have overlooked for so many years. Pop music has the luxury of not needing any staggering depth or awe-inspiring sounds since the communal experience of bonding over a piece of art is more beautiful than any artistic masterpiece could possibly be.

There is a fascinating and complex aspect to pop music that I am embarrassed to have overlooked for so many years.

It is a beautiful and vitalizing thing that I can read James Joyce and feel like I’m really talking to someone — like I’m a little less alone. It’s also perverse and pernicious to deem that kind of art as more powerful than dancing around the kitchen with your friends, singing along to “Nice For What” or “Doo Wop” or “Get Lucky” or “family ties.”

To do so is to totally miss the point and forget that, at the end of the day, art is about humanity.

It has not been, nor will it ever be about the song itself, really. What matters is the shared experience, the total surrendering of the self. Music becomes this vessel through which an otherwise impossible connection can be formed. It is a powerful sense of belonging and communion. Is it any wonder that concerts and certain religious services sometimes feel eerily similar?

No song exists in a vacuum. It is where you were and who you were when you first listened to it. It is all of those moments in which you grew more familiar with it, and it is right now, as you are surrounded by other people who have also experienced the song. The fact that a certain song or artist can capture the zeitgeist of a generation or tether people together like children crossing the street is wonderful. Sure, there is a zero-denominator quality to this phenomenon as well, but a part of me also respects a song that has no barrier to entry — that meets everyone right where they are.

I guess what I’m saying is, if you’re someone like me — a person who used to scoff at pop music — you might find it worthwhile to ask yourself whether anything can be gained from all the criticism and iciness, or if something is only lost.

Of course, I didn’t always see music this way. I have been one of pop music’s most tenacious critics over the years. I’ve learned recently that it is easy to be cynical, but it is also unrewarding and self-destructive. Creating art is difficult, but that is where all of life’s spirit can be found.

I guess what I’m saying is, if you’re someone like me — a person who used to scoff at pop music — you might find it worthwhile to ask yourself whether anything can be gained from all the criticism and iciness, or if something is only lost.