On July 10, Wake Forest Properties partnered with Yadkin Riverkeeper, a non-profit of water keepers and advocates, to install Asheville GreenWorks’ Trash Trout, which will collect trash, plastic waste and debris found within Silas Creek in Reynolda Village.

The partnership, which initially began in September 2022, will help clean and begin microplastic research of Silas Creek, with Yadkin Riverkeeper leading the volunteer sign-ups and maintaining the Trash Trout site. Yadkin Riverkeeper is one of 15 riverkeepers within North Carolina that cleans, advocates and studies different tributaries and watersheds.

The Trash Trout, like the one in Silas Creek, is the lovechild of Asheville GreenWorks and North Carolina Attorney General’s Environmental Enhancement grant. In 2000, the N.C. hog production giant Smithfield Foods entered a 25-year agreement with the state of N.C. to fund $2 million a year to various environmental enhancement projects pertaining to air, water and land quality across the state. As part of this grant, 15 N.C. riverkeepers from Waterkeepers Carolina received funding towards microplastic research and installing Trash Trouts in their watersheds. GreenWorks, a non-profit that works to create a “climate-resistant community for all,” designed and produced the Trash Trouts.

Edgar Miller, the executive director and riverkeeper of Yadkin Riverkeeper said that the grant aimed towards understanding the microplastic levels and trash within smaller tributaries across the state.

“The real goal of that was to identify whether or not you know how well these [trash trouts] work did removing trash, but we were also taking samples for micro plastics,” Miller said.

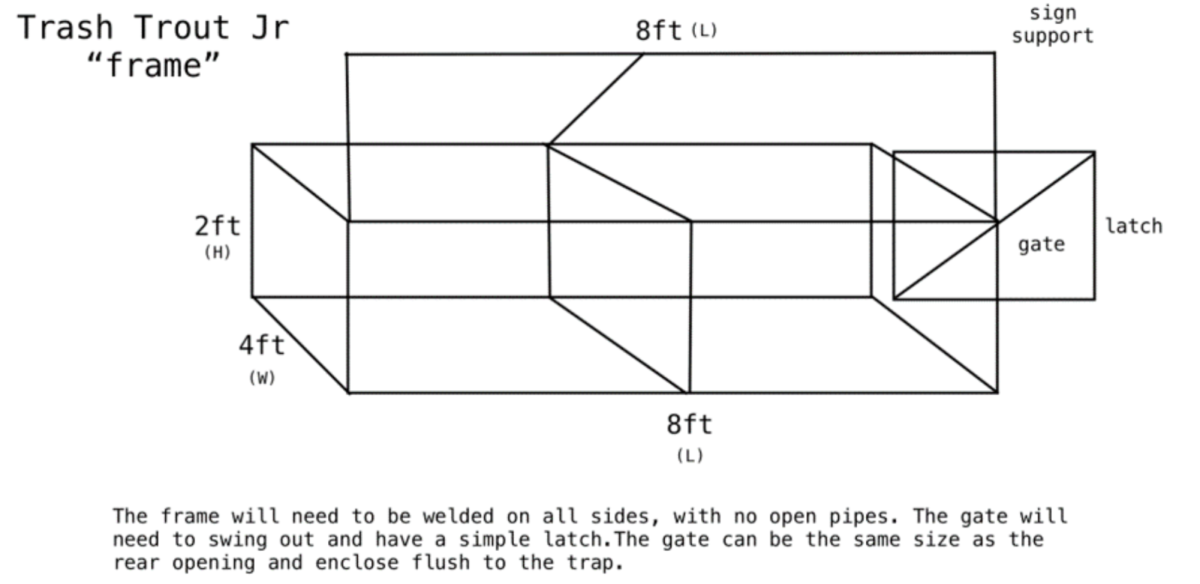

Grace Fuchs, the Yadkin Riverkeeper Assistant from September 2021 to this August 2023, describes the Trash Trout as a colander. The Trash Trout, with silver aluminum circular pontoons encases a silver fence frame with an open top and bottom. The fence material allows for water to flow through the Trash Trout but catches the trash like pasta strained through a colander. The Trash Trout is anchored on both sides of the creek bed with steel cables. On either side, line buoys funnel the trash into the trap. The amount of trash collected in the trash trout depends on the watershed flow rate. Meaning, with more water flowing, more trash is picked up and pushed down or upstream. The trap itself is also climate change resistant with the Trash Trout unhitching and moving to the side of the creek in case of heavy flow rate or fallen tree limbs.

GreenWorks initially began the Trash Trout project in 2015 with hopes to halt trash polluting in smaller tributaries before reaching larger bodies of water. In addition to cleaning watersheds, they wanted to build more awareness of water pollution within communities and municipalities. After two years of research, GreenWorks partnered with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and installed their first trap in 2017.

Eric Bradford, the director of operations at GreenWorks, said that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife partnership helped GreenWorks’ Trash Trout design not only be effective but safe to wildlife and other ecosystems within tributaries.

“[The partnership] really helped us design what [the Trash Trouts] are today, creating it the way it is with no top, no bottom on the trap,” Bradford said. “The size of the openings, for the sieve that’s on it, is important as well. The way [the Trash Trout] operates, the way it sits in a creek, all of those things were informed through working with partners like U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and also with local engineering firms, so we could come up with something that’s simple but effective.”

GreenWorks offers two Trash Trouts: Trash Trout, which is 21 feet by 12 feet and can sit in a 200-foot wide stream, and then Trash Trout Jr. (the one located in Silas Creek), which can sit in a creek 50 feet wide.

Silas Creek’s Trash Trout installation took six hours with volunteers from Yadkin Riverkeeper and GreenWorks measuring the creek and cementing the Trash Trout properly onto the bank. The stream morphology and size was important in choosing the location for the Trash Trout, as installing trash trouts requires certain creek creeks and needs to be visible and away from outdoor water activities such as paddling or kayaking.

“It’s a bit of a process back and forth, making sure that we find the right [location] because, you know, all of those tributaries have their own personalities and have their own challenges,” Bradford said. “We’re basically doing something that’s not really a paved path for us here. We’re blazing forward each time that we do this. Each installation is different.”

While the Wake Forest location proved to be the best of both worlds for size, visibility and education purposes, Wake Forest Properties was not Yadkin Riverkeeper’s first location choice. According to Miller, they initially looked into streams throughout Forsyth, Davidson and Rowan county to find the right stream size for the trash trout. Miller originally identified Peter’s Creek near Hanes Park in Winston-Salem as a potential location. After some back and forth discussions with the city, Winston-Salem raised some issues with the insurance, liability and monitoring of trash trouts, according to Miller. Miller and his team responded and after some discussion, Winston-Salem responded “not at this time.” and Yadkin Riverkeepers switched directions According to Miller, there was no formal request or proposal submitted or denied by the city, but in short, they did not receive permission to install the trash trouts. The Yadkin Riverkeeper pivoted and reached out to Wake Forest Properties in September 2022.

Jodi Tonsic, the director of marketing at Reynolda Village Wake Forest Properties, led the Trash Trout initiative alongside Jenny Bush, the assistant director of Wake Forest Properties.

“We’re very committed to sustainability efforts and to trying to preserve the beautiful property that was the Reynolda estate,” Tonsic said. “We were also interested – Wake Forest being an educational institution – in any possible things that Yadkin Riverkeeper could learn from having [the Trash Trout] installed on our property.”

As apart of discussion with Wake Forest Properties, the Yadkin Riverkeepers signed a standard Property Use Agreement which according to Tonsic, “requires third parties conducting activities on our property to have liability insurance to protect the University from personal injuries and property damage that might occur related to those activities,” Tonsic said.

Yadkin Riverkeepers in accordance with the contract and Wake Forest University’s requests provided a COI [claim of insurance] of $1 million and added Wake Forest Properties under their insurance policy in case of damages to others or any other property from the trash trout.

While Trash Trouts help riverkeepers keep track of trash, they also allow for research and education in the community. Madison Sings, GreenWorks’ watershed outreach coordinator and Yadkin Riverkeeper both rely on the help of volunteers to host cleanups in watersheds and with Trash Trout. In Asheville, Sings trains volunteers in cleaning up the trash courts while scheduling work days for volunteers and students.

“We look for people who we can empower to become a part of the educational component,” Sings said. “We’re educating our stream keepers about the local waterways, and they become empowered by the information they’re learning to go out and tell other people.”

Fuchs says that Trash Trouts not only mitigate trash reaching the ocean, but also show the quality of our waterways. Although the Trash Trout gathers trash like plastic and styrofoam, watersheds, like Silas Creek, are still at risk from microplastic contaminating the water. In her sampling of the creek at Reynolda Village, Fuchs found particles of microplastics.

“It’s not that far from [Wake Forest’s] campus,” Fuchs said. “There are still pieces of microplastic in [the creek] already. That’s only going to increase as you go further down the river system, and there’s more and more trash.”

Fuchs continued: “What we do in [Winston-Salem] has an impact on downstream users of the river. Surprisingly, a lot of people don’t know where the Yadkin River is, or that it’s our drinking water source here in Winston-Salem.”

Bradford reiterated Fuch’s sentiments, stating that while the traps help facilitate cleanups, they also open conversations regarding waste in communities.

“We want to talk about where the trash is coming from, and what are some of the sorts of things that we can do to support this on a state level,” Bradford said. “Is it a bottle bill? Is it something local in your particular county that you can do that can limit where the trash is coming from? Is this enforcing certain ordinances that you have in your county that you’re just not currently doing?”

He continued: “There’s a whole myriad of things because, yes, it’s great to put the traps out there. But for us, we want these folks to know that they’re part of a bigger network, and we can work with this network.”

Although the 39 Trash Trouts installed across five states are efficient in collecting trash, volunteers are needed to continually check and clean out the Trash Trouts. For students, Fuchs advocates for people to start small and limit their plastic waste to mitigate debris in watersheds. Both Sings and Bradford also recommend students interested in engaging with Trash Trouts or interested in water cleanups to reach out to Asheville GreenWorks.

Brian Cohen, the assistant director of sustainable engagement at the Office of Sustainability at Wake Forest, vocalized hopes for potential student involvement and engagement in the future.

“The Office of Sustainability is always open to partnerships and for supporting the great work that local organizations such as Yadkin Riverkeeper are doing to improve the health of our ecosystems,” Cohen said. “While I’m not sure if there are volunteer opportunities around the Trash Trout specifically, we definitely hope to get more students out into the wetlands to see how human and hydrological processes interact and to help keep the area as healthy as possible.”

Miller says that volunteer efforts and the need for volunteers is slow, as the trash trout hasn’t collected as much trash due to the flow rate. In the future, if students want to get involved with volunteering at Yadkin Riverkeeper or cleaning out the trash trouts, they can contact them via their website.