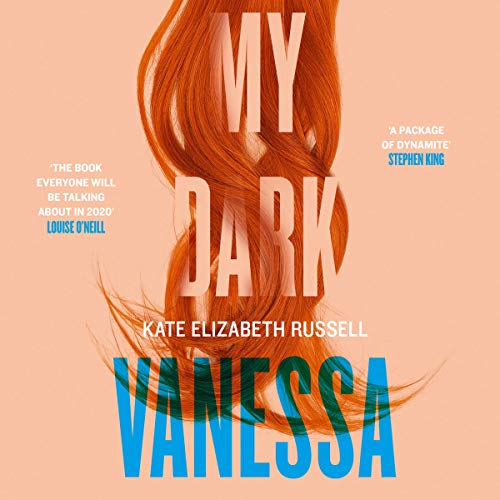

BookTok. A force greater than any literary publication of the last quarter century. On TikTok, young women speak earnestly and anxiously about the next book you need to read. It is quite possibly a force that will redesign the priorities of publishers and authors alike. In recent years, social media has greatly diminished the role of critics as the gatekeepers of good taste, and as a result, new genres of thought are emerging as the houses of yore scamper to keep up. “My Dark Vanessa” is one such case.

The debut novel of author Kate Russell caused a stir upon its 2020 release. It was added to Oprah’s Book Club list and quickly removed following unsubstantiated reports of plagiarism. Written as a companion piece to Vladimir Nobakov’s 1955 novel “Lolita,” a book fraught with controversy, Russell evidently decided that controversy was exactly what she wanted.

The novel takes place in the year 2000 at a prestigious Maine boarding school where the titular character, 15-year-old Vanessa Wye, becomes intimately involved with her 42-year-old English professor. This setting is intermixed with scenes of Wye in 2017 as an adult reckoning with the #MeToo movement and her complicated perception of consent and relationships.

It would be easy to say this is a book about the over-sexualization of girls — and it is. But, more importantly, it is about why we as a society are okay with that. It is about why “Lolita” is still misread as a love story, why girls are taught to crave the validation of older men and why we don’t speak out.

What it means is that we are pushing for a future in literature that allows women the full range of emotions and actions that male characters have had since the Gutenberg printing press was invented.

Wye is not particularly likable. She is a loner who listens to Fiona Apple and views herself as an intellectual outsider. Throughout the novel, she refuses to accept that she is a survivor of grooming and scoffs at the mass culling of predatory men — but we need more protagonists like Wye. The denial she experiences throughout the book exemplifies how we teach young girls to feel — that older men are wise and must think you are special, they know what is best and it is sexy and mysterious to be youthful yet sad.

The experience of grooming is complicated, and Russell doesn’t shy away. Wye cannot live without deluding herself, stating, “Because even if I sometimes use the word abuse to describe certain things that were done to me, in someone else’s mouth the word turns ugly and absolute. It swallows up everything that happened.”

It is the harsh truth of how we survive through such horrible things. Nothing in our society tells us it is explicitly wrong until the onus is on the victim to get over it. Messaging between predatory older men and younger women is persistent in our films, commercials, books and social media, yet we wonder why it still happens.

Maybe that is why the young women’s army on BookTok is talking about it. They are reading books like “My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” “The Virgin Suicides,” “Everything I Know About Love,” “The Bell Jar” and “Normal People.” They are tired of likable female protagonists and ask us, “Why is the highest compliment a woman can receive is that she is likable?”

The denial she experiences throughout the book exemplifies how we teach young girls to feel — that older men are wise and must think you are special, they know what is best and it is sexy and mysterious to be youthful yet sad.

Instead, they want to see the less likable parts of themselves reflected on the page, the parts that are evil and malicious, and the parts that want retribution for men’s wrongs. “My Dark Vanessa” tells an uncomfortable truth — we cast judgment on who is a good survivor and who is a bad survivor. Wye voices this cruel reality, questioning, “I wonder how much victimhood they’d be willing to grant a girl like me.”

I will not claim that this is not a disturbing novel. It is. It made my stomach hurt and left me on the verge of tears. We live through Wye’s thoughts and terrible rationalization of her own grooming. We see how the relationship destroys her ability to be a functioning member of society and an adult woman — but it is important.

Russell reads to me like a Lana Del Rey-adjacent thinker. Like Del Rey, she gives the narrative power of imbalanced relationships back to women. Rather than stay in the mind of the assaulter, we get to know how Wye feels. With a critical eye on how “Lolita” has left an impact on literature forever, she has the ability to sit and stew in the discomfort of injustice. Russell is honest about the sickly perception of girlhood and the desire to feel incapacitated by it.

“My Dark Vanessa” speaks to a greater cultural moment we are experiencing. There is a saying among book lovers that, “we support women’s rights and women’s wrongs.” What it means is that we are pushing for a future in literature that allows women the full range of emotions and actions that male characters have had since the Gutenberg printing press was invented. So here’s to more Lady Macbeths, more Daisy Buchanans and more nuance to our female characters.