Amy Catanzano is an associate professor of English in creative writing and the poet-in-residence at Wake Forest. On Wednesday, Jan. 31, she streamed her talk titled “Quantum Poetics: On Physics and Poetry,” which emerged from her upcoming book, “The Imaginary Present: Essays in Quantum Poetics.” She then answered questions during a live, virtual Q&A session.

Catanzano’s work, which she broadly refers to as “quantum poetics,” combines quantum physics — the study of matter at the sub-atomic level — with poetry to produce a variety of writing from poetry to essay to memoir. She is particularly interested in the potential that theoretical physics creates for new modes of artistic expression.

While Catanzano is primarily a writer and professor of creative writing, she has dedicated much of her life to studying and researching physics. Such scientific inquiry has led her to collaborate with renowned scientists at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Switzerland, the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile and the Simons Center for Geometry and Physics in New York. She is “especially excited by the cutting-edge fields of quantum computing, high-energy particle physics and astrophysics.”

The talk began with a meditation on time, which did well to set the stage for what was to follow. Catanzano declared that “one doesn’t need to be a poet or a scientist to get the sense that time is not what it appears to be,” but that poetry and physics are quite alike in their ability to challenge normative temporality. While breakthroughs in physics like Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity have effectively demonstrated the subjectivity of time, a poem can make a reader feel that instability.

“Ordinary conceptions of time must be revised in order to account for the discoveries that have been made by scientists about our universe,” Catanzano said. Poetry is an effective tool for such revision.

Physics and poetry are often understood as disparate fields on polar ends of the sciences-humanities spectrum, but Catanzano’s work illustrates the complementary nature of the two. She spoke about how she has come to understand physics as a philosophical and cultural discourse — one that is constantly reinventing and challenging itself.

“Quantum poetics [posits] that quantum theory is encoded in and by artistic practice,” she said.

The influence goes both ways.

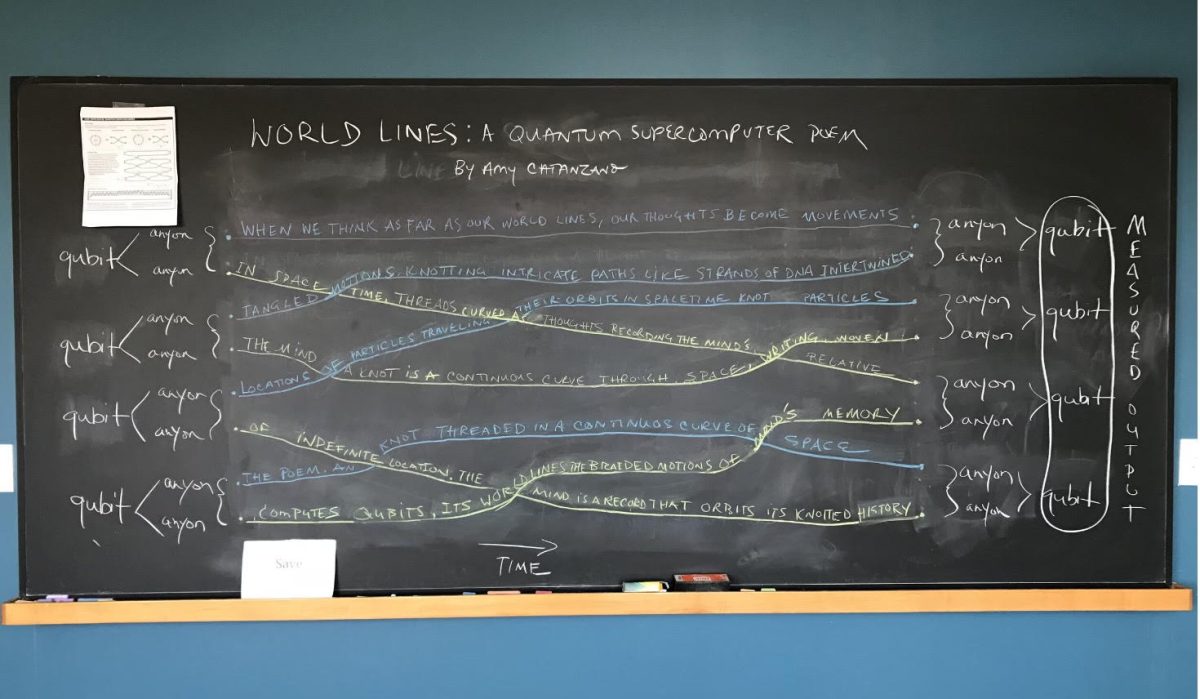

Quantum poetics is rooted in a rich tradition of artists responding to scientific paradigm shifts around them. Yet Catanzano believes that quantum poetics “departs from some of the conventions of this tradition by ‘heading off the grid altogether.’” Quantum poetics does not simply allude to scientific research; the two are completely intertwined. One such instance is Catanzano’s poem “World Lines,” a quantum supercomputer poem.

“World Lines” contains lines of poetry that criss-cross over top of one another. At these intersections, the lines “share a word where ordinarily a quantum knot would be produced in a topological quantum computer. The reader can read the poem in a linear way or choose a branch of poetry to follow when they get to a shared word.”

Catanzano knew that there were multiple poems within the poem existing in a state of quantum superposition — but she did not know how many. That was until she collaborated with Michael Taylor, a computer scientist who created an AI that, thus far, has found over a thousand distinct poems within “World Lines.”

One might wonder what poetry can do for a robust field like physics — how can poems impact a scientific discipline built on real-world experiments and mathematical proofs? According to Catanzano, poetry “is especially poised to respond to a question that science on its own has been unable to answer. That question is: what does quantum physics mean?”

Poetry, with its endless freedom, gives us the necessary outlet to grapple with the ramifications of quantum physics as well as imagine the new doors it can open for us. Via poetry, written and spoken words take on the role of “physical manifestations of possibility in potentia, the imagination made material.”

After the talk concluded, Catanzano pivoted to answering live questions from the comments section of the video. The audience’s reception was ecstatically positive as dozens of questions poured in — not due to confusion but curiosity. Quantum physics and avante-garde poetry are liable to be inaccessible to the general public, but Catanzano’s talk was easy to follow without sacrificing much of its complexity and nuance.

If the questions directed toward Catanzano after her talk can confirm anything, it is that many viewers walked away having learned a great deal, but still they were hungry to discover even more.

Correction Feb. 26: A previous version of this story contained minor errors in quotes from Amy Catanzano. These have since been corrected.