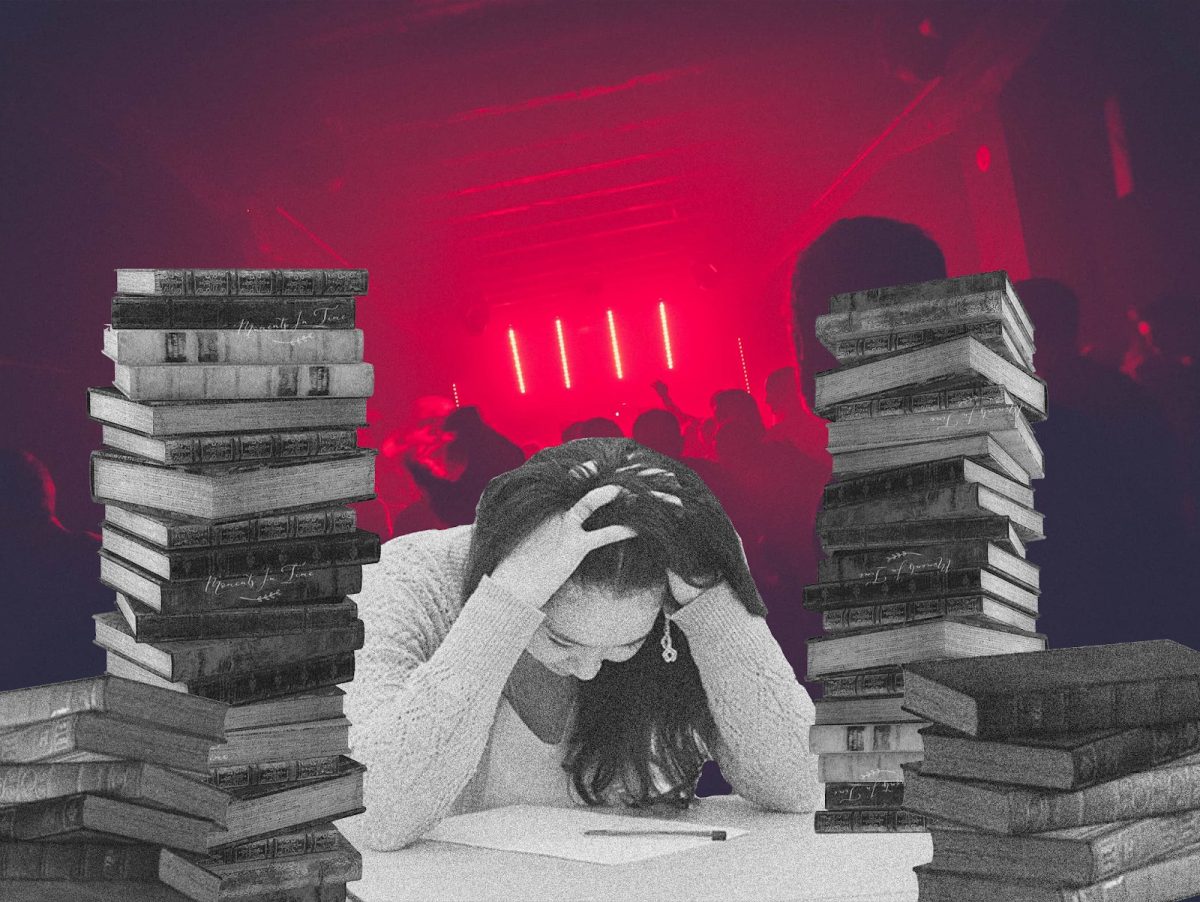

Wake Forest University is full of smart, capable students who are accustomed to academic perfection — that much is undeniable. Yet, the fact remains that Wake Forest and its students are not immune to the recent trend of grade inflation that has gripped higher education and shows no signs of letting up.

Wake Forest is playing catch-up

GPA standards that used to accurately reflect academic performance have become increasingly irrelevant as GPAs rise across the board. This dilemma is playing itself out in the debate on campus regarding Latin honors distinctions, which up until the Class of 2024, were awarded on an escalating ladder of GPA benchmarks.

Now, however, such honors will be decided by GPA percentile. While the change is rattling students’ feathers in the Class of 2024, it is long overdue and much-needed.

Wake Forest is not leading the charge against mandated GPA limits. In fact, the school is playing catch-up. As Provost Dr. Michele Gilespie, who was dean of the college when the change was voted on, noted, Wake Forest’s peer institutions have already adapted their requirements to the current inflationary environment. Wake Forest is simply getting with the program.

Nor is there a basis for student complaints about being surprised and needing to adapt to the change. The policy has been publicly available since current seniors first stepped onto this campus as freshmen in Aug. 2020.

Whether students like it or not, something had to change

Students worry this updated policy is a bad policy, and such concerns deserve to be taken seriously. However, the rationale must first be explained.

Grades are increasingly less useful at distinguishing between excellent and average student performance. The signaling value of an A is undermined if A’s are ubiquitous.

— Vikram Mansharamani

Until 2019 (at the latest), the GPA limits functionally acted as proxies for percentile markers, which is common practice; e.g. at Wake Forest, a 3.4 GPA constituted approximately the 70th population percentile, a 3.6 GPA the 85th percentile, and a 3.8 the 95th percentile.

Grade inflation invalidated this structure. The trend of average undergraduate GPAs rising year after year is not, surprisingly, the result of a more capable student body. Instead, the most plausible explanation is that grade inflation is the result of shifting academic norms about success combined with students’ incentives to avoid tougher-grading STEM majors to create a cycle of ever-improving grades. As grade inflation starts, so it spreads — colleges have no reason to place their students at a disadvantage as grades rise and employer expectations rise with it. As such, it becomes a collective problem that no one school can solve on their own yet higher education as an industry has no incentive to redress.

“Grades are increasingly less useful at distinguishing between excellent and average student performance. The signaling value of an A is undermined if A’s are ubiquitous,” Vikram Mansharamani writes.

Since Latin honors were given out by passing increasingly obsolete GPA markers, these distinctions follow the same deflationary value logic as grades. Under the old system, Latin honors no longer served as representative markers of academic excellence.

As a result, there were two pathways forward to retain the elements of exclusivity that make Latin honors prestigious — either Wake Forest could raise hard GPA cutoffs each year to account for grade inflation (essentially taking the 70th, 85th, and 95th percentile GPA of the previous graduating class or current class as juniors) or eliminate all that unnecessary work and set the limits as percentiles instead of hard numbers.

They chose the latter.

Clearly, something had to change. But students rightfully wonder if explicitly pitting students in competition with one another for Latin honors will have a cultural effect on an already competitive campus.

Yet it seems unlikely that the student body will ever abandon the “Pro Humanitate” orientation that has successfully guided generations of students to success. Supporting our peers is not mutually exclusive with academic achievement. In fact, the opposite is more likely to be true — having a strong mutual-support system is a competitive advantage in a high-stress environment like Wake Forest.

This policy resolves Wake Forest’s ongoing problem with grade inflation but also poses novel questions for the campus community regarding added pressures to perform. Unfortunately, it also leaves existing questions unaddressed.

Students majoring in difficult subjects will subsequently be at a disadvantage

This policy does not go far enough in equalizing the rewards for majors that significantly differ in difficulty and grading practices. It is possible to acknowledge that some majors have it easier than others without disparaging each other’s academic choices. In any case, the statistics prove it.

Yale published a report detailing the percentage of A/A-’s received by students in each major. It was not a surprise to see Economics and Mathematics receive around 52% and 55% A/A-’s respectively, the two lowest percentages of any major. At the other end of the spectrum, Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and History of Science/Medicine each topped 90% A/A- scores.

While Yale is just one elite college, a broader study published in the International Journal of STEM Education found that “when comparing otherwise academically similar students, we find that STEM students have substantially lower grades and GPAs, and that this is the consequence of harder (more stringent) grading in STEM courses.”

All majors are not created equal.

If all professors (but especially those in STEM) graded on a curve, the GPA discrepancies would not be a problem. Alas, it remains a sobering reality that the students who pick the most difficult and not coincidentally, the most financially rewarding majors, lose out on major honors to students (like myself) who chose less difficult academic terrain to traverse during their undergraduate years.

Wake Forest should lead the way in rewarding exceptional students in difficult majors with Latin honors. By altering the population from the total graduating class to that of each major, and subsequently awarding Latin honors for the top performing students in each major, provided they hit a minimum enrollment, Wake Forest could incentivize achievement for all instead of the few.

Even if Wake Forest has to lower the class rank percentiles to retain prestige in the face of smaller populations, Wake Forest would be investing in their students’ success — an investment that’s sure to pay off.

Alums-r-sad • Mar 23, 2024 at 7:22 pm

Good job. Yet another reason for pre med, STEM, business and engineering minded applicants to stay away fromWake Forest University now. Not a great idea on top of the drop in USNWR, high costs of attendance and millions of dollars going not everything but more scholarships. Sadly, it appears there is a bloated sense of who Mother so Dear’s peers are nowadays as well.