In 1942, nearly a year after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, the United States was completely immersed in fighting World War II. College-aged men were getting drafted by the thousands, including male students at Wake Forest College (now Wake Forest University). The war in the Pacific and Europe sparked a battle within the Wake Forest community.

Dr. Thurman Kitchin and the Board of Trustees had to decide whether to let the school collapse in financial ruin or to accept female students. Since 1834, Wake Forest had been operating as a male-only school.

Many opposed co-education because they believed that a Wake Forest was only suited for men, and female students would be inappropriate for the setting. Others were open to the idea as it provided a way to keep reproducing Baptist families.

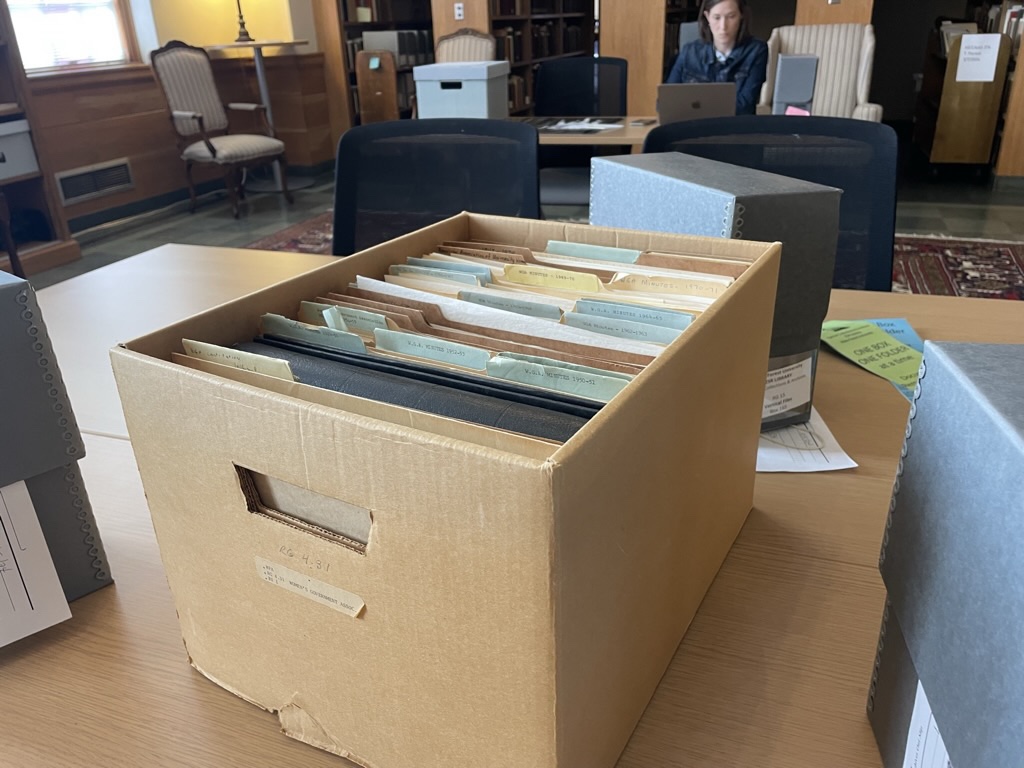

“Some say they object to co-education because the boys and girls will fall in love. What’s wrong with that?” wrote Kitchin in the excerpt of a letter obtained in the ZSR Archives by the Old Gold & Black. “Boys and girls who attend the same school usually come from the same stratum of social and economic life, have generally the same tastes and attitudes and all in all have less adjustments to make.” (Editor’s note: The Old Gold & Black could not confirm who the letter was addressed to.)

The Board of Trustees met on Jan. 15, 1942, and “after deliberate consideration,” resolved to allow women who were upperclassmen to attend Wake Forest for the duration of the war. After discussing with many prominent Baptist men in the area, they ultimately decided that it was “educationally sound, financially economical and socially wholesome.”

By the fall of 1942, 53 women joined the Wake Forest student body with Lois Johnson, or “Miss Lois,” as the first dean of women, whose primary job was to be an administrator for female students.

Lois’s legacy

Johnson requested the formation of a separate student council for women at Wake Forest.

“In view of the fact that Wake Forest is now co-educational and that the women in college are governed by different regulations from the men, I should like to ask the Trustees to grant to the women students the right to make and enforce all rules which apply distinctively to them,” she wrote in a letter to Kitchin.

This request was granted, and the Women’s Government Association (WGA) was created in 1943.

Although all college-aged women were now allowed at the school, they were held to much higher behavioral standards than the men. Upon arriving on campus, they were given a “Handbook for the Women Students of Wake Forest College” in which the school’s expectations were outlined. Male students followed the “Wake Forest Student Handbook,” which only outlined expectations for men attending the college.

Their curfews were 10:30 p.m. on weeknights and 11:30 p.m. on weekends. They were not allowed to be alone with men or go on “dates” in cars during evening hours. They could not leave town without approval or return before curfew. They could not enter any man’s room or fraternity unless it was an approved event. They could not smoke outside. They could not possess or drink any alcohol. They could not ask for or accept a ride from students or acquaintances.

Per the 1942 Wake Forest Student Handbook none of these rules applied to male students.

They were told when they could go on dates, had to have chaperones for their dates as freshmen and their social privileges could be revoked at any moment. Punishments were referred to as “campuses” or “call downs” where these 18 to 22-year-old women would essentially be grounded to their rooms.

The vast majority of the WGA rules revolved around how to appropriately act around the male students and all discretions were handled by a council of their fellow female students. They were intended to hold each other accountable but forced women and friends to tell on each other. The male students still held all power socially and educationally on campus at this time.

Although Johnson’s rules might be considered controversial today, she left a lasting legacy on the ability of college women at the time to have a say in their own rules. In 1973 she was given the Medallion of Merit and her name is honored by Johnson Residence Hall — the seal of which contains three eyes to represent her “watchful but well-intentioned administration.”

The scandal

On Saturday, May 11, 1946, a student named Madge decided to leave campus to spend the night in Raleigh, N.C. with her sister. (Editor’s note: The Old Gold & Black has agreed to keep Madge’s last name private to respect her privacy, but the records are available to Wake Forest students in ZSR Special Collections.) She had looked for Miss Beulah, the dorm mom from whom she had always gotten permission to leave but could not find her. She left and wound up at a party at the Carolina Hotel in Raleigh but stayed a mere 15 minutes due to only knowing a few people there.

She spent the night with her sister and when she returned to her dorm in the morning, the tension was palpable.

“The atmosphere was a little heavy to say the least,” Madge recounted in her WGA trial. “I asked them what was wrong, and they said everybody had been looking for me, and Miss Johnson was worried.”

The WGA accused her of making her bed to look like she was asleep and not in Raleigh, unscrewing the lightbulbs to make her room look dark, being at a party in a room with alcohol and for not acquiring permission before leaving.

She was called before the council where she had to defend herself, as her other dormmates were forced to give testimonies about her actions and whereabouts, leading up to her departure and after her return to campus.

Madge had not broken a single rule that applied to men, but she was put before the council because she was a woman.

“Others have told you only times we can say anything certain,” a female classmate said to the council. “I have heard from several boys that she could out-drink any boy on the campus.”

And with that, Madge was officially suspended from Wake Forest on May 14, 1946.

Over seventy years later

Madge went on to become an educator, got married and had children, and eventually, grandchildren.

The WGA no longer exists, and we have since had a female student body president and a female president of the university. 57% of the student population is female and all students are held to the same standards of conduct.

Despite the massive improvement of conditions for female students, it remains important to understand the trajectory of women’s equality at Wake Forest in order to appreciate how far we have come. It is worth remembering the legacy of Wake Forest women in order to keep pushing forward toward complete equality.