About halfway through reading Benjamín Labatut’s breakout novel, “When We Cease to Understand the World,” I texted a friend of mine, “I feel like I’m reading cocaine.” The 2021 International Booker Award finalist — which fictionalized the lives of some of the most important and problematic scientific geniuses of the twentieth century — had me instantly hooked. But after slugging my way through the final sections, I was left with a lukewarm feeling. Labatut had captured lightning in a bottle at certain points — certainly the sections on Fritz Haber and Shunichi Mochizuki — but eventually he went too far and completely lost the reins, nearly overshadowing the brilliance of the earlier passages.

In “The MANIAC,” which was released in September of this year, Labatut comes back in full force, completely rid of all of the juvenile mistakes that weighed down his previous work. Instead of focusing on a wide range of individuals, “The MANIAC” centers around one man: John von Neumann — the father of the modern computer and perhaps the closest humanity has ever come to producing a computer of its own. Instead of trying to get inside the mind of von Neumann and write from his perspective, Labatut instead writes from a wide range of perspectives that surrounded him, such as famous mathematicians like Richard Feynman and more intimate companions like his wife and daughter. With this move, Labatut is able to capture two essential things at once — the reverence and awe with which his achievements were received, as well as the devastation that his mathematical obsession wrought on those who truly loved him.

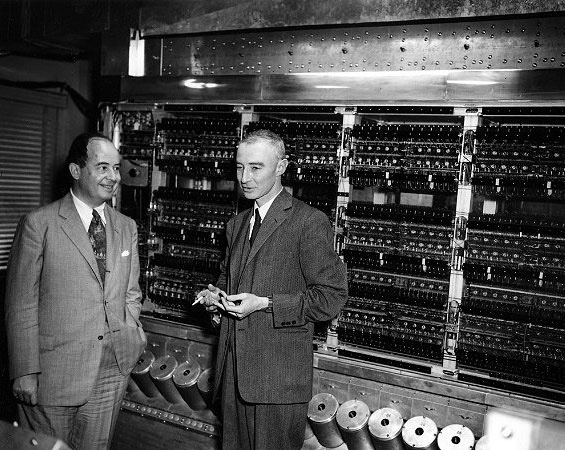

“The MANIAC” paints a picture of von Neumann as a blithe, childish prodigy whose tenacious pursuit of knowledge completely blinded him to the ramifications of his discoveries. From the Manhattan Project to the ENIAC (the first general-purpose electronic computer), von Neumann’s fingerprints are all over the theoretical landscape of the 1940s and ‘50s. He knew so much that when he was on his deathbed, he had to be sequestered by the United States government in order to ensure he did not accidentally leak any secrets or ideas to the general public in his incoherent ramblings. His early contributions to game theory were instrumental in the development of modern economics and the Cold War, and perhaps most importantly, he is one of the founding fathers of artificial intelligence. This was a man so gifted and mathematically superior that at the Institute for Advanced Study, which housed minds like Robert Oppenheimer, Albert Einstein and Kurt Gödel, there was a common saying that “most mathematicians prove what they can, von Neumann proves what he wants.”

But as is the case with most geniuses, his virtuosic mind cost him a great deal in those fields of life that are not governed exclusively by the rules of logic. Labatut conveys with forceful persuasion the unhappiness of those who were closest to him — a tumultuous, turbulent marriage; a daughter who felt spite and resentment for him up until his death; a childhood friend who was always lurking in his shadow. What is more subtle, however, is how Labatut depicts the horror that von Neumann unleashed on the world.

Labatut’s critique of science when reduced to blind, rationalist progress is what makes this book so special. Unlike “When We Cease to Understand the World,” he does not focus his attention on the atrocities like the deployment of the nuclear bomb, but instead on the overwhelming shortcomings of the man who was able to make such developments possible. Von Neumann as depicted by Labatut is a compelling subject because he is not driven by ambition, jealousy, fear or any of those motivators we are accustomed to reading about. Instead, he is portrayed more like an ignorant child, not necessarily callous to everyone around him but tragically in love with the questions and issues of his field. Instead of a human, he becomes a synecdoche for progress itself.

“The MANIAC” does a lot of things, and I will try to name just a few. It contextualizes and explains some of the most important scientific and mathematical discoveries of the twentieth century. It shows how devastating scientific advancements can be — not only for those who are victimized by them but also for those who wield them. It forces you to think about what is fact, what is fiction and what could be either. Most importantly, it is an exasperated plea for a new relationship between the sciences and the humanities. Von Neumann once said, “Cavemen created the gods. I see no reason why we shouldn’t do the same.” In this book, Labatut, looking around at the dizzying pace of progress in the fields of artificial intelligence and computer science, is making a very strong plea for us to take a pause and look around seriously for such reasons.