Early findings suggest that PFAS levels in the blood of residents living in the Cape Fear River Basin may be decreasing, according to a scientific study out of North Carolina State University, but it remains unclear what health impacts residents may face as a result of repeated exposure to toxic chemicals over decades.

Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, more commonly known as PFAS, are chemicals used in many household products. Evidence suggests that exposure to any of the thousands of types of PFAS may increase the risk for a variety of health issues including thyroid disease, low birth weight, increased cholesterol levels, cancer and more, as indicated by the CDC. They line popcorn bags, coat non-stick pans and make rain droplets pool on the outside of waterproof jackets, according to the EPA.

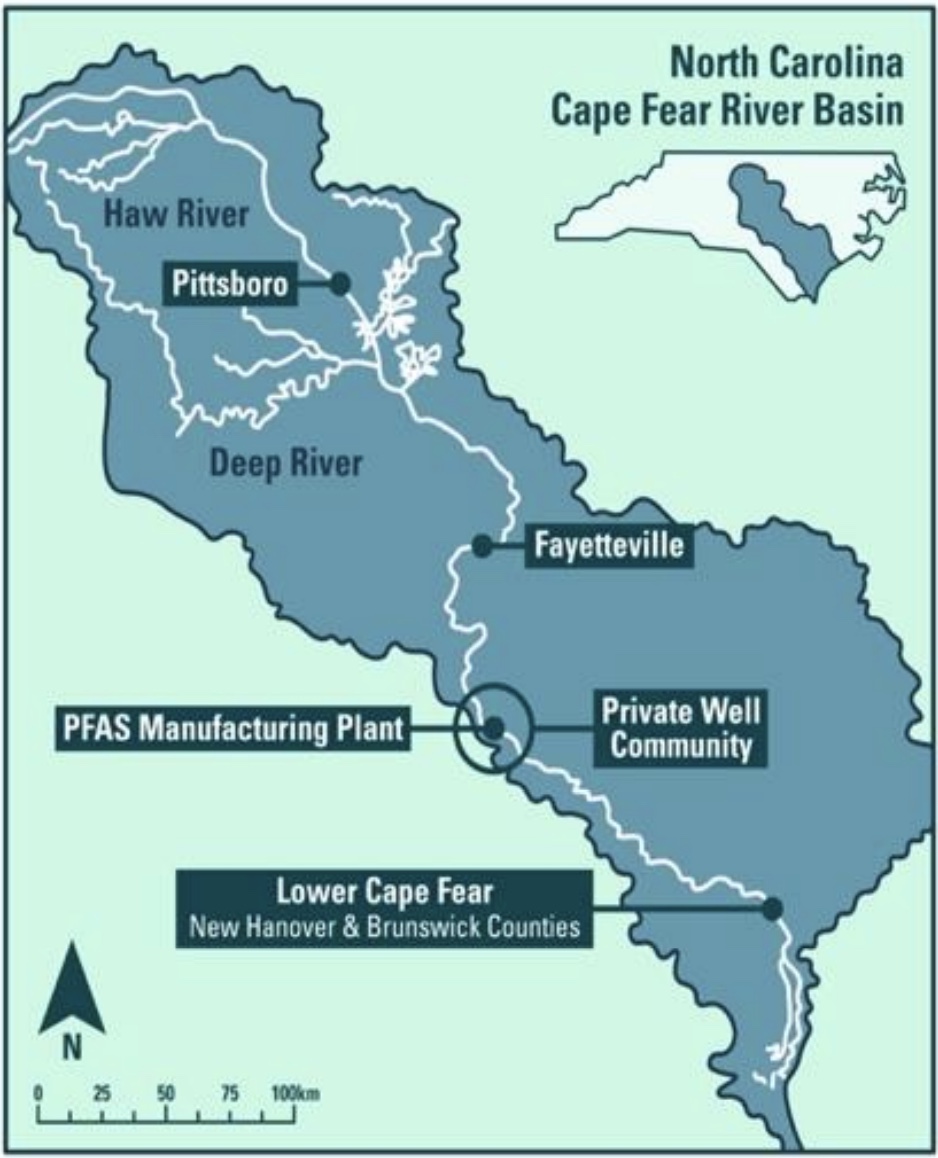

In North Carolina, residents living downstream of Chemours, a DuPont chemical spin-off located along the Cape Fear River, are exposed to PFAS at even higher rates than the average American because they have an additional exposure source: drinking water.

Prior to a 2019 directive from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) that required the company to stop releasing GenX and other PFAS, Chemours released the chemicals into the air at its Bladen County facility for decades, a United Nations report found.

Hanna Bailey is the community engagement coordinator for the GenX Project, which gets its name from the Chemours chemical. The study is led by Dr. Jane Hoppin, an environmental epidemiologist at North Carolina State University, and includes other researchers from North Carolina State University, East Carolina University and Duke University. Bailey’s role is to disseminate key findings from the study to the general public, specifically the communities tested by the study.

“[The GenX Project] started in 2017 because this big report came out that found that the water in Wilmington had PFAS in it,” Bailey said. “Dr Hoppin, along with several other researchers, immediately put in for a grant to start studying it.”

According to Bailey and a webinar hosted by the GenX Project in August 2024, over 1,000 people are enrolled in the study across communities in Pittsboro, Fayetteville, Brunswick and New Hanover counties.

Between 2020 and 2021, the study collected blood samples from 1,020 people in the Cape Fear River Basin. In 2023, around half of those individuals were resampled, and researchers aim to resample the remaining members of the 2020-21 cohort this year.

The study examined the blood levels of 41 common PFAS, including those known to stem from the Chemours plant. Although levels of PFAS in residents are higher than those of the average American, the preliminary results of resampling demonstrate promising results in terms of blood PFAS levels over time.

“Overall, we are finding that PFAS [blood] levels within our participants [are] going down, [and] we’re seeing [this] trend across all three communities,” Bailey said. “That’s not to say every individual is having PFAS levels go down, because there are some people within the study whose PFAS levels have increased since enrolling. We are trying to figure out why that is.”

PFAS levels in most participants have likely decreased as a result of advanced water filtration systems installed at the Pittsboro and Wilmington water filtration plants, as well as two plants in Brunswick County. NCDEQ regulations have also decreased the amount of PFAS released, although prior groundwater contamination has not yet been cleaned up.

The study’s findings shed light on a common misconception about PFAS: that all PFAS are so-called “forever chemicals” that never break down in the body or elsewhere.

Dr. Heather Stapleton is an exposure scientist and environmental chemist at Duke University. She is currently the director of the Superfund Research Center and the Duke Environmental Analysis Library, both of which are part of the Nicholas School of the Environment.

Stapleton emphasized that PFAS differ in their half-lives, or the amount of time they take to break down.

“The term ‘forever chemicals’ was coined by someone talking primarily about what we call proporal alkyl acids, or PFAAs, which are [specific] chemicals like PFOA and PFA,” Stapelton said. “Those PFAS have very long half-lives, particularly in our bodies, they’re in there for years. However, [those are] not the only PFAS, right? There’s actually, depending on which resource [you choose], over 9000 to 15,000 different PFAS out there.”

Stapleton is not directly involved in the GenX Project today, but she researched PFAS in Pittsboro around the same time that Hoppin began her study in Wilmington. Over time, the two researchers combined their datasets to make the study more expansive. Hoppin has continued her work with blood PFAS levels in the Cape Fear River Basin while Stapleton has shifted toward more industry-specific PFAS exposure, like firefighting.

Although total blood PFAS levels are decreasing across the study’s participants, that doesn’t necessarily indicate that health effects from exposure have been eliminated. Not all PFAS last in the body long-term, but those that do are ones scientists know cause health issues.

“The focus on the PFAS that are forever, [the] chemicals that are persistent, is [because] we have sufficient data to suggest that they’re a health problem,” Stapleton said. “Everyone focuses on them because then we can interpret what the data means in terms of whether it’s a high enough level to be a concern or not.”

Despite academic advances in the study of PFAS with long half-lives, Stapleton emphasized that more work is needed to examine the effects of PFAS in the body for shorter periods of time, including GenX.

“There’s a lot of these other PFAs that are out there [that] we’re exposed to,” Stapleton said. “We don’t know as much about them, even if our body’s excreting them. That doesn’t mean they’re not going to be safe. That doesn’t mean they’re safe. They could still have a health effect; we just need more time and more data.”