This is Not About Land

Less than 70 years ago, driving to “Wake Forest” would have taken you to both the home of the Demon Deacons and a city 100 miles east of the current campus. The story of the town of Wake Forest and the university’s transition to Winston-Salem has been continuously reshaped and rediscovered. Yet, it is a story that connects the university to a complicated history. This land, that of Winston-Salem and Wake Forest, N.C., has become a forgotten witness to the tale of the oppressed and privileged alike. This land, divided between two cities, shares a history defined by those who have occupied it. The land’s story deserves to be told through a more truthful lens to ensure that our expressed institutional progress is not in vain. This is a narrative of human experience defined by its relationship to Indigenous communities, to the horrific institution of slavery, to a religious minority seeking a safe haven and to one of the wealthiest families in the North Carolina’s history. So, while this is a story about land, it really isn’t. This is more so a story about these people and how they shaped this community — unearthing the context in which pro humanitate must be understood.

This story begins with a 617-acre plot of land.

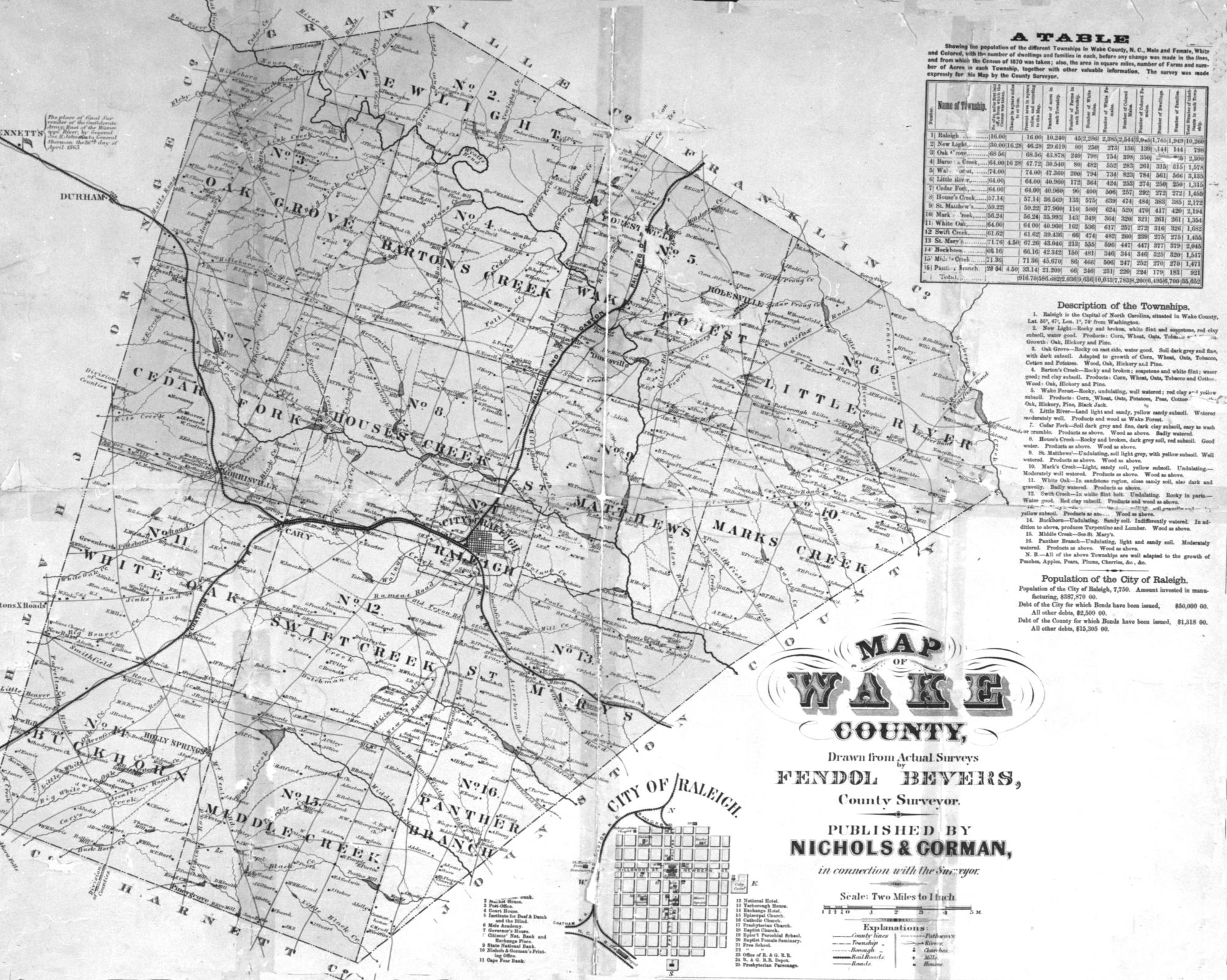

This plot would later become the town of Wake Forest, and it was initially owned by David Battle, who sold it to a man named Calvin Jones for $4,000 in 1821. Jones was born in Massachusetts, moving to North Carolina in 1795 and later marrying a planter-class woman named Temperance. In the antebellum United States, the planter class was a racial and economic caste that indicated inclusion in the Southern white aristocracy for persons who owned at least twenty enslaved persons and several hundred acres of land. From his marriage to Temperance, Jones came into possession of several enslaved persons, and he purchased Wake Forest in hopes of starting a successful plantation.

Within a “fine grove of oaks,” Jones built his farm — cultivating corn, wheat, cotton, hay, vegetables, fruit and brandy. He and his family, as well as the enslaved persons and their families, lived and worked together on this land for 13 years, their living quarters not 100 feet from each other. When Jones attempted to sell the land several times throughout the 1820s, he described the plantation as “well-ordered,” with all the necessary buildings. The main house, he wrote, had a “portico,…[five] rooms with fireplaces, [three] lodging rooms without, and garrets and good cellars, the whole decently furnished and in good repair” as well as outhouses, gardens, barns and blacksmith and carpenter houses. He did not, however, mention the seven slave dwellings in his advertisement, which were blocked from view of the main house by a five-foot-high stretch of corn.

In 2019, Matthew Capps performed the first formal study of the Calvin Jones plantation and the nineteenth-century Wake Forest College campus. While most of the material was readily available, no one bothered to put it together in an analytical study until Capps’ work as a part of the broader Wake Forest Slavery, Race, and Memory Project. According to Capp’s report, Wake Forest students later lived in those slave cabins — walls that once reinforced the bonds of slavery became the backdrop of the path to the economic freedom that a college education offered.

Although Jones attempted to sell the land several times, he was unsuccessful until 1832 when the North Carolina Baptist Convention offered to buy it for $2,000 — half of what he originally paid. Jones and his wife moved with about 20 enslaved persons to Tennessee where Jones had purchased more land, leaving the “Forest of Wake” to other stewardship.

The Wake Forest Manual Labor Institute opened its doors in 1834, providing a religious and agricultural education for just $60. A student’s duties were not just academic because, in those early days, everyone had to lend a hand in the manual labor required to keep the property functioning. However, the students grew weary of such “dirty work,” so the faculty brought more enslaved persons to work on the campus. It is important to note that the university at this point was deeply reliant on the institution of slavery. Though this was not unordinary for the time, as the university was participating in “the Southern culture of slavery,” its commitment to pro humanitate must be read against a past dependence on forced labor.

In 1835, the students founded Wake Forest Baptist Church following a religious revival. According to the Wake Forest Historical Museum, the church’s services were originally segregated, with early records suggesting that “a white minister led services for white congregants in the morning and Black congregants in the afternoon.” About 15 years later, the Black congregants separated and formed their own church with elected Black deacons called the “African Church” or “African Chapel.”

The university did not accept Black students until 1962, but Black people were always present on campus. In fact, Wake Forest was never a completely white space at any point in its history. Black persons were not treated equally in any regard, unable to earn an education at the university but still crucial to the functioning of the university through their work as forced laborers and later as employees. The exclusion of Black persons from academic spaces until 1962 has modern-day implications: fewer Black applicants can be deemed “legacy students” because their ancestors were denied an education at Wake Forest for 128 years, which is roughly double the amount of time since desegregation.

The town of Wake Forest, literally incorporated as the “Town of Wake Forest College” in 1880, grew with the school, which rechartered as Wake Forest College in 1838. “There is no town of Wake Forest without the college,” explains Wake Forest historian Dr. Sarah Soleim. According to Soleim, the existences of the two are intertwined and inseparable. The town developed to cater to the college, as the downtown stores’ primary patrons were students. Outside of the college, the town was predominantly home to scattered farming families and their small estates.

Although the cotton mill was a major employer of the town separate from the college, the Wake Forest economy was largely dependent on business from the school. The town continued to grow alongside the school, reaching a peak population of 3,704 in the early 1950s. The 1946 move from Wake Forest to Winston-Salem was devastating to the town’s economy, especially downtown. While the seminary school opened its doors in Wake Forest in 1951, those students were not actively patronizing the area because their primary residences were not on campus. They were older, they had families and they worshiped and led services at home churches outside the city lines of Wake Forest. In the years following the school’s move, the town of Wake Forest annexed many smaller communities around it, including the mill town, which increased the net tax revenue it could receive and ultimately kept it afloat. Even with the annexations and the addition of the seminary, the town’s population dipped significantly, not reaching its peak population again until the 1980s.

For a campus that is now so beloved, it’s a little bit ironic that alumni of the original location needed convincing of the move to Winston-Salem. Pamphlets were sent out to persuade them to support the transition through monetary donations, suggesting they were not immediately on board. They were curious about what Winston-Salem was like, what the new campus would be like and who this Reynolds family was who had so generously offered land for scholarship.

Currently, few people know about the depth of the connection between the town of Wake Forest and Wake Forest University — how the town would not exist without the university that once resided within its borders. It seems like even fewer students have ever been to the original campus. Prospective students hear about it when they first tour, but rarely ever again. To most, Wake Forest University is the new campus in Winston-Salem. It’s where so many people grew up coming to football games, where the last 70 classes graduated, and where a lot of alumni consider “home.” However, the Wake Forest community must recognize that the university is also all of the original buildings in Wake Forest, N.C. — it is all of the people who worked and taught and studied and lived there. It is the town that grew to support it and stayed when it left.

While the school’s history is split between two distinct locations, its past is not so bifurcated. Its influence remained beyond the day it left the town of Wake Forest, and it appeared in Winston-Salem long before classes actually started.

Despite their fame and influence in the area, Winston-Salem’s history did not begin with the Reynolds family. In fact, evidence of Indigenous presence in Forsyth County dates back at least ten thousand years. The first archaeologist in Forsyth Country was Moravian Reverend Doug Rights, who was the founding member of the Archaeological Society of North Carolina in 1933 and discovered thousands of Native artifacts in the area. Andrew Gurstelle, professor and academic director of the Lam Museum of Anthropology, explained in an interview how in the 1980s, Wake Forest was given 15,000 Native artifacts that Rights collected, which kickstarted the school’s archaeological work and understanding of the history of its land. A portion of that collection is on permanent display at the museum. This land, he explained, is important to several Native groups, namely the Catawba Nation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Coharie, the Tutelo, the Sappony and the Lumbee. The museum has worked to maintain connection and conversation with those groups through many pathways.

While several departments and disciplines at Wake Forest have made an effort to incorporate Indigenous Studies into the course curriculum (for example in English, Religion, Linguistics, History and Archaeology) over the years, currently only one course is devoted specifically to Native history: Lisa Blee’s “Modern Native American History” course. While numerous courses integrate elements of Indigenous studies, students may not develop a deep understanding of the historical and current issues facing Indigenous people and their communities during their time at Wake Forest. The university released a land acknowledgment five years ago, on Nov. 4, 2019, claiming Wake Forest “continues to be a place of learning and engagement for Indigenous students, faculty and staff regionally, nationally and globally.” Acknowledgment is surely much better than erasure. However, there is still much to be done for this statement to reflect a truly continuous effort. The prioritization of connection with local native communities, the hiring of staff for that purpose — and Native staff members in general — within specific departments, and increasing momentum within the student body to push for more courses on Native history will bring this campus closer to living up to its promises.

Gurstelle went on to describe how the European history of Forsyth County begins with the Moravians, a religious minority group in Pennsylvania who sought economic security to support their faith community. After purchasing land from the governor of North Carolina, Lord Granville, they came to Forsyth County and settled in Bethabara. When the Moravians arrived at Forsyth, it was empty. But just a few years earlier, in the late 1600s, German explorer John Lederer came through the area, and he described the Saura (sometimes spelled Cheraw), a native group who lived in the area, in his catalog of adventures aptly named “The Discoveries of John Lederer.” However, the Saura decided to move south, joining forces with the Catawba nation after European disease and native warfare made the land in Forsyth County inhospitable. Just 60 years before the Moravians arrived, the Saura were working and living in Bethabara — this European story was separated from the Indigenous one by time only.

When the Moravians first arrived, they lived out of a pre-existing barn. Although this structure signaled they were not the first Europeans in the area, they were, indeed, the first major European settlement group. Lord Granville’s only claim to the land he sold the Moravians was that it was within the drawn borders of North Carolina. Other colonists had not marked the area with anything of note, and it had not been bought from anyone as it was largely unoccupied. It was just there.

This stretch of land was considered the Western colonial frontier. The Moravians wrote a daily entry of the town occurrences, which cataloged their interactions with Cherokee, who moved in and out of the area frequently. Gurstelle explained, “Quickly one of their most lucrative trades [was] with Indigenous people.” Therefore, while the Moravians and Cherokee weren’t next-door neighbors, they were never truly separate. The Moravian’s success as a settlement was largely thanks to their close working proximity to these Indigenous persons. Gurstelle, describing the story of the settlement of Forsyth and the broader colonial project, explained, “This was not a story of replacement.” Instead, it is a story of overlapping lives, which deserves recognition when discussing past and ongoing relationships and interactions.

The Moravians continued to build their settlement in Bethabara. Some moved to what would later become Bethania in 1759, and they broke ground on their permanent settlement in Salem in 1766. When R.J. Reynolds arrived in Winston-Salem in 1874 to establish his tobacco factory, many farmers in the area were already cultivating the plant as a cash crop. Thus, there was already a rich tradition of tobacco to draw on and use as a resource when he came. Reynolds married Katherine Smith, his first cousin once removed, in 1905.

Katherine was a huge proponent of the expansion of Reynolds’ property. According to the Reynolds Foundation, she made 27 land acquisitions over the next 13 years, which became the Reynolda estate. The acquisition of the Reynolds’ land was not one collective purchase but several purchases from small landholders and churches in Forsyth County. The land was mapped out through sketches on bits of paper and attached to the deeds, marking the rough size of the plot and the streets or notable landmarks that surrounded it. The Reynolds farm was self-sufficient, eventually spanning 1,003 acres, growing many types of vegetables and cultivating a remarkable garden and greenhouse. Those on the estate also raised hens, cows, hogs, and horses. In 1917, Reynolda was described as “a happy community” of “about twenty resident families.”

The land that the university now occupies was largely part of the orchard section of the Reynolds farm. After the tragic and sudden passing of Z. Smith Reynolds in 1932, the Smith Reynolds Foundation was established to support “educational and charitable organizations throughout North Carolina.” The estate’s land at that point was divided amongst the Reynolds heirs, and Mary Babcock Reynolds and her husband purchased the land from her siblings so the estate was cohesively under their authority. The couple wanted to expand the legacy of the Reynolds family and their foundations. So, in 1946, they wrote to the trustees of Wake Forest College and made them an offer they couldn’t refuse: a proposed relocation to 300 acres of their estate as well as $350,000 per year in perpetuity.

It was surprising and generous — so much so that there was a significant question over if the proposed contract could legally be upheld. How could this agreement be enforced or even promised forever? The contract went to the State Supreme Court for a declaratory judgment. The statement from Reynolds Foundation v. Trustees of Wake Forest decided that it didn’t matter where the university was located. They could still educate and pursue their mission Pro Cristo et Humanitate in Forsyth County. The State Supreme Court wrote, “We would not deny to this great institution and to those whose faith and good works have made it possible, this vista of a new dawn and this vision of a new hope.”

The contract was deemed legal, so efforts to transition the campus to Winston-Salem began. With this gift from the Reynolds Foundation, the school ranked in the top 10% of all American colleges in regard to endowment. Wake Forest Medical School announced its move to Winston-Salem in 1939, so the transition was not unprecedented, but it still rocked the community of Wake Forest, N.C.

On October 15, 1951, President Harry Truman broke ground on this “new dawn” for the college. The university didn’t officially transition until the summer of 1956 when construction was finished. Since then, Winston-Salem has been its home, and the connection to Wake Forest, N.C. has faded in all but name.

The history of Wake Forest and the land that it now occupies is complicated. It is a story of agriculture and ministry, enslavement and wealth and two towns over a hundred miles apart. It is a story of land that has been walked by people for thousands of years. This place, while it feels permanent and rich with tradition, is incredibly new — in both the life of the college and in the span of human presence in Forsyth Country. Yet, how often do visitors think of who laid the bricks they stroll across, of who walked the earth beneath those bricks before they were laid? Do students ever think of the alumni who came before them? How often is Wake Forest, N.C., mentioned outside of a quick fun fact on a college tour?

Only in the last few years has this history been publicly unpacked and examined. But, if the origin of the school has been so easily forgotten, how much more is the legacy of forced labor, religious minorities and the help of Indigenous persons swept under the rug to promote a more appealing narrative of academic excellence and philanthropy? While Wake Forest has failed to live up to its motto in the past, a new commitment to exploring and doing justice to its history will bring the school closer to living out and understanding what it means to be “for humanity.”