Sacoby Wilson, a professor in the Department of Global, Environmental and Occupational Health at the University of Maryland College Park, is driven by environmental issues that shaped his childhood. Growing up in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Wilson lived in a neighborhood surrounded by a major highway, a sewage treatment plant and a landfill — the latter two were less than a mile from his home. Some of his classmates lived right next to the landfill, a reality Wilson didn’t fully comprehend until later in life. His father worked as a pipe-fitter at the nearby Grand Gulf Nuclear Station, where he was exposed to asbestos.

These early experiences ignited his passion for biology, toxicology and environmental science. While at Alabama A&M University, earning his bachelor’s degree, Wilson joined the Minority Biomedical Research Support program through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and became an Environmental Protection Agency Minority Academic Institutions fellow during his freshman year. His work in these programs helped set him on a path to becoming a leading voice in environmental health.

The Environmental Careers Organization (ECO) program within the EPA fellowship, which focused on diversifying in the environmental space, introduced Wilson to Robert Bullard and Benjamin Chavis. Meeting them sealed Wilson’s future in environmental justice. After this, he pursued his master’s and PhD in environmental health sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He admits his attendance was less to do with the university being a top ten institution in his field and more to do with Michael Jordan.

With the birthplace of the environmental justice movement in Warren County, N.C., Wilson’s time in Chapel Hill allowed him to grow up amid community leaders and founders of the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network. His experience engaging with communities on the front lines of the environmental justice movement pushed him toward a postdoc at the University of Michigan. There, he was part of the Robert Wood Johnson Health and Society Scholars Program, where he received mentoring in social epidemiology.

He entered the academic track as an assistant research professor at the University of South Carolina and has been at Maryland since 2011. The Old Gold & Black sat down with Wilson in advance of his lecture at Wake Forest.

Shaila Prasad: What kind of environmental justice work were you involved in during your time at Chapel Hill?

A big chunk of my graduate work was working on industrial hog farming with community-based organizations who were fighting against the industry in North Carolina. My work was using the community-based participant research framework to engage with communities and residents impacted by industrial hog farming — it’s what my dissertation was focused on.

[My PhD classmates and I] also did a lot of work to look at the issues around the built environment, looking at sewer and water infrastructure in historically black neighborhoods. Because of segregation, rail lines and racism, these neighborhoods were not connected to publicly regulated soil and water infrastructure. If they were connected to the public lines, they were connected to lines that were not up to code. It’s what we call the lack of basic amenities.

Prasad: What impact would you say universities and academic institutions could have in advancing environmental justice, if any?

I can say they haven’t done the best job. In many cases, it’s not the full university that’s part of that particular community. It’s one faculty member, it may be one student group, or it may be one class. Universities, when it comes to our mission of serving people, have failed. You don’t have that many programs in the country where students are being trained in environmental justice.

The first time there was real funding for environmental justice was the Biden-Harris administration. As we know with the current administration, they’re trying to claw back and erase those programs. But you can’t erase the legacy of the environmental justice movement at the federal level. So you see, many universities have a mission to serve people, but they have, to be honest, failed at serving folks who’ve been impacted. I’m not saying there aren’t some faculty members putting in the work. But while they may be doing the work, they’re not being fully supported by their schools or universities.

Prasad: How do you deal with the emotional reactions you have to the realities you come across during your work?

As an advocate, I think it’s important to do work that’s going to be beneficial to communities that have been impacted. That’s the widest part of my life’s mission. There is an impact emotionally from a negative perspective, but also from a positive perspective, because as a scientist, I think it’s important to make sure you have an impact. I get my emotional nutrition from working with communities. Because I’m working with them, uplifting their knowledge systems, uplifting the experiences, valuing the contextual expertise and knowledge. I get my emotional energy from doing that work. It’s important for me because that’s part of who I am. That’s where I come from. So yes, there’s some negative emotional impacts. But I think for me as a scholar, researcher and advocate, that’s where I’ve had the most emotional benefits, emotional gains in this space — working directly with communities.

Prasad: What are essential things to remember when stepping into such communities?

For me, it’s been really important to do empowerment science and to do liberation science with communities. Through these community partnerships, we make sure we’re putting communities first, and that the voices are driving the science. That’s one of the things about environmental justice, you want the community to speak with their voice, self-determination. So from the research perspective, we will make sure that they’re engaging in the work, they’re driving the research we do and we’re solving their problems. It’s just not an academic exercise. We’re doing science that can change lives.

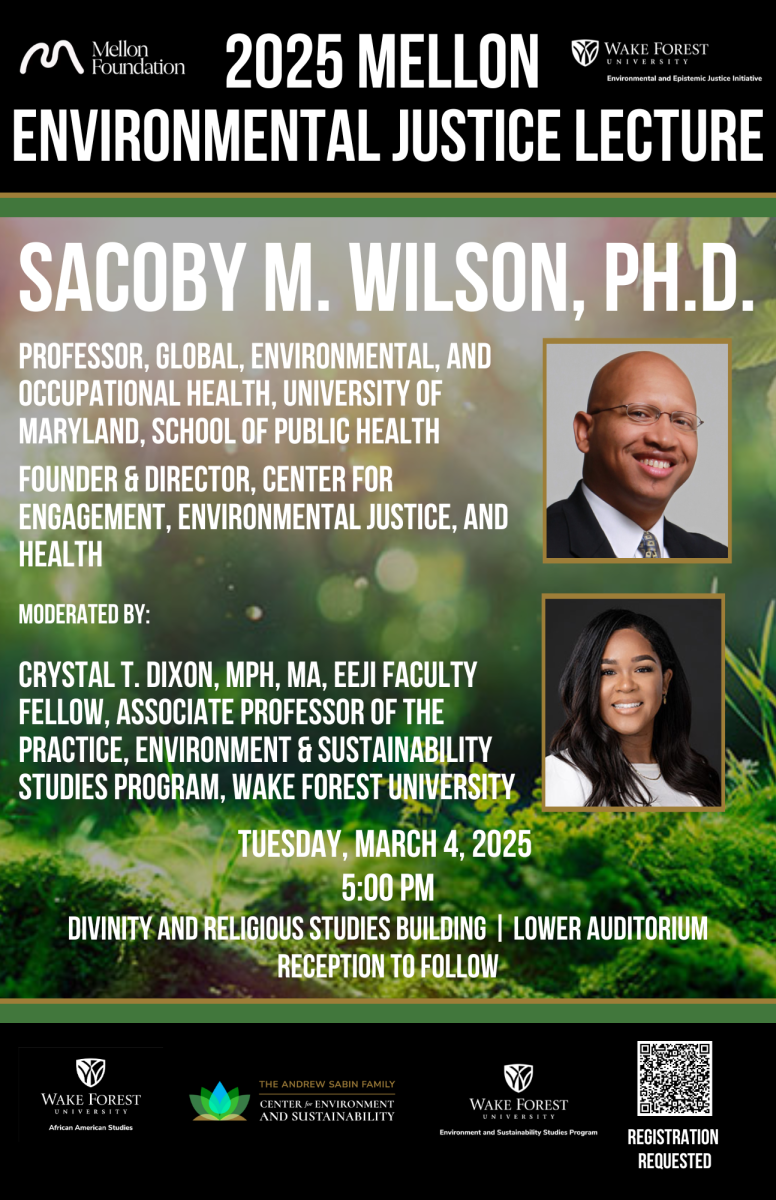

Dr. Wilson will be speaking at the Mellon Environmental Justice Lecture, on Mar. 4 at 5 p.m. in the Divinity and Religious Studies Building. You can register here.