Students living on South Campus likely recognize the blue and yellow lighthouse crest that belongs to South Residence Hall. This emblem, however, will soon be replaced with a new crest that depicts a heart and a half-open door, marking the building’s forthcoming name change.

The soon-to-be Hopkins Residence Hall will honor two trailblazing individuals, Larry D. Hopkins and Beth N. Hopkins, who have left indelible impacts on the Wake Forest and Winston-Salem communities.

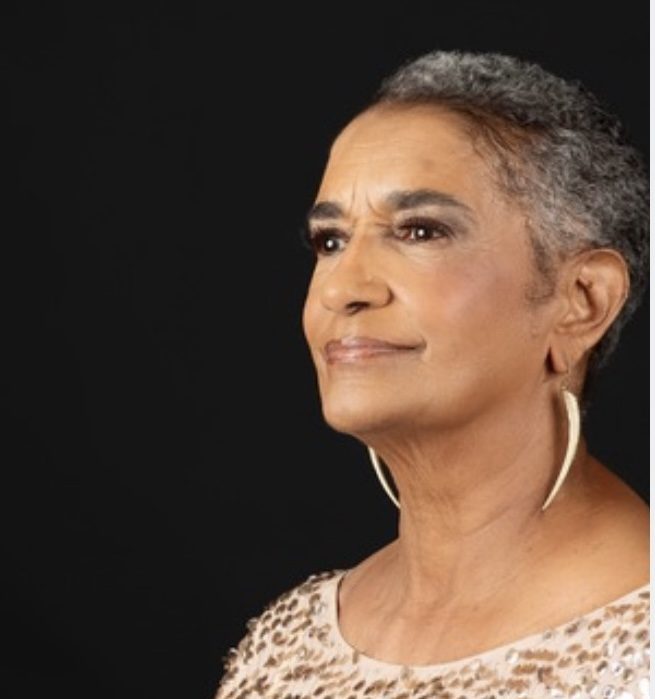

Beth Hopkins: achievement in the face of adversity

Beth Hopkins (‘73) has personified Wake Forest’s pro humanitate motto for over fifty years. Throughout the decades, she has served as a campus leader during some of Wake Forest’s most transformational moments.

One of the first Black women to attend the university, Beth Hopkins first enrolled at Wake Forest in 1969. At the time, fewer than 30 Black students called Wake Forest home, and the university community was often a hostile environment. Professors explicitly doubted Black students’ academic capabilities, sometimes voicing their skepticism to students directly.

Hopkins’ election as Homecoming Queen in 1972, though a mark of the student body’s support for integration, was seemingly glossed over by campus institutions such as the Old Gold & Black, which declined to write a story about her achievement. It’s no surprise that at the time, Beth Hopkins had a less-than-positive view of her days at the school.

“When I graduated from Wake Forest in spring 1973, I vowed I would never return to campus,” she wrote in a 2019 article for Wake Forest Magazine.

For many years, her vow remained true. Hopkins earned her J.D. from the College of William and Mary in 1977 and began her legal career as a federal prosecutor and civil rights attorney in Virginia, where she eventually served as both an assistant U.S. attorney and assistant attorney general.

Hopkins returned to Wake Forest in the 1980s as a law school faculty member and undergraduate professor for a course on race and the courts. She later served as the inaugural director of the Smith Anderson Center for Community Outreach at Wake Forest Law, where she transformed the law school’s Pro Bono Project and the Public Interest Law Organization for six years.

Through her leadership, she forged relationships with private attorneys, local law firms and the local bar association to provide citizens across North Carolina with the opportunity to receive legal counseling from Wake Forest Law students. Over fifteen pro bono projects flourished under Hopkins’ leadership and garnered numerous awards from the American Bar Association and North Carolina Bar Association.

In a 2023 feature video honoring Hopkins’ contributions to the community, Randolph Childress, a friend and mentee of Hopkins’, testified to the energy and determination Beth contributed to Wake Forest. He explained that she has often served as an informal mentor to students and other community members, reflecting the symbiotic relationship she has cultivated with the university.

“She was a person who invested quite a bit in our students and the life skills and character that was a standard for us all,” Childress said. “She was almost like a mom away from home for a lot of us.”

Beth Hopkins reflected on her time at Wake Forest with gratitude, saying that despite the struggles she faced, she would do it all again if given the opportunity. She said she was particularly thankful for the other Black students who walked with her on campus and the intimate community they formed.

“We were a fiery band of students shaping history without an intention to do so,” she said in a 2020 discussion panel honoring five of the first Black women to integrate Wake Forest’s residence halls. “We pulled on the strength of one another, and we had great leaders in our group.”

One of those leaders was fellow student Larry Hopkins. Beth and Larry first met on the steps of Wait Chapel in 1970, shortly after his recruitment to Wake Forest’s football team. Over the following three years, Beth Hopkins would become familiar with the humble yet commanding leader who was her future husband.

Larry Hopkins: a star on and off the field

A dually-gifted student and athlete, Larry Hopkins’s college career was filled with achievement. In the classroom, Larry was a dedicated scholar of the natural sciences and earned a spot on the dean’s list every year he attended Wake Forest. He was the first Black student to graduate from Wake Forest with a degree in chemistry.

Peers recognized Larry Hopkins’s calm yet commanding presence that allowed him to settle conflicts, find consensus and create constructive spaces for conversation throughout the university. Wake Forest recognized his contributions to the community with the Medallion of Merit Award in 2020, the highest honor awarded by the university, given to its most impactful leaders.

“There were times [in college] when we had Afro-American Society meetings, and we would be in an uproar about something,” Beth Hopkins said in a 2020 video honoring her husband with the award. “Then he would speak and everyone would stop and listen.”

Larry Hopkins, known as ‘Hoppy’ to his fans, was also one of the greatest running backs in Wake Forest history. During his two-season run on the football team, he achieved a remarkable 1,228 rushing yards in the 1971 season — a record that still stands today. Larry Hopkins also scored the winning touchdown against the University of North Carolina in 1970, which led the team to its first football win in the ACC championship. In 1989, he was inducted into the Wake Forest Sports Hall of Fame.

A historic academic and athletic tenure at Wake Forest, however, was not the capstone of Larry Hopkins’ accomplishments. After graduation, he attended medical school at the Bowman Gray School of Medicine. He completed his residency training at the Medical College of Virginia, before joining the United States Air Force, where he attained the rank of Major in the Medical Corps.

In 1983, he returned to Winston-Salem to begin a decades-long career as an obstetrician and gynecologist. His vocation exemplified his dedication to community service. As a co-director of the Women’s Health Center, he played a direct role in improving prenatal care for expecting mothers and decreasing the infant mortality rate in Winston-Salem. Larry Hopkins also served on the Women’s Health Center Advisory Board and the Women’s Wellness Center’s Health Advisory Council.

“I realized that I could contribute so much to, not just the women, but to all of society really,” Larry Hopkins said in a 2020 interview. “Whatever I could do to help others makes life worth living.”

Sentiments from Larry Hopkins about his work were few and far between. According to those who knew him well, he rarely talked about himself; when he did, he did so with an infectious smile and a quiet gravitas. He maintained his reputation as a humble and authentic leader until his passing in November 2020.

“My one regret is that [Larry] is not here to share this tribute with me,” Beth Hopkins said in a written statement to the Old Gold & Black. “He was a man of integrity, a stellar student, an accomplished football player, a compassionate physician and a treasured partner to have in my life for fifty years.”

Larry and Beth Hopkins both applied their excellence to give back to their communities, including Wake Forest. Larry Hopkins completed seven terms on the Wake Forest Board of Trustees alongside Beth Hopkins, who is still a Life Trustee.

“I think they were the perfect pair for working on opportunity access, equity, inclusion and justice,” said José Villalba, vice president for diversity and inclusion at Wake Forest, when announcing the resident hall name change. “Instilling in people you have to work together, you have to find a way to… hold hands and say ‘How can we be better for ourselves, but then for our community as a whole?’”

The Hopkins family is a reminder that Wake Forest is a people-driven institution; it necessitates that the very same individuals who seek to gain from the university be trailblazers and bridge-builders in the community’s future.

“I always believed there’s an open door somewhere,” Beth Hopkins said in a video played at the Feb. 20 Founder’s Day celebration. “All you have to do is tug on the knob a little bit.”

Correction, Mar. 28: A previous version of this article online and in print incorrectly stated that Larry Hopkins completed his medical degree at the Medical College of Virginia. The Old Gold and Black confirmed he completed his degree at the Bowman Gray School of Medicine and his residency at the Medical College of Virginia.