The Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) Best Choice Learning Center is a beacon in the Winston-Salem community. Local youth gather many nights a week to eat a hot meal, get help with homework and connect with a caring adult. However, every other Tuesday evening at the center looks different.

Wake Forest School of Law students, local youth and community legal advocates participate in “Teen Court,” an alternative criminal justice system for first-time juvenile offenders in Forsyth County. The program is the result of a partnership between the YWCA and the Pro Bono Project at the Wake Forest School of Law.

Executive Director of the Pro Bono Project Mary Catherine Baker said that Teen Court works to fill the gap between Legal Aid, a non-profit organization that offers free legal services to residents of North Carolina, and private practices.

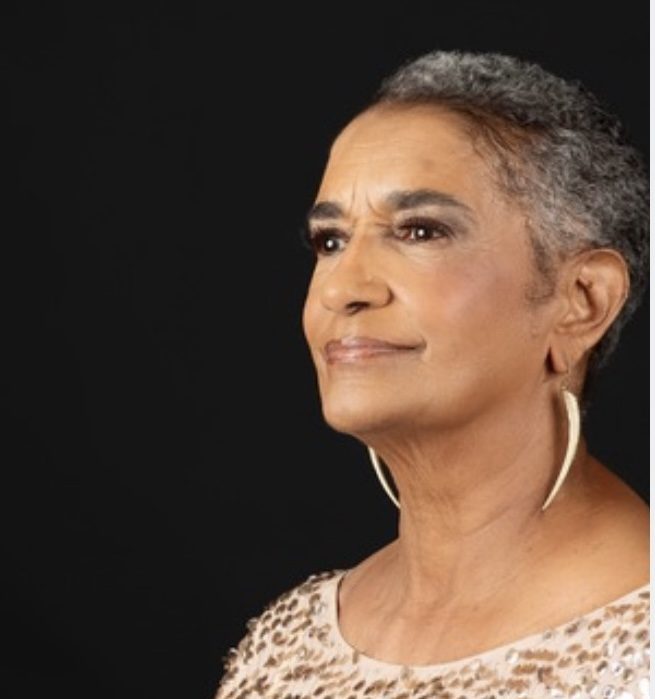

As a deterrence and diversion program, Teen Court puts juveniles in front of a sitting judge in the environment of a real courtroom. The YWCA receives student referrals from local middle and high schools for situations in which the student’s actions constitute a chargeable offense that cannot be handled internally. Teen Court begins with an initial intake interview with a YWCA staff member, often Vice President of Youth Services Danielle Johnson.

“I really try to express to students and parents when they come in for intake that this is a judgment-free zone,” Johnson said. “It is a place where they can feel safe to be open and honest.”

The charged juvenile appears at the Best Choice Learning Center on their assigned court date and tells their side of the story to the defense counsel. Prosecutors ask the juvenile a series of questions about the incident in the courtroom in front of a jury and audience. The juvenile then receives a sentence, which may include community service hours, an apology letter, life skills classes at the YWCA, or any combination of these actions. The defense counsel and prosecution teams are composed of both Wake Forest School of Law students and youth volunteers in the community who provide peer-to-peer mentorship.

“The Teen Court process is structured as a trial. [However], it is more of a sentence hearing because the facts are not in dispute,” said Peyton Mitchell, law student and director of Teen Court. “Admission of guilt [from the teen] is one of the requirements to participate in Teen Court.”

Teen Court can be distinguished from the traditional juvenile justice system because juveniles do not receive a criminal record from the incident. This ensures they have a fair opportunity in their future endeavors, such as applying to college or jobs, without carrying the stigma of a record.

“When Teen Court first started, the YWCA wanted first-time juvenile offenders to have a second chance at getting things right,” Johnson said.

Mitchell said that children should not be labeled as criminals after their first encounter with the justice system. She believes that children are fundamentally different from adults and should be judged accordingly.

“There are cases where we can all agree that this kid is not on the road to a life of crime but is more so a victim of their circumstances,” Mitchell said. “Our Wake [law school] attorneys do a great job of recognizing this and tailoring the prosecutorial style to be more constructive, as opposed to grilling the youth.”

The most common Teen Court charges are substance abuse, disorderly conduct and harassment or assault. However, understanding these charges in terms of juveniles holds different implications than in the adult criminal justice system. Substance abuse does not typically refer to illicit substances but the use of electronic cigarettes or “vapes.” Assault charges in Teen Court often refer to bullying and ongoing conflicts that culminate in brief acts of physical violence.

“A lot of kids who get put on trial in Teen Court are the victims of bullying in school,” Mitchell said. “Sometimes they are literally backed into a corner.”

Johnson reiterated that bullying is a prevalent indicator of juvenile crime. She spoke about a memorable Teen Court story involving a victim of bullying.

“We had one juvenile who was really struggling with being bullied at school and kept it in for a while,” Johnson said. “But it got to the point where she couldn’t take it anymore and when she got to that boiling point, her first reaction was to retaliate physically.”

The juvenile was referred to Teen Court and went through the intake process, relatively unimpacted by the program. However, when immersed in the courtroom as prosecutors started asking their questions, she began crying on the stand. She recognized her behavior was wrong and showed remorse for her actions, according to Johnson.

“She was very receptive to completing her sentence and wrote this wonderful essay about what to do if you are being bullied,” Johnson said. “She came back several times to read her essay in front of our younger students at Best Choice, and it was special for me to see that child rise up and take control of her life.”

She continued: “That was a moment where we could say… my god, this child is special and our program really works.”

Teen Court is a holistic program that considers who the teen is, beyond the charge they are facing. In Forsyth County, children with diverse needs and circumstances find themselves in the criminal justice system. Many Teen Court participants face challenges at home that manifest in inappropriate behavior at school.

“If a teen is struggling at home, a lot of those issues follow them to school,” Johnson said. “How can I be a productive student at school when I have to worry about my stomach growling because I am hungry, or I don’t know where my parents are?”

It is Johnson’s goal to help create a system that sees children as more than their mistakes and provides them with the opportunity for redemption.

“We are here to provide people with services to help them have a second chance at life… to be better, to do better. That’s who we are,” Johnson said. “Teen Court is just another way to reach those children who are struggling.”