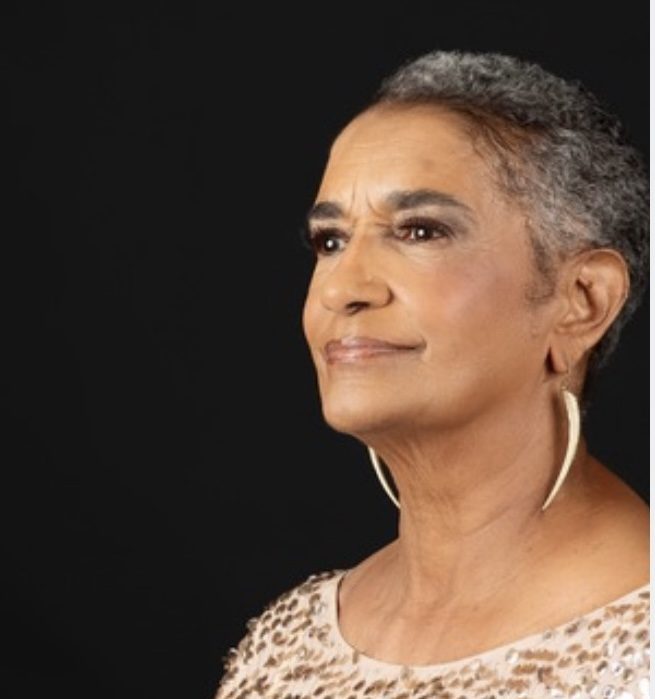

When Camille Russel Love enrolled at Wake Forest University fifty-four years ago, she never foresaw how her future would unfold. From making history as one of the first Black female students at Wake Forest to a storied career ranging from business to the arts to public service, Love has left a trail of accomplishment in her wake.

In her endeavors, Love has woven together two distinct dynamics: she is disciplined, precise and analytical — yet also joyful, free-spirited and unapologetically daring. These traits stand strong in their own right, yet together, they form the foundation of Love’s outlook on life.

The early years

Raised in Winston-Salem, N.C., Love grew up surrounded by a spirit of ambition and service. She found a role model in her father, entrepreneur, teacher, local politician, and social activist Carl H. Russel Sr., a Renaissance man dedicated to many causes. Russel taught his daughter the importance of working hard to give back to one’s community.

“Let the work I’ve done speak for me,” Russel would often say. “Let what I have done be my legacy.”

Love took her father’s message to heart. She displayed academic promise from a young age and broke through the constraints of segregated schooling to take AP Chemistry at the then all-white R. J. Reynolds High School. Outscoring her classmates on each exam, Love quickly demonstrated to her peers and teachers that Black students could compete with their white counterparts. Love succeeded in all her classes, but her most impressive performances were in the hard sciences.

“I learned that I was just as smart as [the other students], especially in things that were black and white,” she said. “The numbers computed, or they didn’t.”

Life as a Demon Deacon

Love enrolled at Wake Forest University in 1970, with financial support from Anne Reynolds Forsyth and Frank Forsyth, local philanthropists and advocates for racial equality whom her father knew well. Though Love faced challenges in college, she cherished her time at Wake Forest because of the institution’s vast opportunities for learning.

Love viewed her time at Wake Forest as a job. Not only did she aim to gain an education, but she also wanted to prove to the academic community that Black students could compete and contribute to the university. This “labor of love,” echoing her father’s sentiment that all work is good work, motivated her stellar academic performance.

Love’s close relationship with then-president James R. Scales often thrust her into a position of advocacy for other Black students. When a professor unfairly graded the writing assignments of Black students, Love collected proof and presented it to President Scales. When two Black football players were accused of cheating, she argued in front of the academic discipline committee to prove their innocence.

Discipline, analytics, and the courage to change

Love’s analytical skills and academic diligence made her a prime contender for a law career. She attended the Duke University School of Law after graduating from Wake Forest. At Duke, however, Love did not find the satisfaction she sought, and she considered leaving multiple times during her first year. When a truck rolled through her apartment a few months after she arrived at Duke, Love considered it a sign — it was time to change course.

After leaving Duke, Love worked multiple jobs in the corporate world: first at Southern Bell, then at IBM, where she stayed for fifteen years as the first Black woman in the South to work as a manager of large system computers.

Love often sold computers to leaders in the insurance and utilities industries who hesitated to take industry advice from a Black woman. From those experiences, she learned that the key to confidence lies in remembering one’s authority.

“You just have to not give a damn about other people’s opinions,” Love said. “They are not walking in your shoes. They did not reach where you are by the same path. So how dare they judge you?”

An entrepreneur in the arts

Although Love enjoyed applying her analytical skills within her role, one of her favorite parts of her career at IBM was the opportunity to travel frequently. She enjoyed exploring different cultures in each city she visited and was especially intrigued to learn more about art.

Love took a leave of absence from IBM in 1987 to work as a loaned executive for the newly-minted National Blacks Arts Festival in Atlanta. Her time at the festival filled the gaps left by her education at Wake Forest, which wouldn’t launch its African American studies program for another 34 years.

When IBM announced its first downsizing in 1988, she sprung at the opportunity to take an optional severance package and permanently change course to pursue a career as an art entrepreneur.

“I don’t fear change or the unknown because [life] has to be an exciting adventure,” Love said. “You need to be flexible and willing to take chances. If you’re committed to it, something’s going to work out.”

Love applied the marketing expertise she had developed at IBM to publish several successful lines of fine art prints. Demand for her business grew consistently, and Love raced to respond by expanding into printing original artworks and eventually opening a gallery of her own.

Bringing Expertise to Public Service

After Love’s gallery became a commercial success, the then-mayor of Atlanta asked Love to direct the Office of Cultural Affairs in 1998. Excited by the opportunity to democratize access to the arts in Atlanta, she decided to accept the role. To counteract perceptions of elitism, Love collaborated with major Atlanta arts institutions to diversify their boards, programming and audiences.

Love’s career in the arts was a perfect synthesis of the two halves of her personality — the precise and the creative, the diligent and the free. Every project with the city required strict administration of budgets, deadlines and attention to stakeholders. Yet, the office as a whole relied on a spirited love of local culture and an understanding of artists’ needs. Love met both of these needs.

While orchestrating local projects, Love worked to instill values of responsibility and diligence in her team members. She told her employees her opinion that no work can be compensated fairly, so a person without passion for their job will always feel unsatisfied.

“I have this firm belief that the work that you do has to be part of your pay,” Love told her staff. “You have to believe that. And if you don’t believe that, you’re in the wrong job, and you should leave now.”

One product of Love’s leadership was the Cultural Experience Project, which introduced Atlanta Public School students to the arts. The organization works with Atlanta arts organizations to provide a free art field trip for every child in the Atlanta Public School System. Over the past 15 years, the Cultural Experience Project has reached over 52,000 students.

Looking to the Future

Love announced her retirement in 2024, after more than two decades of service to the city, but was recruited a mere two months later to serve as senior advisor to the mayor. She is currently directing a series of cultural projects to prepare Atlanta to be one of the host cities for the FIFA World Cup 2026. Love is overseeing work to transform “eyesores into artwork” along the routes to reach the Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

While a much-deserved retirement is surely on the horizon, Love is keeping busy in her job for the time being. When she reflects on her past and present, she explains that she loves being a free spirit who is not influenced by others’ opinions. Love does not hold onto regrets and sees the key to a content life in knowing the power of self-determination.

“I have decided to be a happy person, and to be happy, you have to just be unapologetically who you are,” Love says. “Control is definitely in my hands and nobody else’s.”