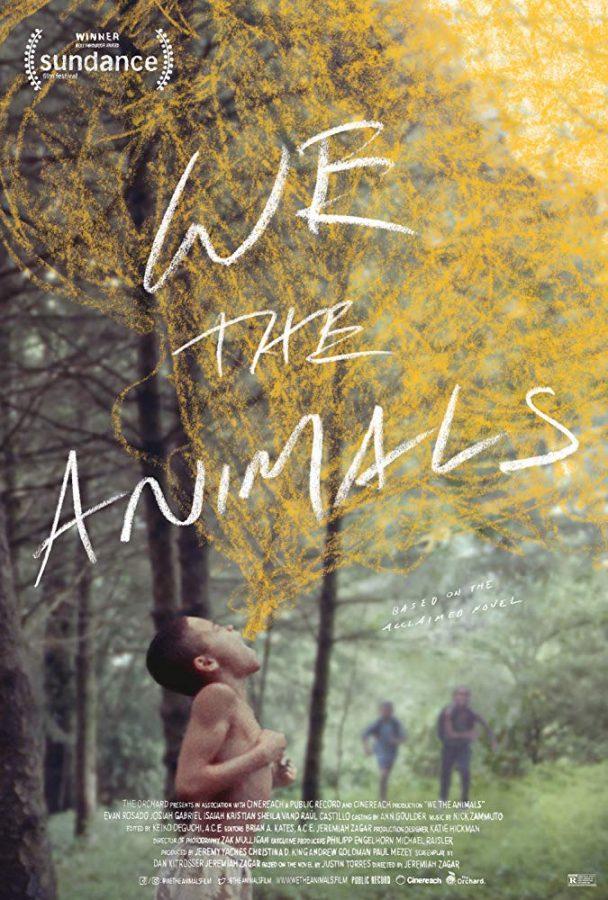

For the first few minutes of Jeremiah Zagar’s We the Animals, it is almost possible to believe that this film will be an idyllic foray into the bliss and beauty of childhood. Jonah (Evan Rosado) and his brothers Manny and Joel (Isaiah Kristian and Josiah Gabriel) frolic with youthful vibrancy through the sun-drenched fields and meadows of upstate New York. The movie is an aesthetic delight, with cinematographer Zak Mulligan using mostly 16-millimeter film to lend a hazy charm to the visuals of the venture.

However, Paps (played by Raul Castillo) soon offers his disruptive hand to the previously languid tone of the film; he forces Jonah to fend for himself in a river and provides the first real conflict of the movie. We see this dynamic further played out in Paps’ destructive relationship with his wife (dubbed ‘Ma’ by Jonah and played by Sheila Vand). The two struggle to make ends meet both in terms of finance and love — the two work blue-collar jobs that keep them away from the children for lengthy stretches. We only get glimpses of the couple’s tumultuous cycles through the mind of Jonah, who is unable to fully comprehend the abuse present between his parents. While too young to critically analyze the masculinity that his father portrays, Jonah does negatively respond to the paternal behaviors that his brothers begin to assume.

As a refuge from the insanity and neglect of his household, Jonah holes up with the grandson of his neighbor in their basement. Here, Jonah is exposed to Iron Maiden and his friend’s pornographic videos. This experience forces Jonah to consider his burgeoning sexuality outside of the oddities that he witnesses from his parents at home. It is noticeable that this exposure runs in such a contradicting manner to what he is directly observing in his family.

In order to grapple with all that is running through his young mind, Jonah turns to furious scribbles and illustrations in his secret journal. In the movie, these are visualized through abstract and abrasive animations of his musings. Here, crayoned stick figures fornicate and fight as Jonah attempts to make sense of what he is seeing. These moments are simultaneously exhilarating and confusing, as many of these images delve into some sort of dream world that Jonah has made up as the film goes along.

While the movie is visually stunning, the latter parts of the effort began to feel a little underwhelming as the runtime moves along. Zagar seems to rely too much on aesthetic and less on substance while much of the film’s imagery goes largely unexplained.

Reality and the universe that Jonah is imagining seem to be merging, but it is mostly unclear when this is happening and to what extent the illusion goes. Coupled with a lapse in character development, the final minutes of the movie seem to cram in as many awe-inspiring vistas as possible without reinforcing them with the weight of plausibility.

Gripes aside, this film is still a wonderful exploration of what it means to come into questions of identity when the odds are not stacked in one’s favor.