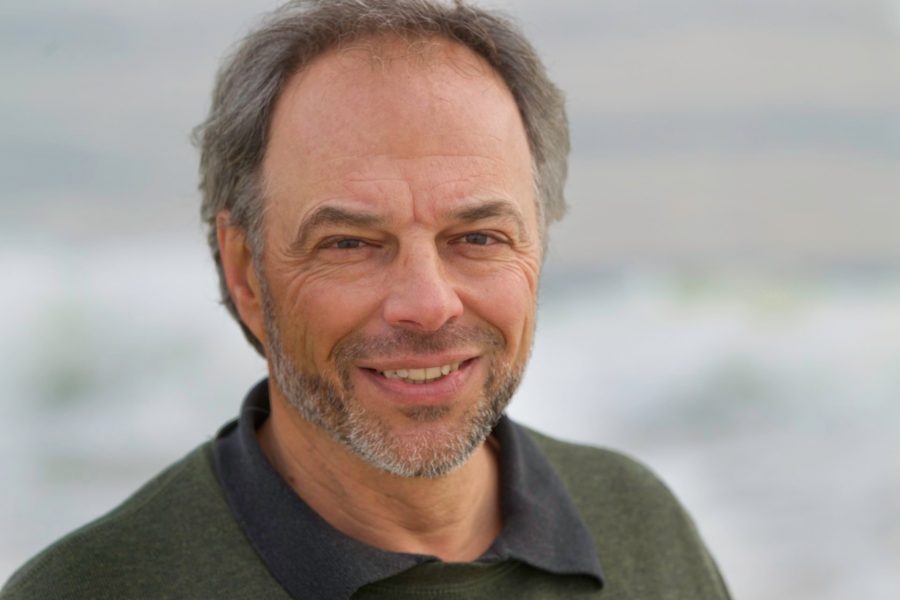

Last Wednesday, Stony Brook University professor of biology and author Carl Safina gave a public talk on his book Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel, one of seven books he wrote on animal ecology.

In addition to the public talk, Safina conducted a three-day writing workshop that taught students skills in both science and writing.

“I liked being able to talk on a personal level [with] Safina and learn of his experiences with writing and the natural world,” said Maggie Burns, a sophomore who participated in this workshop.

Safina’s public talk addressed the question of whether animals could feel emotions in a similar way to humans. He also suggested that humans do not appreciate the mental capacity and capabilities some animals have.

For example, an octopus is an extremely intelligent animal and its proficiency is often overlooked because it is a mollusk. Octopuses have brains as sophisticated as modern ape species, but many cultures around the world ignore this heightened intelligence and boil octopus as a seafood delicacy.

“There is a pattern that has been created,” said Safina. “There are capabilities in other animals that we don’t seem to appreciate until they hit a plate.”

In the past, there has been limited evidence that supports the capacity of animals to feel emotions and show empathy; however, this is changing due to current technology. Safina brought up a multitude of examples supporting the idea that animals have feelings, some technologically based and others supported through realworld experience.

One example Safina illustrated was how a human voice could provoke fear in elephants. Recordings were taken of people saying “Look, there’s an elephant” in English as well as in the Maasai language.

These recordings were placed in bushes where elephants could listen. The elephants were unfazed by the English recording, presumably because English is associated with harmless tourists. However, elephants were provoked with fear when they heard the Maasai recording because the elephants likely associated that sound to hunters and their spears.

Many undergraduate students were at the talk and seemed extremely interested in Safina’s examples.

“My favorite part of the [talk] was learning about wolves,” said sophomore Meredith Rasplicka. “I didn’t realize how close knit each pack was. When one family member was killed, it was amazing and devastating how the pack just crumbled apart.”

Safina mentioned that wolf packs are actually a nuclear family and that in fact, these animals need this type of atmosphere to successfully survive. He explained that there is a reason we have ancestors of wolves laying around our homes and not chimpanzees.

From a technological standpoint, Safina indicated that there are ways to show that animals react and have feelings; putting dogs into MRI machines is one example.

When the dog is put into the machine, it can be shown pictures of strangers and humans whom the dog loves. It has been supported by the MRI imaging that dogs’ brains lights up when seeing the loved one’s picture.

Safina also touched on the idea of what makes us human. He believes that animals and humans both have the ability to feel and show all of the same emotions, but humans have the unique ability to show emotion to extremes.

The human ability to have the “extremes” of feeling seems to have both positives and negatives. Safina observed that humans are often the most compassionate species, but also the cruelest.

“There was love on Earth before us, and there is love on Earth beside us,” said Safina.