Wake Forest was a different place when Allan Louden began teaching in 1977.

Louden, the chair of the communication department at the university, described a Wake Forest full of very young faculty, with few people tenured.

As the years went on, more of these young faculty earned tenure, and by the mid-90s almost two-thirds of faculty at the university were tenured.

“We were trying to become a national university,” Louden said. “It also probably has something to do with when they started raising tuition — they could afford new hires. These things have reasons at the time which have consequences later.”

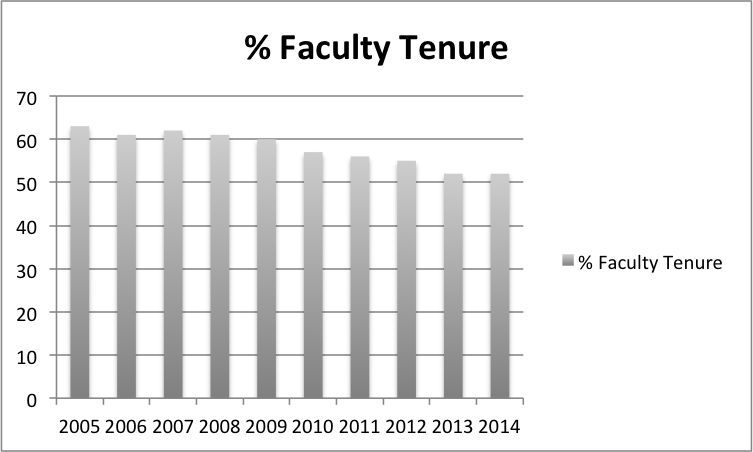

In 2014, 52 percent of all faculty were tenured, an 17.5 percent decrease from the 63 percent of faculty tenured in 2005. The number of tenured faculty had been at least 60 percent since 1990.

In comparison, about 33 percent of professors nationwide are tenured or on the tenure track, according to a report by the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges. This is a huge decrease from 1969, when 78.3 percent of all professors were tenured or on the tenure track.

However, this trend does not seem to apply at other top universities. At Princeton University, for example, the number of tenured faculty has stayed between 62 percent and 66 percent over the past 10 years. At the University of Richmond, 57 percent of faculty are tenured, and another 18 percent are on the tenure track.

“If you’re at [a good school], you stay. So there’s more retention. It also has to do with who they recruit in the first place, because they probably get good people, and there’s no reason for them to get bad over time,” Louden said. “The really good schools, and the private schools, are the ones that can typically afford to get good faculty and tenure them.”

There are roughly three categories of professors: tenure-track professors, teaching professionals and adjunct and visiting professors. In the majority of cases, the person applies for one of these three categories and sticks with it — it’s rare for someone who came into the university as a teaching professional to switch over to the tenure track.

The tenure track for professors is a six to seven-year process that involves yearly reviews, an analysis of classes the professor has taught, research he or she has done, course evaluations from students and external reviews of the professor’s research from outside experts in the subject.

Louden said there is a self-selection process to those who apply for tenure-track positions, similar to students who choose to apply to Wake Forest.

“People don’t come to Wake Forest [as students] and tend to get lazy. They go in the other direction,” he said. “Most people who are good enough to get tenure are pretty driven anyway. I can’t think of an instance where someone’s productivity was tied to their tenure.”

In response to worries about professor’s productivity levels, most people point to the benefits of tenure when used properly.

“Tenure has long been foremost a matter of academic freedom,” said Provost Rogan Kersh. “Because professors teach, create and write on all manner of topics, including views anathema to the mainstream and sometimes critical of the powerful, including university administrators, their liberty to pursue thoughts and scientific investigations wherever they may lead is of profound importance.”

Many professors also argue for the value of tenure.

“One value of tenure is stability for the institution. This allows departments and the whole university to commit to long-term goals that benefit students and society. Another is the freedom to pursue one’s research and scholarship as one chooses. A third is that tenure fosters attachment to the institution, which promotes selfless actions on the part of faculty, particularly in the area of service,” said Susan Fahrbach, chair of the biology department.

“It’s also important to note that the activities and accomplishments of all faculty in the college are reviewed every year, both at the departmental and college levels. So achieving tenure does not mean the end of performance evaluations — quite the opposite.”

Win-Chiat Lee, chair of the philosophy department, agrees that freedom is one of the most important features of faculty tenure.

“Academic freedom is the main justification for tenure, just as judiciary independence is the main justification for tenure in the case of federal judges. Academic freedom benefits both the faculty and the students,” Lee said. “Also, the university faculty is a self-governing body.

Without the independence protected by tenure, the duty of self-governance could not be properly discharged. There are downsides, but few. The costs are greatly outweighed by the benefits.”

Based on his experience, Louden also thinks professors generally become better teachers as they get older, not worse.

“They get markedly better for at least 10 years,” Louden said. “They know more, and they see more. They get more confidence and they know more stuff.”

Students had mixed feelings about tenured professors at the university.

“From my experience with professors who were granted tenure, I now have mixed feelings,” said senior Alex Irvine. “I had one professor who abused the power of tenure by not caring about our class anymore. I then had another professor who was such an intelligent, passionate and wonderful professor that she deserved tenure and continued to be a great professor even after she was on tenure status.”

To freshman Emily Sims, though, tenure is a great way to keep the best professors at Wake Forest.

“[Tenure] makes perfect sense,” Sims said. “I feel that tenure, if instilled to good standing professors, can be beneficial to the university because [the professors] can retain their jobs and would have to have good reason to be fired. If granted to a great professor, it means that he or she can continue to teach for a longer period of time.”