When the #MeToo movement formally started in early 2006, it focused on sexual harassment and assault among women around the globe, but it also opened a door for working professionals from all different backgrounds, disciplines and educational levels to express their dissatisfaction with the climate of gender inequality among their respective fields. Founded and formalized by Vanderbilt Professor BethAnn McLaughlin, the #MeTooSTEM movement provides a digital space for female scientists and mathematicians to share their experiences with gender disparity and harassment, while brainstorming ways to change it.

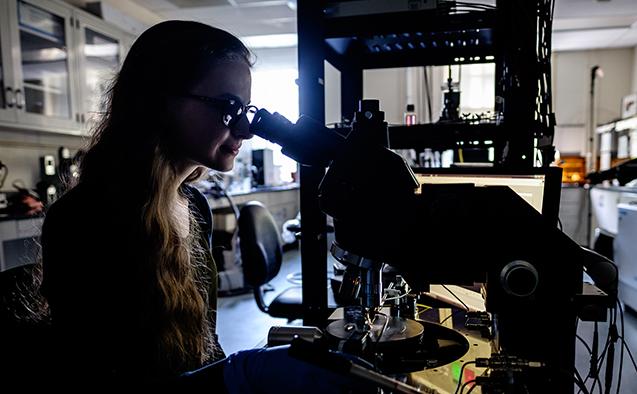

This virtual community touched the hearts and minds of accomplished women throughout the STEM field at all different professional levels, including Wake Forest Biology Professor Regina Cordy.

“A number of people on social media were raising concerns about gender and ethnic disparities in science,” Cordy said. “This eventually led a group of us young assistant professors to write a letter to the NIH [National Institutes of Health] to address the problem.”

Shortly after this group of professors voiced their concerns, the NIH listened.

In 2018, the NIH formed a working group on changing the culture to end sexual harassment, made up of professors, students, PhD candidates, provosts and Cordy.

The group is charged with identifying the current state of sexual harassment in the STEM field while determining steps that the NIH and other major scientific organizations can take towards improving the working environment for both men and women. They met once in Washington, D.C., this past February and discussed topics on accountability, providing clear channels of communication with the NIH and incorporating victims testimonials into future action.

Awareness and demand for change within STEM recently reached a turning point after the the National Academy of Sciences “Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine” report was published last year. Over 300 pages of data, diagrams and references to scientific literature statistically reinforced the presence of gender disparities within the STEM workplace and at universities.

“Scientists trusted this report more because it spoke their language in the form of data and statistics,” Cordy said.

Among other similar studies in the report, the University of Texas system conducted a survey which revealed that 20 percent of female science students, more than a quarter of female engineering students, and more than 40 percent of female medicals students experienced sexual harassment from faculty or staff. Many universities, including Wake Forest, are starting to crack down on gender inequality within STEM and are making strides towards improving learning environments, but still struggle in some aspects.

“I have been pretty lucky because the Wake Forest Department of Biology is a very inclusive space,” said Stephanie Bilodeau, a Masters student studying marine ecology. “But at times it is difficult to find women as mentors within my field because there are not enough female professors in ecology.”

The biology department has a relatively balanced staff of men and women, including a female department chair, but women in academia are typically warned of the difficulties of obtaining tenure and starting a family.

“You don’t think about it being weird until you have been here for two years and realize you have only been taught by male professors,” said Julia Haines, a senior with a double major in computer science and statistics.

A gender imbalance is not only recognizable among professors in certain faculties, but in the student STEM community, as well. Particularly in the math department, apart from statistics, there is a wide gap between the number of male and female undergraduate majors, with few females enrolled in into upper-level classes each year.

“Growing up in small-town Georgia I had to fight to get into math classes because it was just accepted that the boys would fill them,” said Camille Wixon, a senior math and economics double major.

In her economics classes, Wixon noted how vocal the professors are about wanting more female majors, but data has shown that only 35 percemt of undergraduate economics majors are women, a number that has barely increased since the early 1980s according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. So, the question that many educators and scientists are asking is: how do we fix this?

One of the major problems many students recognized is that women are struggling to find enough female mentors within the field as they work to pursue a STEM career. Without seeing a model of what could happen for a female if she continues with a scientific education, some students lack the ambition or optimism to attempt to achieve a higher position in these careers.

However, clubs on campus like Women in STEM are working hard to provide this mentorship to the next generation. Members of this club visit students at Northwest Middle School in Winston-Salem to show them that studying STEM in higher education is possible for women.

“A lot of rhetoric is thrown around like ‘I like science, but I don’t think I could get there’ or ‘I am not smart enough,’” said Yassmin Shaltout, a junior and president of the Women in STEM club. “We teach them science lessons that are fun and interactive to maintain interest in these younger females.”

The two main goals of this club, and many organizations throughout the United States and Europe, are raising awareness of the problem and providing outreach to help solve it. Although the formalized movement against sexual harassment and gender disparities is relatively new in the STEM field, it is gaining traction within organizations like the NIH that have a wide reach and enough resources to make an impact.

“Women are here. They are doing science. And they are awesome at it,” Shaltout said.