The film Underwater is a middle-finger-to-the-man placed under the sea, with a rebelliousness more jagged than the any slick pseudo-politics its involves. It’s more rich, eschatological fantasy than boring memorandum. At times notably vivid and well-framed, Underwater satisfies its sci-fi/horror billing, gently echoing canon (usual suspects like The Thing, Alien) in a tight 95-minute clip. The film stars Kristen Stewart, which is pretty much all you need (and most of what you get), though Underwater’s commitment to genre means it’s also peopled with light and retractable stock characters. So while the film layers in tropes, and surprises us with some sophisticated camerawork and striking compositions, it anchors itself in the magnetism of Stewart who, though maybe working slightly below her pay grade, reminds us that she alone turned shy talking into importunate genius. Stewart sometimes humanizes her lines too much, especially for a film about sea monsters.

Narrated in her least-garrulous way, Stewart’s voice, unlike Brad Pitt’s, whose tedious narration of Ad Astra bloated the film badly, filigrees Underwater with aphoristic spunk. It’s a welcome respite from the film’s otherwise breakneck speed (even underwater, where figures move with forced languor, we are pushed up inside helmets enough to make Underwater feel like a space movie). The Kepler station, where Stewart’s Norah works as a mechanical engineer, is the world’s deepest drill. We are told through news clippings, running under the opening credits, that the project is steeped in an environment so deep its surrounding perils remain unknown. Within five-minutes of Underwater, a large portion of the workplace blows, and we are taken on a beautifully focused scramble, cameras following with a grip akin to a Crank action sequence. Norah is immediately competent and relatively calm, although her compassion for the numbered dead stalls some of her decisiveness. As she moves through the wreckage, we move through swift introductions that assemble the film’s traveling cohort. Emily (Jessica Henwick), a bright, young researcher and nervous chatter, Smith (John Gallagher Jr.), her co-worker and love-interest, Paul (TJ Miller in a satisfying gallows humor role) and self-sacrificing “Captain” as he’s only named (Vincent Cassel, allowed to keep his accent) populate the film as various human expiration dates.

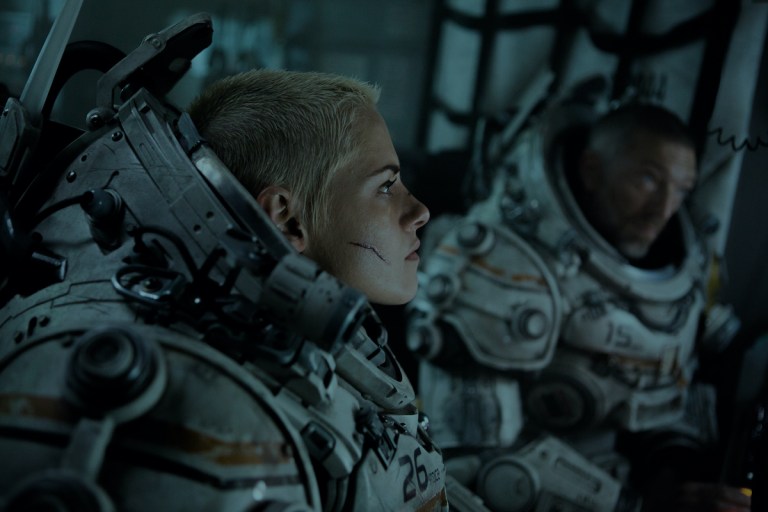

Photo courtesy of imdb.com

Norah (Kristen Stewart) earnestly discusses plans for the wellbeing of the engineering crew with Emily (Jessica Henwick), Smith (John Gallagher Jr.) and Captain (Vincent Cassel).

So, what caused the explosion? Based on the visuals, some lumbering Godzilla-Poseidon amalgam pissed off about the neighbors, who also has heat-seeking lackeys attached to its skin that pick off the crew one by one. Underwater is one of those films where you can guess the order in which people perish — and when — but that’s ok. It is heady for other reasons, namely Stewart, cinematographer Bojan Bazelli and director William Euback, who hasn’t directed much, but has fourteen cinematography credits to his name. Less a visual bonanza than a submerged and subdued Niconlas Winding Refn film, Underwater’s visuals disappear for stretches, which makes ignition-by-Kristen (the most striking compositions contain only her) doubly noticeable. Plus, with its short run time, Underwater has no time to filibuster, which means characters speak their lines and briskly exit, nodding to the genre as they go. Allowed to commit to pace and vision (and Stewart), Eubank makes the film feel like a torpedo chasing its explosion.

We tend to give directors a film’s possessive: a Martin Scorsese picture, Spike Lee joint, etc. But even Eubank knows Underwater, without Stewart as anchor and universe unto herself, doesn’t have a pulse, and dies, unseen, as genre fodder. Without Stewart’s unique command, Underwater becomes amnesia. I don’t mean to be blithe, but Stewart really does recue this film from anonymity (“ah, yes, the new Kristen Stewart underwater movie”), and in doing so, hopefully makes viewers notice its other virtues. It’s widely-known that once a director bolts star-power onto a film, the project stands a chance of making money. And that is true for Underwater, though I’m talking about a greater return. A rare actor can simultaneously draw attention to themselves and to their medium, emanating a personal light that draws in technical beauty. At least in Underwater, Stewart makes the creativity invested in a film seem (almost) adequate to its actor. Her Beat-intensity and charged, velvet voice bleed into the film’s musculature. Stewart’s depth drips highlighter onto the film reel, raising all the film’s hidden achievements to the surface, and one trusts if Stewart picked the project, the result must contain as much talent as she does. It doesn’t, but she makes it acceptable to think so. And even still, it must be said, there are a few itchy moments where it’s clear Stewart belongs back upstairs. But with a completely forgettable script, Stewart’s delivery makes the sci-fi shoptalk and narrative philosophy sound either warranted or committed or (dare I say) meaningful.

I saw the run time of Underwater and immediately decided to see it. After a holiday season of great films all at-or-over two-hours-and-fifteen minutes, plus with Magnolia streaming on Netflix again, I craved an in-and-out that could also satisfy. But there’s hardly such a thing as brevity anymore in the theater. Even bad films are too long. Quick rides that tattoo us with memorable stories are difficult to find. Mostly, they’re first-feature anomalies like Lady Bird. Now, Underwater is a far cry from Lady Bird, but it’s at least tight. And has a few virtues. And has Kristen Stewart.